Non-Shared Environment Doesn’t Just Mean Schools And Peers

[Epistemic status: uncertain. Everything in here seems right, but I haven’t heard other people/experts in the field talk about this nearly as much as I would expect them to if it were true. Obviously amount of variability attributable to environment (shared and non-shared) increases as the variability in environments in the sample increases]

The “nature vs. nurture” question is frequently investigated by twin studies, which separate interpersonal variation into three baskets: heritable, shared environmental, and non-shared environmental. Heritable mostly means genes. Shared environmental means anything that two twins have in common – usually parents, siblings, household, and neighborhood. Non-shared environmental is everything else.

At least in relatively homogeneous samples (eg not split among the very rich and the very poor) studies of many different traits tend to find that ~50% of the variation is heritable and ~50% is due to non-shared environment, with the contribution of shared environment usually lower and often negligible. This is typically summarized as “50% nature, 50% nurture”. That summary is wrong.

I mean, it’s tempting. All these social developmentalists were so sure that the way your parents praised you or didn’t praise you, or spanked you or didn’t spank you, had long-lasting repercussions that totally shaped your adult personality. The underwhelming performance of shared environment in twin studies torpedoed that whole area of study. But at least (these scholars of social behavior could tell themselves) it provided a consolation prize. The non-shared environment contributes 50% of variation, just as much as genes. That means things like your friends, your schoolteachers, and even that time you and your twin got sent away to separate camps must be really important. More than enough there to continue worrying about how society is Ruining The Children, right?

Not necessarily. Non-shared environment isn’t really “non-shared environment” the way you would think. It’s more of a dumpster. Anything that isn’t genetic or family-related gets tossed into the non-shared environment term. Here are some of the things that go into that 50% non-shared environment:

1. Error. Measurement error is neither genetics nor family, so it ends up in the non-shared environmental term. Suppose you’re studying intelligence, and you make a bunch of twins take IQ tests. IQ tests measure intelligence, but not perfectly. For example, someone who makes a lucky guess on a multiple choice IQ test will get a higher score even though they are not more intelligent than someone who makes an unlucky guess. Someone who takes the test when they’re tired and stressed may get a lower score even though they’re no less intelligent than somebody else who takes it well-rested and feeling good.

Imagine a world where intelligence is entirely genetic. Two identical twins take an IQ test, one makes some lucky guesses, the other is tired, and they end up with a score difference of 5 points. Then some random unrelated people take the test and they get the 5 point difference plus an extra 20 point difference from genuinely having different IQs. In this world, scientists might conclude that about 80% of IQ is genetic and 20% is environmental. But in fact in terms of real, stable IQ differences, 100% would be genetic and 0% environmental.

This gets even harder when trying to measure fuzzier constructs like criminality. Suppose someone does a twin study on criminality and their outcome is whether a twin was ever convicted of a felony. This depends partly on whether the twin is actually the sort of person with criminal tendencies – but also partly on whether a policeman happened to be in the area to catch them, whether their lawyer happened to be good enough to get them off, whether their judge was feeling merciful that day, et cetera. Imagine a world where criminality is entirely genetic. Identical Twin A becomes a small-time cocaine dealer in a back alley in West Philly, sells to an undercover cop, and ends up in jail. Identical Twin B becomes a small-time cocaine dealer in a back alley in East Philly, doesn’t run into any undercover cops, and so avoids conviction. This shows up as “variation in criminality is due to non-shared environment”.

Riemann and Kandler (h/t JayMan) run a study which is an excellent demonstration of this. Classical twin studies sometimes use self-report to determine personality – ie they ask people to rate how extraverted/conscientious/whatever they are. These studies find that most personality traits are about 40% genetic, 60% non-shared environmental. Riemann and Kandler obsessively collect every possible measurement of personality – self-report, other-report, multiple different tests – and average them out to get an unusually accurate and low-noise estimate of the personality of the twins in their study. They find that variation in personality is about 85% genetic, 15% non-shared environmental. So it looks like much of the non-shared environmental variation in traditional studies of personality was just error.

2. Luck of the draw. Bob becomes a junior advertising executive at Coca-Cola, where he designs a new ad targeting young female consumers. His identical twin Rob becomes a junior advertising executive at Pepsi-Cola, where he designs his own new ad targeting young female consumers. Both ads are very successful – in fact, exactly equally successful. But Coke’s CEO is a crony capitalist who wants to replace everyone in the company with his college buddies, so he ignores Bob’s good work and demotes him to a low-level position. Pepsi’s CEO is a skilled leader who recognizes good talent when she sees it, and she promotes Rob to Vice-President Of Advertising.

Now a scientist comes along, does a twin study on them, and finds that they have very different levels of income. She reports that there’s a lot of difference between these two identical twins, so much of income must be non-shared environmental.

Science reporters read the study finding that much of the variation in income is non-shared environmental, and conclude that despite their identical genes, there must be deep and mysterious differences in Bob and Rob’s abilities and business acumen. They speculate that Rob had a very inspirational teacher in school who pushed him to achieve greatness, and Bob must have fallen in with a bad peer group who didn’t value hard work.

But actually, Bob and Rob are completely identical in every way, no incident in their past did anything to separate them, and Bob just ended up working for a crappy CEO. In this scenario, inherent predisposition to earning money is exactly the same in both twins, they just have different amounts of luck at it. If both twins become pathological gamblers, but one of them hits the jackpot and the other goes broke, that will show up as “non-shared environment” too.

3a. Biological random noise. The genome can’t encode the location of every cell in the body. Instead, it specifies high-level processes which create lower-level processes which create those cells. But this gives the lower-level processes a lot of leeway, meaning that there can be significant biological differences between identical twins.

Consider by analogy The Postmodernism Generator. It’s a cute program that will make a (sort of) convincing sounding postmodernist essay on demand. We can imagine hundreds of different programmers all designing their own postmodernism generators. Some would be really brilliantly designed and consistently come up with plausible looking essays. Others would be poorly designed and consistently come up with crappy essays that don’t convince anybody. But there would also be variation within the results of each generator. There might be a generator that is mostly terrible but occasionally by coincidence comes up with a really funny essay, or vice versa. In this analogy, the genes are the code for the generator, and the person is an individual essay produced by that generator.

Thus, identical twins have different fingerprints, different freckles, and different birthmarks. Only about a fifth of left-handers’ identical twins will also be left-handed. And twins even look different enough that their friends and parents eventually learn to tell them apart. All of these are non-genetic issues likely to show up in “non-shared environment” but not related to schools or peers or “nurture” as traditionally conceived.

3b. The immune system. Immunology is still poorly understood, but it seems very important. Immune reactions and neuroinflammation have been implicated to one degree or another in a lot of psychiatric diseases. A functional immune system can protect good health; a dysfunctional immune system can make someone constantly tired and miserable.

There seems to be more of an element of chance to the immune system than to a lot of other bodily processes. Part of it is the input – one child in a twin pair might inhale a particle of cat dander at a critical time; another might get some unknown adenovirus with no immediate effects but which contributes to obesity twenty years later. Another part is the output; sometimes a natural killer cell stumbles across something quickly and takes it out without any fuss; other times the immune system misses it for a while and it gets more of a chance to spread.

The end result is that immune-system-related-conditions are really discordant across identical twins. If your identical twin has asthma, there’s only a 33% chance you’ll have it as well. If your identical twin has Crohn’s disease, a disabling autoimmune intestinal condition, there’s only a 50% chance you’ll suffer the same. I’m not sure how significant this is in the broad scheme of things, but I suspect more so than people think.

3c. Epigenetics We know that identical twins have substantially different epigenetics, and there are hints that this underlies discordant behavior. This is probably really important, but I feel bad bringing it up because it seems to be passing the buck. We usually think of epigenetic differences as a response to different environments or life choices. But if identical twins start with the same environment and can be expected to make the same life choices, why do they end up with different epigenomes? I’m not sure what to do with this one.

3d. Genes that differ between identical twins. Apparently this happens! Identical twins come from the same zygote, which means they start out with the same genes, but after that all bets are off. If there’s a mutation in one twin in the first embryonic division, then half of that twin’s cells will carry that mutation. Remember that there are a lot of divisions and opportunities for mutation before any cells even start forming the brain, and any mutation before that time could be transmitted to all brain cells. One study found that the average identical twin pair probably has about 359 genetic differences occuring early in development.

I’ve grouped 3a, 3b, 3c, and 3d together as possible biological sources of variation. One of these – or maybe some 3e I don’t know about – is probably the reason for less-than-perfect twin concordance in conditions like Parkinson’s disease, migraine, autism, and schizophrenia. Needless to say, anything that can make you schizophrenic can probably affect your personality and life outcomes pretty intensely.

But all of this gets counted as “non-shared environment” in a twin study, and used to play up the importance of schools and peer groups.

4. Actual nurture. Twins do have different experiences growing up. How much does this shape their adult traits? Can we separate this out in to specific experiences that shape adult traits, like school and summer camp?

The good news is that Eric Turkheimer has a big review article on this; the bad news is that the discussion section is called “The Gloomy Prospect” and says:

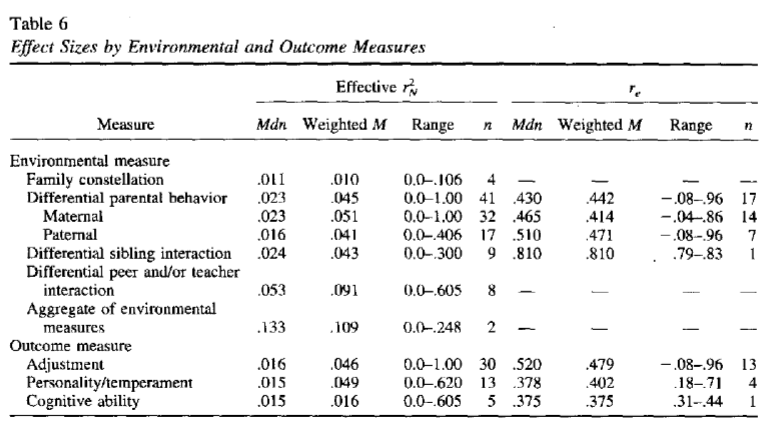

Quantitative analysis of studies of specific nonshared environmental events shows that effect sizes measuring the effects of such variables on child outcomes are generally very small. Effect sizes are largest when confounds with genetic variability and outcome-to-environment causal effects are not controlled. When such confounds are controlled, as in the most recent reports from the NEAD project, effect sizes become smaller still.

I’m not sure if this table represents the “very small” uncontrolled or the “smaller still” controlled sizesThe paper concludes: “We emphasize that these findings should not lead the reader to conclude that the nonshared environment is not as important as had been thought.”

But although I have a huge amount of respect for Turkheimer, I kind of want to conclude that the nonshared environment is not as important as had been thought. My guess is that the nonshared environment as Turkheimer discusses it – differential parenting, schools, peers, and so on – is only a fraction of the “nonshared environmental” term in genetics studies.

If that were true, it would mean that nature is more important than we thought relative to environment in terms of things we can understand and possibly affect. That would make the quest to change important outcomes like intelligence, personality, income, or criminality by changing society even more daunting. And it would make the opportunity to change those outcomes through genetic engineering even more tempting.