Some Antibiotic Stagnation

In the past week I’ve written about antibiotics and the rate of technological progress. So when a graph about using antibiotics to measure the rate of scientific progress starts going around the Internet, I take note.

Unfortunately, it’s inexcusably terrible. Whoever wrote it either had zero knowledge of medicine, or was pursuing some weird agenda I can’t figure out.

Unfortunately, it’s inexcusably terrible. Whoever wrote it either had zero knowledge of medicine, or was pursuing some weird agenda I can’t figure out.

For example, several of the drugs listed are not antibiotics at all. Tacrolimus and cyclosporin are both immunosuppressants (please don’t take tacrolimus because you have a bacterial infection). Lovastatin lowers cholesterol. Bialafos is a herbicide with as far as I can tell no medical uses.

“Cephalosporin” is not the name of a drug. It is the name of a class of drugs, of which there are over sixty. In other words, the number of antibiotics covered by that one word “cephalosporin” is greater than the total number of antibiotics listed on the chart.

If I wanted to be charitable, I would say maybe they are counting similar medications together in order to avoid giving decades credit for producing a bunch of “me-too” drugs. But that doesn’t seem to be it at all. They triple-count tetracycline, oxytetracycline, and chlortetracycline, even though they are chemically very similar and even though the latter are almost never used (the only indication Wikipedia gives for the last of these is that it is “commonly used to treat conjunctivitis in cats”)

They also leave out some very important antibiotics. For example, levofloxacin is a mainstay of modern pneumonia treatment and the eighth most commonly used antibiotic in the modern market. That’s a whole lot more relevant than cats with pinkeye, but it is conspicuously missing while chlortetracycline is conspicuously present. Maybe it has something to do with levofloxacin being approved in 1993?

(also missing from the 90s and 00s: piperacillin, tazobactam, daptomycin, linezolid, and several new cephalosporins)

I can’t find a real table of antibiotic discovery per decade, so I decided to make some.

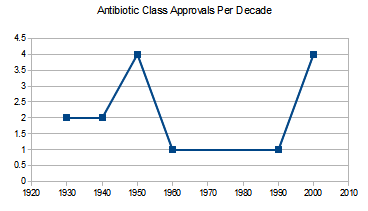

Antibiotic classes approved per decade. An antibiotic class is a large group of drugs sharing a single mechanism. For example, penicillin and methylpenicillin are in the same class, because one is just a slight variation on the chemical structure of the other. There are some arguments over which new drugs count as a “new class”. Source is this source.

Antibiotic classes approved per decade. An antibiotic class is a large group of drugs sharing a single mechanism. For example, penicillin and methylpenicillin are in the same class, because one is just a slight variation on the chemical structure of the other. There are some arguments over which new drugs count as a “new class”. Source is this source.

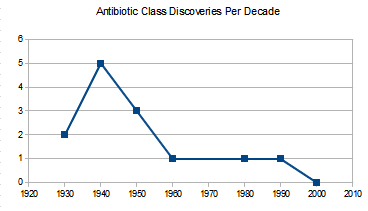

Anbiotic classes discovered per decade. The first graph lists when classes got FDA approval, this one lists when they were first discovered. Both have different pluses and minuses. This one is likely to undercount recent progress because the chemicals being discovered now haven’t been tested and found to be valuable antibiotics and approved (and so don’t make it onto the graph). But the last one might overcount recent progress, because a drug being “approved” in 2010 might represent the output of 1980s science that just took forever to get through the FDA. On the other hand, it might not – a lot of times people find a drug class in 1980, decide it’s too dangerous, and only find a safer useable drug from the same class in 2010.

Anbiotic classes discovered per decade. The first graph lists when classes got FDA approval, this one lists when they were first discovered. Both have different pluses and minuses. This one is likely to undercount recent progress because the chemicals being discovered now haven’t been tested and found to be valuable antibiotics and approved (and so don’t make it onto the graph). But the last one might overcount recent progress, because a drug being “approved” in 2010 might represent the output of 1980s science that just took forever to get through the FDA. On the other hand, it might not – a lot of times people find a drug class in 1980, decide it’s too dangerous, and only find a safer useable drug from the same class in 2010.

Individual antibiotics discovered per decade. Individual antibiotics can still be vast improvements upon previous drugs in the same class. Source is here. I have doubled the number for the 2010s to represent the decade only being half over and so make comparison easier. About half of that spike around 1980 is twenty different cephalosporins coming on the market around the same time.

Individual antibiotics discovered per decade. Individual antibiotics can still be vast improvements upon previous drugs in the same class. Source is here. I have doubled the number for the 2010s to represent the decade only being half over and so make comparison easier. About half of that spike around 1980 is twenty different cephalosporins coming on the market around the same time.

I conclude that antibiotic discovery has indeed declined, though not as much as the first graph tried to suggest, and it may or may not be starting to pick back up again.

Two very intelligent opinions on the cause of the decline. First, from a professor at UCLA School of Medicine:

There are three principal causes of the antibiotic market failure. The first is scientific: the low-hanging fruit have been plucked. Drug screens for new antibiotics tend to re-discover the same lead compounds over and over again. There have been more than 100 antibacterial agents developed for use in humans in the U.S. since sulfonamides. Each new generation that has come to us has raised the bar for what is necessary to discover and develop the next generation. Thus, discovery and development of antibiotics has become scientifically more complex, more expensive, and more time consuming over time. The second cause is economic: antibiotics represent a poor return on investment relative to other classes of drugs. The third cause is regulatory: the pathways to antibiotic approval through the U.S. FDA have become confusing, generally infeasible, and questionably relevant to patients and providers over the past decade.

A particularly good example of poor regulation from the same source:

When anti-hypertensive drugs are approved, they are not approved to treat hypertension of the lung, or hypertension of the kidney. They are approved to treat hypertension. When antifungals are approved, they are approved to treat “invasive aspergillosis,” or “invasive candidiasis.” Not so for antibacterials, which the FDA continues to approve based on disease state one at a time (pneumonia, urinary tract infection, etc.) rather than based on the organisms the antibiotic is designed to kill. Thus, companies spend $100 million for a phase III program and as a result capture as an indication only one slice of the pie.

And one more voice, which I think of as a call for moderation. This is Nature Reviews Drug Discovery:

Most antibiotics were originally isolated by screening soil-derived actinomycetes during the golden era of antibiotic discovery in the 1940s to 1960s. However, diminishing returns from this discovery platform led to its collapse, and efforts to create a new platform based on target-focused screening of large libraries of synthetic compounds failed, in part owing to the lack of penetration of such compounds through the bacterial envelope.

Sometimes stagnant science means your civilization is collapsing. Other times it just means you’ve run out of soil bacteria.

In a way, this points out the unfairness of using antibiotics as a civilizational barometer. This is a drug class first invented in the 1930s and mostly developed by investigating soil bacteria, which have since been mostly exhausted. Of course progress will be faster the closer to the discovery of this technique you get.

If instead you use antidiabetic drugs – a comparatively new field – this is an age of miracles and wonders, with new classes coming out faster than anyone except specialists can keep up with. If antidiabetic drugs were used as a civilizational barometer, we would be having the Singularity next week.