SSC Journal Club: Mental Disorders As Networks

I.

Suppose you have sniffles, fatigue, muscle aches, and headache. You go to the doctor, who diagnoses you with influenza and gives you some Tamiflu.

There’s some complicated statistics going on here. Your doctor has noticed some observable variables (sniffles, fatigue, etc) – and inferred the presence of an invisible latent variable (influenza). Then, instead of treating the symptoms with eg aspirin for the headache, she treats the latent variable itself, expecting its effects to disappear along with it.

Psychiatry tries to use the same model. You get some symptoms – depressed mood, insomnia, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness, suicidality. You go to the psychiatrist, who diagnoses you with depression and gives you an antidepressant.

The psychiatrist is implicitly assuming that the causal structure of her field matches the causal structure of better-understood diseases like influenza. Generations of psychiatrists have noticed that different symptoms all tend to show up together and follow a similar pattern, suggesting some kind of deep connection between them. So psychiatrists follow the influenza model and attribute this collection of linked symptoms to a latent variable called “depression”.

This gets complicated really fast. Psychiatric disorders are diagnosed through clusters of symptoms, but we don’t expect every person to have every symptom in the cluster. For example, we diagnose depression when a patient has five out of nine symptoms on a list including fatigue, guilt, sleep disturbance, suicidality, et cetera. Each of these symptoms is often but not always present in a patient who has most of the others – for example, 75% of depressed patients have sleep disturbances, but 25% don’t.

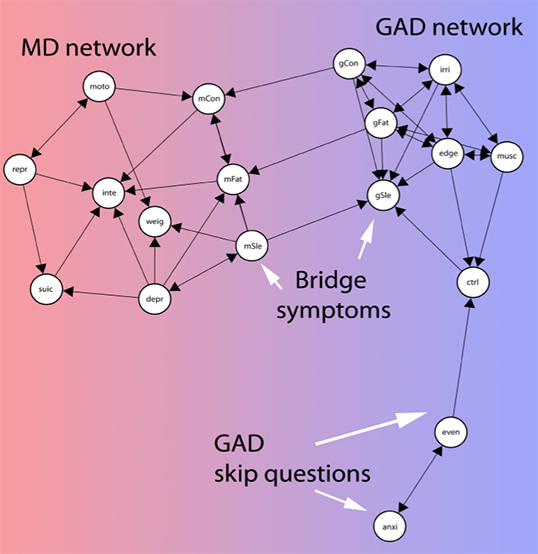

But all psychiatric disorders are hopelessly comorbid with each other. If someone meets criteria for one DSM disorder, there’s a 50% chance they’ll have another one too. 60% of people with major depression also have an anxiety disorder. This is awkward when compared to eg the 75% sleep disturbance rate. Why are we calling sleep disturbance a “symptom” of depression, but anxiety a “comorbid condition” with depression? If we’re trying to cluster symptoms together to identify conditions, how come “sleep” is grouped with a bunch of other symptoms in the depression cluster, but “anxiety” gets to be a cluster of its own? Are there really two conditions called “depression” and “anxiety”, or just one big condition that has various symptoms including low mood, sleep disturbance, and anxiety, and some people get some of the symptoms and other people get others? I’m told that the people who write the DSM have long conversations about this using rigorous methods, but to the rest of us it seems kind of arbitrary.

The problem isn’t that nothing ever clusters together – depression, for example, is a very natural category. But so are various subtypes of depression. And so are various supertypes of depression, like depression + anxiety, or depression + psychosis, or depression + anxiety + psychosis. Choosing to draw the borders around depression and say “Yup, this is the Actual Disease” isn’t a bad choice, but it doesn’t jump out of the data either. When people try to use sophisticated clustering algorithms on psychiatric disorders, they usually come up with something like this, where there are only three supercategories instead of the 297 different diagnoses in the DSM. And even three supercategories are pushing it – people with psychosis are far more likely to have depression too! Having any number of categories starts seeming arbitrary and fuzzy.

So Nuijten, Deserno, Cramer, and Borsboom (from here on: NDCB) ask: what if that’s wrong? What if there isn’t a latent variable like “influenza”? What if it’s symptoms all the way down?

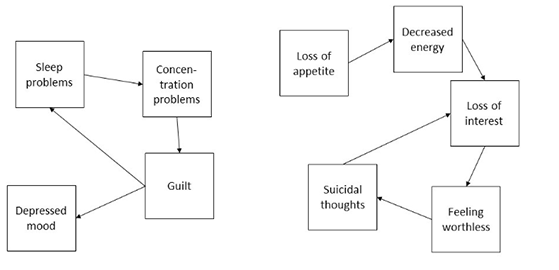

Consider a network in which each symptom is a node, connected to all the others by pathways with certain weights on each direction. So for example, “sleep disturbance” might be connected to “fatigue” by a strong path – people with disturbed sleep are much more likely to be tired. These might both be connected to “low mood” – people who don’t sleep well, or who are tired all the time, start feeling down about themselves. And this path might go the other way too: people who feel down about themselves might have more trouble getting to sleep on time. And maybe all of these are connected to suicidality, because if you feel bad about yourself you’re more likely to commit suicide, and if you’re suicidal you might feel bad about it, and if you’re tired all the time then maybe you can’t accomplish anything useful with your life and so death might seem like a good way out, and so on.

A sample image from the paper, showing two possible simple networks of depression symptoms

A sample image from the paper, showing two possible simple networks of depression symptoms

Also from the paper. This shows a more complicated (and apparently empirically validated) network of symptoms. MD is major depression. GAD is generalized anxiety disorder. The nodes are all different symptoms – for example, “inte” is “loss of interest in activities” and “musc” is “muscle tension”.

Not from the paper. But if you figure out a good way to calculate weights on this one, email me.

Each node might affect the others with a certain delay. Being suicidal might make you feel guilty, but even if your last suicidal thought was fifteen minutes ago, you might still feel guilty now. Maybe it would take months or even years before you no longer felt guilty about your suicidal thoughts. So there could be loops: in a simple model, your low mood makes you feel suicidal, your suicidality makes you feel guilty, and your guilt makes you have low mood. This type of loopy network might be stable and self-reinforcing. Maybe your boss yells at you at work, which makes you have a bad mood. Then even if the direct effect of your boss would go away quickly, if it causes suicidal thoughts which cause guilt which cause more low mood, then the cycle can stick around forever.

In NDCB’s model, all possible psychiatric symptoms are connected like this in a loose network. Particularly tight-knit symptom clusters that often active together and reinforce each other correspond to the well-known and well-delineated psychiatric diseases, like depression and schizophrenia. But there are no natural boundaries in the network; low mood and poor sleep may be closely connected to each other, but they’ll also be more distantly connected to anxiety, and even more distantly connected to psychosis. This corresponds to the fact that some depressed people will develop psychotic symptoms, even though psychosis isn’t usually associated with depression. The paths aren’t usually as strong as those between low mood and poor sleep, but they’re there, and in some people with a predisposition to psychosis or some idiosyncratic factor strengthening those paths beyond their usual level in the population, that will be enough.

There are lots of good things about thinking about psychiatric problems this way:

1. It helps explain how life stressors can cause depression. Some people who have a bad breakup will get depressed. This should be mysterious if we think of depression as a biological illness – and we have to at least a little; some people who take the drug interferon-alpha will get depressed afterwards too. But if depression is a symptom network, it becomes easier to explain. The bad breakup causes low mood, which under the right conditions and genetic predispositions can activate all of the other depression symptoms and create a stable, self-reinforcing depression. Likewise, poor sleep is a risk factor for the development of subsequent depression, which is hard to explain if we just think of it as a symptom of some latent-variable-style condition.

2. It explains how treating depression symptoms can treat the depression. I’ve heard a lot of different perspectives on this, but at least one of my attendings (and some studies) believes that treating poor sleep with a sleeping pill like Ambien can help dispel an underlying depression, including symptoms seemingly unrelated to sleep like “feelings of worthlessness and guilt”.

3. It explains how therapy can treat depression. If eg cognitive behavioral therapy helps you stop thinking of yourself as worthless, then you’ve de-activated the “feelings of worthlessness and guilt” node and made it a lot harder for all the other nodes to coalesce into a stable self-reinforcing pattern.

4. It explains the polygenic structure of mental illnesses. If a mental illness were one specific thing, we would expect it to have one specific cause, or at least be limited to genes active in one specific area or process. In fact, it’s hard to come up with anything that genes involved in these illnesses have in common other than “they’re mostly expressed in the brain” – and sometimes not even that. In NDBC’s model, genes might be involved in any of the symptoms, or in the paths between the symptoms. A gene involved in poor sleep could predispose to depression. So could a gene involved in low energy levels. Even a gene involved in anxiety or psychosis could have some effect. And so would any gene that influenced the probability that, given poor sleep, a person would have low energy levels; or that given anxiety, a person will have psychosis. The end result would be everyone having a slightly different network, with different amounts of work needed to activate each node and different weights on each of the inter-nodal paths.

5. It helps explain why so many brilliant people searching for The One True Cause Of Depression have come up empty.

II.

Actually, this last one deserves more explanation. NDCB think of these symptoms as visible patient complaints (“poor sleep”, “feelings of worthlessness”), and treat the connections between them as common sense (“if you don’t sleep, you’ll probably be fatigued”, “if you feel very guilty, you might attempt suicide because you think you deserve to die”). But their theory also works for networks of biological dysfunctions, or networks that combine biological dysfunctions with common-sense observed symptoms.

For example, we know that there’s a link between depression and inflammation. But it’s not a very good link; not all depressed people have increased inflammation, not all people with increased inflammation get depressed, and drugs that decrease inflammation don’t always cure depression. There’s similarly good evidence linking depression to folate metabolism, serotonergic neurotransmission, BDNF levels, and so on. Suppose we made a graph like the ones above, except that instead of putting things like “poor sleep” and “feelings of guilt” on it, we used “inflammatory dysfunction”, “folate metabolism dysfunction”, “serotonin dysfunction”, and “BDNF dysfunction”. There are a lot of reasons to expect these things to interconnect – for example, folate helps produce a cofactor necessary for serotonin synthesis, so any dysfunction in folate metabolism could make a problem with serotonergic neurotransmission more likely.

In a best case scenario we could merge the biological and psychological perspective, replacing “disturbed sleep” with “disturbance in the orexin and histamine systems that regulate sleep” and “tiredness” with “disturbance in the dopamine system that regulates goal-directed action”, and so “poor sleep makes you tired” with “disturbance in the orexin system causes a disturbance in the dopamine system”. In practice I expect this would be a terrible idea and that common-sense concepts mostly don’t have simple well-delineated biological equivalents. But what I’m saying is that the model where all of these things are observable symptoms, and the model where they’re all disturbances in brain chemicals and metabolism, aren’t necessarily in conflict.

So we can expand point (5) to say not only that it explains why nobody has found the One True Depression Cause, but why they have found so many promising leads that never quite pan out. Just like depression has a bunch of different symptoms, each of which is often-but-not-always involved, and each of which reinforces the others — so it has a bunch of different disturbances in biological systems, each of which is often-but-not-always involved, and each of which reinforces the others. Maybe there’s a nice correspondence between one disrupted biological system and one symptom, or maybe they sit uneasily together as different nodes on the same big graph.

III.

Are there any problems with this theory?

There are a couple of disorders that really don’t fit this model. Bipolar disorder, for example, doesn’t quite work as a collection of self-reinforcing symptoms. It’s marked by depressive episodes that can give way to years of stable mood before the person has a manic episode months or years later. I can’t think of any way to model this except as some underlying unified tendency toward bipolar disorder – although the ability for this tendency to cause a depression that looks just like normal unipolar depression is a point in NDCB’s favor, since it suggests there can be many different causes for the same syndrome.

The impressive success of ketamine also counts as a point against. NDCB imagine psychiatric disorders like depression as gradually fading out on a symptom-by-symptom basis, eventually reaching a point where enough symptoms are gone that the rest of them aren’t self-reinforcing and just sputter out. This matches the course of eg SSRI treatment, where the medications will gradually improve a few symptoms at at time over the space of a month or so and maybe cause a full remission if you’re lucky. It doesn’t really match ketamine, where every aspect of depression vanishes instantly, then returns after a week or so without treatment. There are a couple of other equally impressive things – staying awake for thirty hours straight, for example, can have an immediate and near-miraculous antidepressant effect, which unfortunately vanishes as soon as you go to sleep. Both of these treatments seem like direct strikes against the One True Cause Of Depression, and both suggest that an underlying tendency toward depression can exist separate from any symptoms (or else why would the depression come back after the effects of the ketamine wore off?)

I don’t think it’s possible to cure depression by blasting every symptom simultaneously. That is, suppose somebody is depressed with symptoms of poor sleep, poor appetite, low energy, suicidality, and low mood. Ambien can make them sleep. Pot can make them eat. Adderall can give them energy. Clozaril can make them stop wanting to kill themselves. And heroin can perk up mood. So if you gave someone Ambien, pot, Adderall, Clozaril, and heroin at the same time, would that cure their depression? I’m pretty sure no one has ever tried this, but I don’t think anyone’s reported exceptional results from less extreme cocktails like Adderall + trazodone + pot, which I’m sure a bunch of people end up taking. This along with the stuff from the last paragraph suggests that if we want to go with this model, maybe we should think less in terms of actual poor sleep and more in terms of dysfunction in the biological system of which sleep is a visible correlate. In that case we could say that Ambien helps the sleep itself but not the underlying dysfunction. But that takes some of the elegance out of the theory.

Despite these issues, I feel like something along these lines has to be true. There are too many things that sort of kind of cause psychiatric problems, and too few things that look like One True Causes. Things that look a lot like schizophrenia can be caused by viral infections in utero, by genetic factors, by hitting your head really hard as a child, by hypoxia during the birthing process, by something something something intestinal tract, by something relating to immigration which seems like it might involve psychosocial stress, and so on. Studies of the immune system, the dopamine system, the glutamate system, and the kynurenine system have all found disruptions. There have been so many really brilliant attempts to reduce all of these to a single brain region, or the levels of one specific chemical, or something that’s simple in the same way that lack-of-insulin-causes-diabetes is simple. But nobody’s ever succeeded. Maybe we should just give up.

I guess I’ve felt for a long time that some kind of weird change in attractor states of biological systems is the best way to explain these kinds of things, but I was never able to express what I meant coherently besides “weird change in attractor states of biological systems”. NDCB offer a clear model that suggests good avenues for future research.

(And I wasn’t joking when I said that little diagram with the two pentagons was the solution to 25% of extant philosophical problems.)