SSC Journal Club: Relaxed Beliefs Under Psychedelics And The Anarchic Brain

[Thanks to Sarah H. and the people at her house for help understanding this paper]

The predictive coding theory argues that the brain uses Bayesian calculations to make sense of the noisy and complex world around it. It relies heavily on priors (assumptions about what the world must be like given what it already knows) to construct models of the world, sampling only enough sense-data to double-check its models and update them when they fail. This has been a fruitful way to look at topics from depression to autism to sensory deprivation. Now, in Relaxed Beliefs Under Psychedelics And The Anarchic Brain: Toward A Unified Model Of The Brain Action Of Psychedelics, Karl Friston and Robin Carhart-Harris try to use predictive coding to explain the effects of psychedelic drugs. Then they use their theory to argue that psychedelic therapy may be helpful for “most, if not all” mental illnesses.

Priors are unconscious assumptions about reality that the brain uses to construct models. They can range all the way from basic truths like “solid objects don’t randomly disappear”, to useful rules-of-thumb like “most get-rich-quick schemes are scams”, to emotional hangups like “I am a failure”, to unfair stereotypes like “Italians are lazy”. Without any priors, the world would fail to make sense at all, turning into an endless succession of special cases without any common lessons. But if priors become too strong, a person can become closed-minded and stubborn, refusing to admit evidence that contradicts their views.

F&CH argue that psychedelics “relax” priors, giving them less power to shape experience. Part of their argument is neuropharmacologic: most psychedelics are known to work through the 5-HT2A receptor. These receptors are most common in the cortex, the default mode network, and other areas at the “top” of a brain hierarchy going from low-level sensations to high-level cognitions. The 5-HT2A receptors seem to strengthen or activate these high-level areas in some way. So:

Consistent with hierarchical predictive processing, we maintain that the highest level of the brain’s functional architecture ordinarily exerts an important constraining and compressing influence on perception, cognition, and emotion, so that perceptual anomalies and ambiguities—as well as dissonance and incongruence—are easily and effortlessly explained away via the invocation of broad, domain-general compressive narratives. In this work, we suggest that psychedelics impair this compressive function, resulting in a decompression of the mind-at-large—and that this is their most definitive mind-manifesting action.

But their argument also hinges on the observation that psychedelics cause all the problems we would expect from weakened priors. For example, without strong priors about object permanence to constrain visual perception toward stability, we would expect the noise of the visual sensorium to make objects pulse, undulate, flicker, or dissolve. These are some of the most typical psychedelic hallucinations:

consider the example of hallucinated motion, e.g., perceiving motion in scenes that are actually static, such as seeing walls breathing, a classic experience with moderate doses of psychedelics. This phenomenon can be fairly viewed as relatively low level, i.e., as an anomaly of visual perception. However, we propose that its basis in the brain is not necessarily entirely low-level but may also arise due to an inability of high-level cortex to effectively constrain the relevant lower levels of the (visual) system. These levels include cortical regions that send information to V5, the motion-sensitive module of the visual system. Ordinarily, the assumption “walls don’t breathe” is so heavily weighted that it is rendered implicit (and therefore effectively silent) by a confident (highly-weighted) summarizing prior or compressive model. However, under a psychedelic, V5 may be forced to interpret increased signaling arising from lower-level units because of a functional negligence, not just within V5 itself, but also higher up in the hierarchy. Findings of impaired high- but not low-level motion perception with psilocybin could be interpreted as broadly consistent with this model, namely, pinning the main source of disruption high up in the brain’s functional hierarchy.

But F&CH are most interested in whether psychedelics can cause the positive effects we would expect of relaxed priors. If overly strong priors cause closed-mindedness, psychedelics should allow users to “see things with new eyes” and change their minds about important issues. These changes would be precipitated by the drug, but not fundamentally about the drug. For example, imagine a person who formed a strong prior around “I am a failure” at a young age, then later went on to achieve great things. Because their prior was so strong, they might think of each of their accomplishments as a special case, or interpret them as less impressive than they were. On psychedelics, they could reexamine the evidence unbiased by their existing beliefs, determine that their accomplishments were impressive enough to count as successes, and abandon the “I am a failure” prior. They would continue understanding that they were successful even after they sobered up, because the change of mind was a triumph of rationality and not a drug-fueled hallucination.

When I was young, I liked a fantasy book called The Sword of Shannara. The titular sword had an unusual magic power: it made the wielder realize anything he already knew. Neither a truly good person nor a truly bad person would benefit from the sword, but someone who was hypocritical, or deluding themselves, or complicit in their own brainwashing, would find all the parts of their mind flung together so hard that they couldn’t help but realize all the inconvenient facts they were trying to repress, or connect all the puzzle pieces previously scattered in separate mental compartments. Sometimes this resulted in a blinding revelation that you were on the wrong side, or had wasted your life; other times in nothing at all. F&CH argue that psychedelics are the real-life version of this, a way to make all of your beliefs connect with each other and see what results from the reaction.

These dignified scientists don’t like magic-sword related analogies, so they stick to regular-sword-related ones. “Annealing” is a concept in metallurgy where blacksmiths heat a metal object in a forge until it undergoes a phase change. All the molecules move to occupy whatever the lowest-energy place for them to occupy is, strengthening the metal’s structure. Then the metal object leaves the forge and the metal freezes in the new, better configuration.

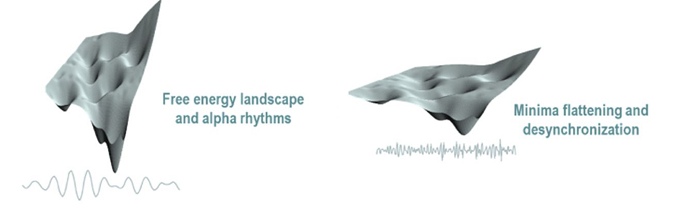

They analogize the same process to “flattening an energy landscape”. Imagine a landscape of hills and valleys. You are an ant placed at a random point in the landscape. You usually slide downhill at a certain rate, but for short periods you can occasionally go uphill if you think it would help. Your goal is to go as far downhill as possible. If you just follow gravity, you will end up in a valley, but it might not be the deepest valley. You might get stuck at a “local minimum”; a valley deep enough that you can’t climb out of it, but still not as deep as other places in the landscape you will never find. F&CH imagine a belief landscape in which the height of a point equals the strength of your priors around that belief. If you settle in a suboptimal local minimum, you may never get out of it to find a better point in belief-space that more accurately matches your experience. By globally relaxing priors, psychedelics flatten the energy landscape and make it easier for the ant to crawl out of the shallow valley and start searching for even deeper terrain. Once the drugs wear off, the energy landscape will resume its normal altitude, but the ant will still be in the deeper, better valley.

Here F&CH are clearly thinking of recent research that suggests MDMA treats post-traumatic stress disorder. Post-traumatic stress disorder is well-modeled as a dysfunctional prior, something like “the world is unsafe” or “you’re still in that jungle in ‘Nam, about to be ambushed”. Many PTSD patients have gone on to live good lives in well-functioning communities and now have more than enough evidence that they are safe. But the evidence doesn’t “propagate”; the belief structure is “frozen” in place and cannot be updated. If psychedelics relax strong priors, they can flatten the energy landscape and allow the ant of consciousness to leave the high-walled “the world is unsafe” valley and test the terrain in “the world is actually okay”. And since the latter is a deeper valley (more accurate belief) than the former, the patient will remain there after the drug trip wears off. This seems to really work; the effect size of MDMA on PTSD is very impressive.

Here F&CH are clearly thinking of recent research that suggests MDMA treats post-traumatic stress disorder. Post-traumatic stress disorder is well-modeled as a dysfunctional prior, something like “the world is unsafe” or “you’re still in that jungle in ‘Nam, about to be ambushed”. Many PTSD patients have gone on to live good lives in well-functioning communities and now have more than enough evidence that they are safe. But the evidence doesn’t “propagate”; the belief structure is “frozen” in place and cannot be updated. If psychedelics relax strong priors, they can flatten the energy landscape and allow the ant of consciousness to leave the high-walled “the world is unsafe” valley and test the terrain in “the world is actually okay”. And since the latter is a deeper valley (more accurate belief) than the former, the patient will remain there after the drug trip wears off. This seems to really work; the effect size of MDMA on PTSD is very impressive.

But the authors want to go further than that. They write:

In this study, we take the position that most, if not all, expressions of mental illness can be traced to aberrations in the normal mechanics of hierarchical predictive coding, particularly in the precision weighing of both high-level priors and prediction error. We also propose that, if delivered well (Carhart-Harris et al., 2018c), psychedelic therapy can be helpful for such a broad range of disorders precisely because psychedelics work pharmacologically (5-HT2AR agonism) and neurophysiologically (increased excitability of deep-layer pyramidal neurons) to relax the precision weighting of high-level priors (instantiated by high-level cortex) such that they become more sensitive to context (e.g., via sensitivity to bottom-up information flow intrinsic to the system) and amenable to revision (Carhart-Harris, 2018b).

“Most if not all” psychiatric disorders. This has some precedent: some people are already thinking of depression as a high-level prior on negative perceptions and events, obsessive-compulsive disorder as strong priors on the subject of the obsession, etc. But it’s is a really strong claim, and Friston himself has previously published models of depression and anxiety that don’t obviously seem to mesh with this. I wonder if this is Carhart-Harris’ overenthusiasm for psychedelics running a little ahead of the evidence.

Speaking of Carhart-Harris’ overenthusiasm for psychedelics running a little ahead of the evidence, the paper ends with a weird section comparing the hierarchial structure of the brain to the hierarchical structure of society, and speculating that just as psychedelics cause an “anarchic brain” where the highest-level brain structures fail to “govern” lower-level activity, so they may cause society to dissolve or something:

Two figureheads in psychedelic research and therapy, Stanislav Grof and Roland Griffiths, have highlighted how psychedelics have historically “loosed the Dionysian element” (Pollan, 2018) to the discomfort of the ruling elite, i.e., not just in 1960s America but also centuries earlier when conquistadors suppressed the use of psychedelic plants by indigenous people of the same continent. Former Harvard psychology professor, turned psychedelic evangelist, Timothy Leary, cajoled that LSD could stand for “Let the State Dissolve” (Pollan, 2018). Whatever the interaction between psychedelic use and political perspective, we hope that psychedelic science will be given the best possible opportunity to positively impact on psychology, psychiatry, and society in the coming decades—so that it may achieve its promise of significantly advancing self-understanding and health care.

Sure, whatever. But this might be a good time to go back and notice some of the slight discordant notes scattered throughout the paper.

In a paragraph on HPPD, F&CH write:

Hallucinogen-persisting perceptual disorder (HPPD) is a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition–listed disorder that relates to enduring visual perceptual abnormalities that persist beyond an acute psychedelic drug experience. Its prevalence appears to be low and its etiology complex, but symptoms can still be distressing for individuals (Halpern et al., 2018). Under the REBUS model, it is natural to speculate that HPPD may occur if/when the collapse of hierarchical message passing does not fully recover. A compromised hierarchy would imply a compromised suppression of prediction error, and it is natural to assume that persistent perceptual abnormalities reflect attempts to explain away irreducible prediction errors. Future brain-imaging work could examine whether aspects of hierarchical message passing, such as top-down effective connectivity, are indeed compromised in individuals reporting HPPD.

In other words, the priors relax and don’t unrelax again after the drug experience.

For example, an especially common HPPD experience is seeing solid objects pulsate, ooze, or sway. It’s not surprising that a noisy visual system would sometimes put the edge of an object in one place rather than another. But usually a strong prior on “solid objects are not pulsating” prevents this from interfering with perception. Relax this prior too far and the pulsating becomes apparent. If the prior stays relaxed after the drug trip ends, you’ll keep seeing the pulsation indefinitely.

This is one of two plausible theories of HPPD, the other being that the hours of seeing objects pulsate makes your brain learn a new prior, “objects do pulsate” and stick to it. This would make more sense in the context of other learned permanent perceptual disorders like mal de debarquement.

F&CH include a section called “What To Do About The Woo?”, where they admit many people who have psychedelic experiences end up believing strange things: ghosts, mysticism, conspiracies. They are not very worried about this, positing that “a strong psychedelic experience can cause such an ontological shock that the experiencer feels compelled to reach for some kind of explanation” and arguing that as long as we remind people that science is good and pseudoscience is bad, they should be fine.

But I still worry that psychedelic woo is the cognitive equivalent of HPPD.

On one reading, it’s the failure of relaxed priors to re-strengthen, so that beliefs that previously had low prior probability – “this phenomenon is explained by ghosts”, “this guy at the subway station preaching universal love has really discovered all the secrets of the universe” – become more compelling. Spiritual beliefs are kind of a Pascal’s Wager type of deal – extremely important if true, but so unlikely to be true that we don’t usually pay much attention to them. If someone is walking around with a permanently flattened energy landscape – if all their probabilities are smushed together so that unlikely things don’t seem that much more unlikely than likely ones – then the calculation goes the other way, and the fascinating nature of these beliefs overcomes their improbability to make them seem worthy of attention.

On the other reading, they’re the result of newly-established priors in favor of ghosts and mysticism and conspiracies. People are not actually very good at reasoning. If you metaphorically heat up their brain to a temperature that dissolves all their preconceptions and forces them to basically reroll all of their beliefs, then a few of them that were previously correct are going to come out wrong. F&CH’s theory that they are merely letting evidence propagate more fluidly through the system runs up against the problem where, most of the time, if you have to use evidence unguided by any common sense, you probably get a lot of things wrong.

F&CH aren’t the first people to discuss this theory of psychedelics. It’s been in the air for a couple of years now – and props to local bloggers at the Qualia Research Institute and Mad.Science.Blog for getting good explanations up before the parts had even all come together in journal articles. I’m especially interested in QRI’s theory that meditation has the same kind of annealing effect, which I think would explain a lot.

But F&CH’s paper lends the theory a new level of credibility. Carhart-Harris is one of the pioneers of psychedelic therapy, and the paper looks like it’s intended to get people more interested in and accepting of that work by providing a promising theoretical basis. If so, mission accomplished.