Book Review: Why Are The Prices So D*mn High?

Why have prices for services like health care and education risen so much over the past fifty years? When I looked into this in 2017, I couldn’t find a conclusive answer. Economists Alex Tabarrok and Eric Helland have written a new book on the topic, Why Are The Prices So D*mn High? (link goes to free pdf copy, or you can read Tabarrok’s summary on Marginal Revolution). They do find a conclusive answer: the Baumol effect.

T&H explain it like this:

In 1826, when Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 14 was first played, it took four people 40 minutes to produce a performance. In 2010, it still took four people 40 minutes to produce a performance. Stated differently, in the nearly 200 years between 1826 and 2010, there was no growth in string quartet labor productivity. In 1826 it took 2.66 labor hours to produce one unit of output, and it took 2.66 labor hours to produce one unit of output in 2010.

Fortunately, most other sectors of the economy have experienced substantial growth in labor productivity since 1826. We can measure growth in labor productivity in the economy as a whole by looking at the growth in real wages. In 1826 the average hourly wage for a production worker was $1.14. In 2010 the average hourly wage for a production worker was $26.44, approximately 23 times higher in real (inflation-adjusted) terms. Growth in average labor productivity has a surprising implication: it makes the output of slow productivity-growth sectors (relatively) more expensive. In 1826, the average wage of $1.14 meant that the 2.66 hours needed to produce a performance of Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 14 had an opportunity cost of just $3.02. At a wage of $26.44, the 2.66 hours of labor in music production had an opportunity cost of $70.33. Thus, in 2010 it was 23 times (70.33/3.02) more expensive to produce a performance of Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 14 than in 1826. In other words, one had to give up more other goods and services to produce a music performance in 2010 than one did in 1826. Why? Simply because in 2010, society was better at producing other goods and services than in 1826.

Put another way, a violinist can always choose to stop playing violin, retrain for a while, and work in a factory instead. Maybe in 1826, when factory owners were earning $1.14/hour and violinists were earning $5/hour, so no violinists would quit and retrain. But by 2010, factory workers were earning $26.44/hour, so if violinists were still only earning $5 they might all quit and retrain. So in 2010, there would be a strong pressure to increase violinists’ wage to at least $26.44 (probably more, since few people have the skills to be violinists). So violinists must be paid 5x more for the same work, which will look like concerts becoming more expensive.

This should happen in every industry where increasing technology does not increase productivity. Education and health care both qualify. Although we can imagine innovative online education models, in practice one teacher teaches about twenty to thirty kids per year regardless of our technology level. And although we can imagine innovative AI health care, in practice one doctor can only treat ten or twenty patients per day. Tabarrok and Helland say this is exactly what is happening. They point to a few lines of evidence.

First, costs have been increasing very consistently over a wide range of service industries. If it was just one industry, we could blame industry-specific factors. If it was just during one time period, we could blame some new policy or market change that happened during that time period. Instead it’s basically omnipresent. So it’s probably some kind of very broad secular trend. The Baumol effect would fit the bill; not much else would.

Second, costs seemed to increase most quickly during the ’60s and ’70s, and are increasing more slowly today. This fits the growth of productivity, the main driver of the Baumol effect. Between 1950 and 2010, the relative productivity of manufacturing compared to services increased by a factor of six, which T&H describe as “of the same order as the growth in relative prices”. This is what the violinist-vs-factory-worker model of the Baumol effect would predict.

Third, competing explanations don’t seem to work. Some people blame rising costs on “administrative bloat”. But administrative costs as a share of total college costs have stayed fixed at 16% from 1980 to today (really?! this is fascinating and surprising). Others blame rising costs on overregulation. But T&H have a measure for which industries have been getting more regulated recently, and it doesn’t really correlate with which industries have been getting more expensive (wait, did they just disprove that regulation hurts the economy? I guess regulation isn’t a random shock, so this isn’t proof, but it still seems like a big deal). They’re also able to knock down industry-specific explanations like medical malpractice suits, teachers unions, etc.

Fourth, although service quality has improved a little bit over the past few decades, T&H provide some evidence that this explains only a small fraction of the increase in costs. Yet education and health care remain as popular (maybe more popular) than ever. They claim that very few things in economics can explain simultaneous increasing cost, increasing demand, and constant quality. One of those few things is the Baumol effect.

Fifth, they did a study, and the lower productivity growth in an industry, the higher the rise in costs, especially if they use college-educated workers who could otherwise get jobs in higher-productivity industries. This is what the Baumol effect would predict (though framed that way, it also sounds kind of obvious).

I find their case pretty convincing. And I want to believe. If this is true, it’s the best thing I’ve heard all year. It restores my faith in humanity. Rising costs in every sector don’t necessarily mean our society is getting less efficient, or more vulnerable to rent-seeking, or less-well-governed, or greedier, or anything like that. It’s just a natural consequence of high economic growth. We can stop worrying that our civilization is in terminal decline, and just work on the practical issue of how to get costs down.

But I do have some gripes. T&H frequently compare apples and oranges; for example, the administrator share in colleges vs. the faculty share in K-12; it feels like they’re clumsily trying to get one past you. They frequently describe how if you just use eg teacher salaries as a predictor, you can perfectly predict the extent of rising costs. But as far as I can tell, most things have risen the same amount, so if you used any subcomponent as a predictor, you could perfectly predict the extent of rising costs; again, it feels like they’re clumsily trying to get something past me. I think I can work out what they were trying to do (stitch together different datasets to get a better picture, assume salaries rise equally in every category) but I still wish they had discussed their reasoning and its limitations more openly.

The main thesis survives these objections, but there are still a few things that bother me, or don’t quite fit. I want to bring them up not as a gotcha or refutation, but in the hopes that people who know more about economics than I do can explain why I shouldn’t worry about them.

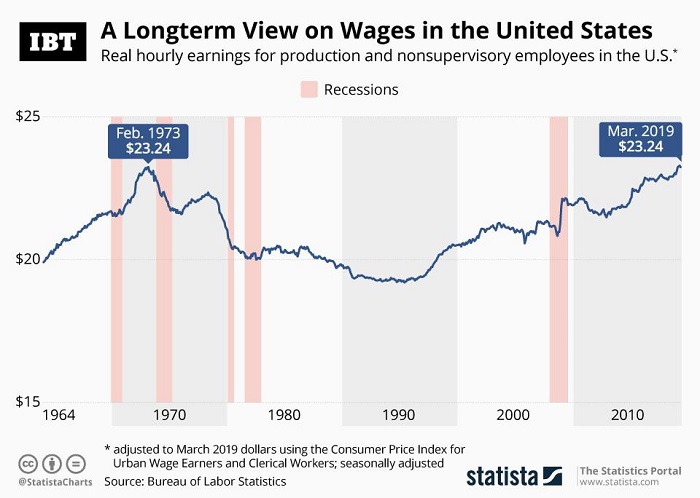

First, real wages have not in fact gone up during most of this period. Factory workers are not getting paid more. That makes it hard for me to understand how rising wages for factory workers are forcing up salaries for violinists, teachers, and doctors.

I discuss whether issues like benefits and inflation can explain this away here here, and conclude they can do so only partially; I’m not sure how this would interact with the Baumol effect.

I discuss whether issues like benefits and inflation can explain this away here here, and conclude they can do so only partially; I’m not sure how this would interact with the Baumol effect.

Second, other data seem to dispute that salaries for the professionals in question have risen at all. T&H talk about rises in “instructional expenditures”, an education-statistics term that includes teacher salary and other costs; their source is NCES. But NCES also includes tables of actual teacher salaries. These show that teacher salaries today are only 6% higher than teacher salaries in 1970. Meanwhile, per-pupil costs are more than twice as high. How is an increase of 6% in teacher salaries driving an increase of 100%+ in costs? Likewise, although on page 33 T&H claim that doctors’ salaries have tripled since 1960, other sources report smaller increases of about 50% to almost nothing. Conventional wisdom among doctors is that the profession used to be more lucrative than it is today. This makes it hard to see how rising doctor salaries could explain a tripling in the cost of health care. And doctor salaries apparently make up only 20% of health spending, so it’s hard to see how they can matter that much.

(also, this SMBC)

Third, the Baumol effect can’t explain things getting less affordable. T&H write:

The cost disease is not a disease but a blessing. To be sure, it would be better if productivity increased in all industries, but that is just to say that more is better. There is nothing negative about productivity growth, even if it is unbalanced.In particular, it is important to see that the increase in the relative price of the string quartet makes string quartets costlier but not less affordable. Society can afford just as many string quartets as in the past. Indeed, it can afford more because the increase in productivity in other sectors has made society richer. Individuals might not choose to buy more, but that is a choice, not a constraint forced upon them by circumstance.

This matches my understanding of the Baumol effect. But it doesn’t match my perception of how things are going in the real world. College has actually become less affordable. Using these numbers: in 1971, the average man would have had to work five months to earn a year’s tuition at a private college. In 2016, he would have had to work fourteen months. To put this in perspective, my uncle worked a summer job to pay for his college tuition; one summer of working = one year tuition at an Ivy League school. Student debt has increased 700% since 1990. College really does seem to be getting less affordable. So do health care, primary education, and all the other areas affected by cost disease. Baumol effects shouldn’t be able to do this, unless I am really confused about them.

If someone can answer these questions and remove my lingering doubts about the Baumol effect as an explanation for cost disease, they can share credit with Tabarrok and Helland for restoring a big part of my faith in modern civilization.