Does Reality Drive Straight Lines On Graphs, Or Do Straight Lines On Graphs Drive Reality?

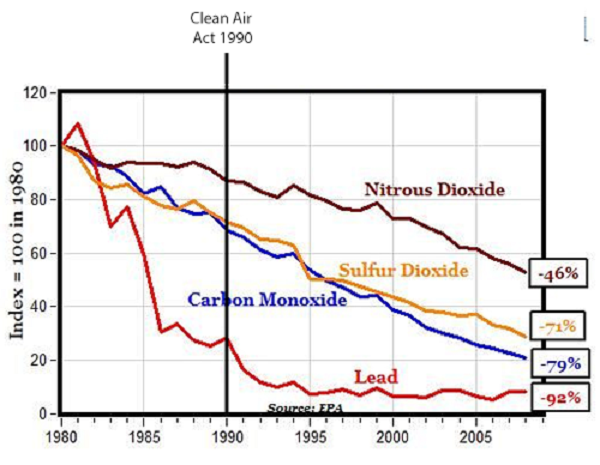

Here’s a graph of US air pollution over time:

During the discussion of 90s environmentalism, some people pointed out that this showed the Clean Air Act didn’t matter. The trend is the same before the Act as after it.

During the discussion of 90s environmentalism, some people pointed out that this showed the Clean Air Act didn’t matter. The trend is the same before the Act as after it.

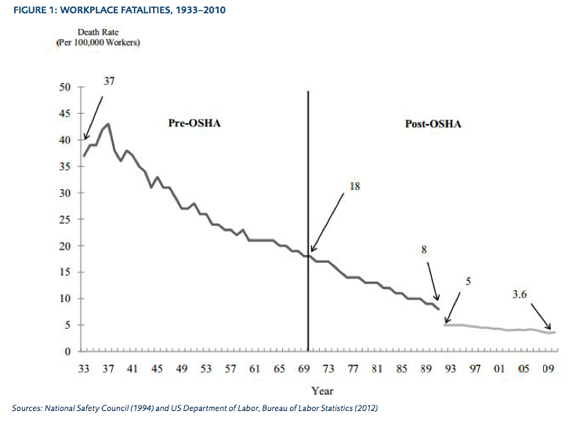

This kind of argument is common. For example, here’s the libertarian Mercatus Institute arguing that OSHA didn’t help workplace safety:

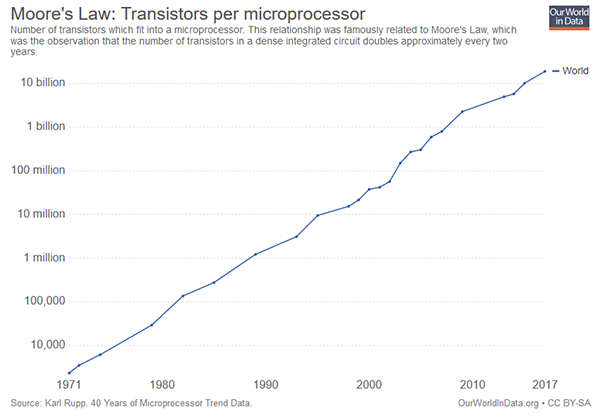

I’ve always taken these arguments pretty seriously. But recently I’ve gotten more cautious. Here’s a graph of Moore’s Law, the “rule” that transistor counts will always increase by a certain amount per year:

I’ve always taken these arguments pretty seriously. But recently I’ve gotten more cautious. Here’s a graph of Moore’s Law, the “rule” that transistor counts will always increase by a certain amount per year:

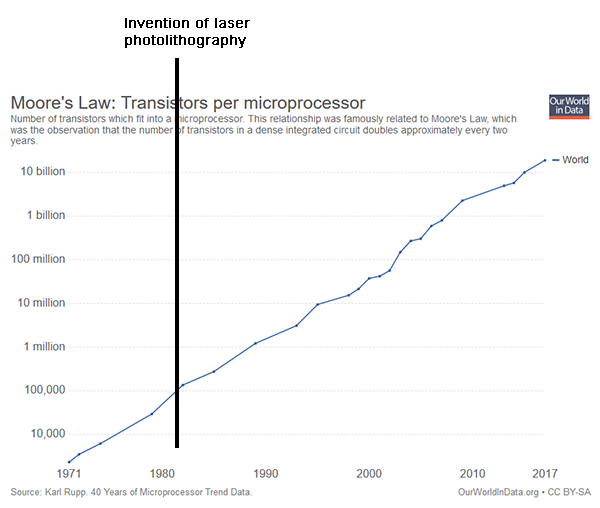

The Moore’s Law Wikipedia article lists factors that have helped transistors keep shrinking during that time, for example “the invention of deep UV excimer laser photolithography” in 1980. But if we wanted to be really harsh, we could make a graph like this:

The Moore’s Law Wikipedia article lists factors that have helped transistors keep shrinking during that time, for example “the invention of deep UV excimer laser photolithography” in 1980. But if we wanted to be really harsh, we could make a graph like this:

But the same argument that disproves the importance of photolithography disproves the importance of anything else. We’d have to retreat to a thousand-coin-flips model where each factor is so small that it happening or not happening at any given time doesn’t change the graph in a visible way.

But the same argument that disproves the importance of photolithography disproves the importance of anything else. We’d have to retreat to a thousand-coin-flips model where each factor is so small that it happening or not happening at any given time doesn’t change the graph in a visible way.

The only satisfying counterargument I’ve heard to this is that Moore’s Law comes from a combination of physical law and human commitment. Physical law is consistent with transistors shrinking this quickly. But having noticed this, humans (like the leadership of Intel) commit to achieve it. That commitment functions kind of as a control system. If there’s a big advance in one area, they can relax a little bit in other areas. If there’s a problem in one area, they’ll pour more resources into it until there stops being a problem. One can imagine an event big enough to break the control system – a single unexpected discovery that cuts sizes by a factor of 1000 all on its own, or a quirk of physical law that makes it impossible to fit more transistors on a chip without inventing an entirely new scientific paradigm. But in fact there was no event big enough to break the control system during this period, so the system kept working.

But then we have to wonder whether other things like clean air are control systems too.

That is, suppose that as the economy improves and stuff, the American people demand cleaner air. They will only be happy if the air is at least 2% cleaner each year than the year before. If one year the air is 10% cleaner than the year before, environmentalist groups get bored and wander off, and there’s no more progress for the next five years. But if one year the air is only 1% cleaner, newly-energized environmentalist voters threaten to vote out all the incumbents who contributed to the problem, and politicians pass some emergency measure to make it go down another 1%. So absent some event strong enough to overwhelm the system, air pollution will always go down 2% per year. But that doesn’t mean the Clean Air Act didn’t change things! The Clean Air Act was part of the toolkit that the control system used to keep the decline at 2%. If the Clean Air Act had never happened, the control system would have figured out some other way to keep air pollution low, but that doesn’t mean the Clean Air Act didn’t matter. Just that it mattered exactly as much as whatever it would have been replaced with.

If this were true, you wouldn’t see the effects of pollution-busting technologies on pollution. You’d see them on everything else. For example, suppose that absent any other progress on air pollution, politicians would regulate cars harder, and that’s what would make air pollution go down by 2% that year. In that case, the effects of inventing an unexpected new pollution-busting technology wouldn’t appear in pollution levels, they would appear in car prices. Unless car prices are also governed by a control system – maybe car companies have a target of keeping costs below $20,000 per car, and so they would skimp on safety in order to bring prices back down, and then the effects of a new anti-pollution technology would appear in car accident fatality rates.

How do we tell the difference between this world, and the world where the Clean Air Act really doesn’t matter? I’m not sure (does anyone know of research on this?). Maybe this is one of those awful situations where you have use common sense instead of looking at statistics.

I’m worried this could be a fully general excuse to dismiss any evidence that a preferred policy didn’t work. But it does make me at least a little slower to believe arguments based on interventions not changing trends.