The Dark Side Of Divorce

A while ago I read The Nurture Assumption

The argument was that there are lots of studies showing that parenting has important effects – for example, if parents yell at their kids, their kids will turn out angry and violent, or something. But these studies neglect possible genetic contributions – angry violent parents are more likely to yell at their kids, so maybe the kids are just inheriting genes for anger and violence. A lot of parenting studies are subject to these kinds of confounds. And one of the best tools we have for disentangling them – behavioral genetics twin studies – very consistently show that most important outcomes are 50% genetically determined, 50% determined by “non-shared environment”, and almost completely unrelated to the “shared environment” of parenting. Therefore, we should conclude that pretty much all of the effect supposedly due to parenting is in fact due to genetics, and it doesn’t matter much what kind of “parenting style” you use unless it can somehow change your child’s DNA.

One of the stories I most remember from the book – and I’m sorry, I don’t have a copy with me, so I’m going from memory – was about the large literature of studies showing that children of divorce raised by single mothers have worse outcomes than children of intact two-parent families. This seems like a convincing argument that children need both parents to develop properly, which if true would be a shared environmental effect and an example of why good stable parenting is necessary.

But other studies found that children who lost a father in (for example) a car accident had outcomes that looked more like those of children from stable two-parent families than like those of children of divorce. So maybe the divorce effect doesn’t reflect the stabilizing influence of two parents in a kid’s life. Maybe it reflects that the sort of genes that make parents unable to hold a marriage together have some bad effects on their kids as well.

(damn you, Rs7632287! This is all your fault!)

It’s compelling, it’s believable, and I believed it. Unfortunately, I recently had the time to double-check, and it doesn’t seem to be true at all.

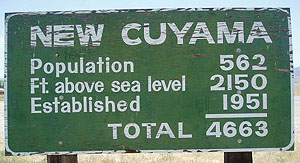

The best introduction to divorce research I could find was Amato & Keith’s meta-analysis Parental Divorce And The Well-Being Of Children. It looks through 92 studies that compare children of divorced and non-divorced families and finds that “children of divorce scored lower than children in intact families across a variety of outcomes, with the median effect size being 0.14 of a standard deviation,” this last clause of which is almost New Cuyaman in its agglomerativeness.

This is a small effect size, and indeed most of the studies they’re looking at aren’t even significant. But once agglomerated together they become very significant, and the analysis tries to determine the cause. The most popular proposed causes are “children in divorced families lose the benefits of having two parents”, “children in divorced families are in economic trouble”, and “children in divorced families have to deal with stressful family conflict.”

This is a small effect size, and indeed most of the studies they’re looking at aren’t even significant. But once agglomerated together they become very significant, and the analysis tries to determine the cause. The most popular proposed causes are “children in divorced families lose the benefits of having two parents”, “children in divorced families are in economic trouble”, and “children in divorced families have to deal with stressful family conflict.”

Although there’s a little bit of evidence for all three, in general the evidence lines up for the last one of these – the family conflict hypothesis.

If the problem is not enough parents or not enough money, then having the custodial parent (usually a single mom) remarry ought to help a lot, especially if she marries somebody wealthy. But usually this doesn’t help very much at all.

If the problem is not enough money, then children of divorce should do no worse than children of poor two-parent families. But in fact they do, and children of divorce still do worse when controlled for income.

If the problem is not enough parents or not enough money, then these ought to persist over time if the custodial parent doesn’t remarry or get richer. But if the problem is stressful conflict, then it ought to get better over time, since the stress and conflict of the divorce gradually becomes more and more remote. Although there are some dueling studies here, the best studies seem to find the latter pattern – bad outcomes of divorce gradually decrease over time.

If the problem is stressful conflict, then children of divorce ought to do no worse than children in families full of stressful conflict who are nevertheless staying together. Indeed, controlling for the amount of stressful conflict within a family gets rid of most of the negative effect of divorce.

Therefore, although there was some evidence for all three hypotheses, the stressful conflict hypothesis was best-supported. But the stressful conflict hypothesis could also explain the pattern where kids whose fathers died in car accidents don’t show the same pattern of problems as children of divorce. Having a parent die in an accident is no doubt traumatic, but it’s a very different kind of trauma from constant familial yelling and bickering.

More to the point, the genetic explanation of divorce has been investigated specifically in at least four studies that I know of, using different methodology each time.

Brodzinsky, Hitt, and Smith studied the effect of divorce on biological versus adopted children. They were unable to find any differences in the level of disruption and poor outcomes.

O’Connor, Caspi, DeFries, and Plomin (yes, that Plomin) also studied biological versus adopted children. They found that biological children showed a stronger effect on academic achievement and social adjustment (consistent with genetic explanations), but adopted children showed an equal effect on behavioral problems and substance use (consistent with environmental explanations).

Burt, Barnes, McGue, and Iacono use a different methodology and compare children whose parents divorced when they were alive with children whose parents divorced before they were born. Presumably, only the former group get any environmental stress from the divorce, but both groups suffer from any genetic issues that caused their parents to split. They find that the negative effects of divorce are mostly limited to the group whose parents got divorced when they were alive, consistent with an environmental explanation.

Finally, a bunch of people including Eric Turkheimer get the requisite twin study in and compare the children of pairs of identical twins where one of them got divorced and the other didn’t (where do they find these people?) Somehow they scraped together a sample size of 2,554 people, and they found that even among children of identical twins, the children of the divorced twin did worse than the children of the non-divorced twin to a degree consistent with the negative effects not being genetic. They tried to adjust for characteristics of the twins’ spouses, but that’s the obvious confound here. I look forward to seeing if future researchers can get a sample of pairs of identical male twins who married pairs of identical female twins, one couple among whom got divorced.

So I owe mainstream psychology an apology here. I was pretty sure they had just completely dropped the ball on this one and were foolishly assuming everything had to be social and nothing could be genetic. In fact, they were only doing that up until about ten or twenty years ago, after which point they figured it out and performed a lot of studies, all of which supported their idea of the stress of divorce having significant (though small!) non-gene-related effects.

And although I haven’t had time to look through them properly yet, here’s a study claiming that the association between fathers’ and childrens’ emotional and behavioral problems is “largely shared environmental in origin”. And here’s a study claiming that “analyses revealed that [shared environment] accounted for 10%-19% of the variance within conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, anxiety, depression, and broad internalizing and externalizing disorders, regardless of their operationalization. When age, informant, and sex effects were considered, [shared environment] generally ranged from 10%-30% of the variance.”

So the shared environment folks haven’t completely dropped the ball, some of them seem to be fighting back, and it will be interesting to see where this goes and whether anybody is able to reconcile the different evidence.

One likely talking point: shared environment and childhood situation obviously impacts things during childhood. For example, if you have parents who are mean and abusive, this can make you stressed and you don’t get enough sleep and then maybe you do really badly at school. But once you get out of that environment, your academic abilities will revert to whatever your genes say they should be. The Nurture Assumption never denies this and is absolutely willing to admit that shared environment can affect outcomes during childhood, although even there less than one might expect. This also seems to be the tack Plomin is taking when he discusses the Burt study.

But studies have found that the negative effects of divorce can last well into adulthood. On the other hand, none of those studies have been the ones that compare genetic and environmental effects, and I get the feeling their quality is kind of weak. So it’s not completely ruled out by the data that the short-term effects of divorce are robust and environmental, but the long-term effects of divorce are spurious and/or genetic. But this seems kind of like fighting a rearguard action against the evidence.

Finally, a sanity check. Suppose your parents get divorced when you’re 16. Your high school grades drop and your behavior gets worse. Maybe you fail a couple of classes and start using drugs. The couple of classes failed mean you’re going to a second-tier instead of a first-tier college, and the drug use means you’re addicted. How does that not affect your life outcomes, even if five years later you’ve forgotten all about whatever psychological stresses you once had?

Overall I am less confident than before that shared environment is harmless.

And while I’m bashing Nurture Assumption, I don’t remember the exact arguments used against birth order effects, but we found such impressive numbers on the last Less Wrong survey that I’m not very impressed with the claims that they don’t exist.