Thin Air

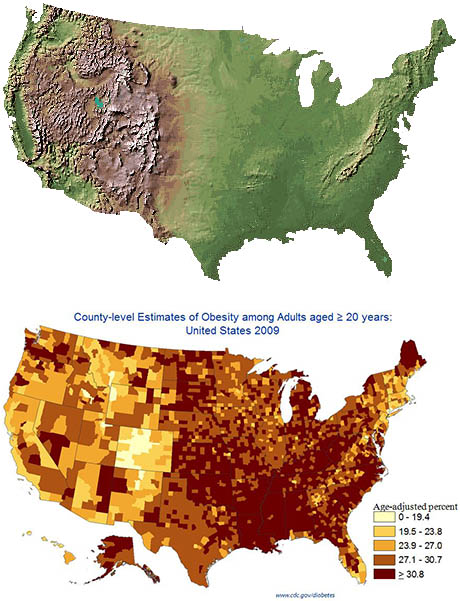

The International Journal of Obesity (h/t amaranththallium) points out a correspondence between US topography and US obesity rates:

It’s easy to see the Rocky Mountains on the obesity map. Not too hard to see the Appalachians either. Squint a little and you can even see California’s Central Valley vs. its coastal ranges.

It’s easy to see the Rocky Mountains on the obesity map. Not too hard to see the Appalachians either. Squint a little and you can even see California’s Central Valley vs. its coastal ranges.

This doesn’t seem to be related to poverty or population density. It does look a lot like the map of exercise level, but apparently it stays significant even when you control for that.

The IJO study finds that people living at sea level are five times more likely to be obese than people living at 500m elevation, even after controlling for “temperature, diet, physical activity, smoking, and demographic factors”. I don’t always trust controlling for things, but in this case the effect is big enough, and similar enough to the results of eyeballing, that it seems pretty plausible. Also, European studies find the same effect in high-altitude areas there, as do studies in Tibet. And someone did a study on US soldiers, who are randomly assigned (via deployment) to different areas, and found the same effect controlling for BMI at enlistment.

(on the other hand, a study in Saudi Arabia finds the opposite. Whatever. I didn’t even know Saudi Arabia had mountains.)

So what’s going on? There’s a well-known phenomenon called altitude anorexia where lowland people going to a high altitude suddenly can lose a lot of weight. Unfortunately most of the studies just stop at showing an acute effect; it’s not clear how long it lasts or whether there are more general principles involved. One study on rats found that they ate 58% less one day after being transported to Pike’s Peak, and were still eating 16% less per day two weeks afterwards. An article in High Altitude Medicine noted without further details that altitude anorexia seemed to persist after initial acclimatization. Pugh et al note weight loss of 1 kg/week up to 5-10 kg over a several week Everest ascent, reversing quickly as the climbers descended. A controlled experiment where obese subjects were ferried to the Swiss Alps, told to eat as much as they want, and banned from exercising resulted in weight loss of three pounds after a week, mostly sustained (?!) after a month at low altitude. It seemed mediated by eating less, which was independent of altitude sickness and persisted after people were no longer altitude-sick.

The active ingredient of altitude seems to be hypoxia. The air is thin at high altitudes so the body gets less oxygen. Being in low oxygen conditions in normal pressure seems to cause weight loss too – see here and here for studies of people exercising in low oxygen conditions. I don’t know of any studies where people were just kept in low-oxygen environments for a long time without exercise to see what happened to their weight. It’s not really clear how reduced oxygen makes people eat less. A lot of people mention leptin, but the studies seem pretty unconvincing, and people try to work leptin into everything.

This BMJ editorial suggests that hypoxia should get credit for smoking-related weight loss. But it reads like a completely unhinged screed from the tobacco lobby of an alternate dimension (“Might the aggressive anti-smoking lobby have contributed to the costly epidemic in obesity and type 2 diabetes that Professor Sir George Alberti have warned us about?”) so maybe we shouldn’t take it too seriously. Also, nicotine gum works just as well as cigarettes here, so it’s probably an effect of the nicotine itself, and in fact we have some pretty good ideas how this happens. Maybe unhinged screeds by alternate-universe tobacco lobbies aren’t the most trustworthy source of information.

Anyway, this is boring. Let’s move on to a more interesting question – did global warming cause the obesity epidemic?

The arguments in favor: there’s a lot more carbon dioxide in the air now than there was just a few decades ago. The obesity epidemic began around the time carbon dioxide concentrations really started getting worrying. And there are various body functions that are exquisitely dependent on CO2 levels. Bierworth (2014) has a good run-down of some of these and how they might be affected by increasing atmospheric CO2 levels (dear conservatives who always talk about Chesterton’s Fence and principle of precaution – has it occurred to you that doubling the concentration of a major bioactive atmospheric gas might be a bad thing?). I see some conflicting claims about how much atmospheric CO2 could affect average blood pH. Neurons that produce obesity-regulating chemical orexin are potentially very sensitive to blood pH, so maybe this could be involved?

Wild animals are affected by the obesity epidemic too, even though they eat far fewer Big Macs. Even lab rats and zoo animals, supposedly kept on a well-monitored diet, are heavier now than they were decades ago. It’s hard to think of some obesogenic factor so prevalent that it could seep into laboratories and zoos unnoticed by scientists and zookeepers. If it were a chemical, it would have to be really prevalent. The xenoestrogens in the water are one possiblity. But the other is the atmospheric gas breathed in by every living thing which we already know has been increasing for decades.

This at least is the theory of epidemiologist Lars George Hersoug. He did a study where he put some people in a high-CO2 room and found that they gained weight. It got a decent amount of press.

I really like this theory. It’s elegant. It’s clever. It’s at exactly the right level of contrarianism to be fun. If it were true, it would solve global climate change – once tabloids covers trumpet THE ONE SECRET TO A TIGHT BELLY DOCTORS DON’T WANT YOU TO KNOW – TELL YOUR CONGRESSMAN TO PASS THE PARIS AGREEMENT TO LIMIT CLIMATE CHANGE TO WITHIN 2 DEGREES CENTIGRADE OF PRE-INDUSTRIAL LEVELS, we will finally get Middle America on board. Insofar as scientific theories can be “fun”, this theory is fun.

But I grudgingly acknowledge that it’s probably not true.

For one thing, the study involved kind of sucks. It has a sample size of six. The six people were in a chamber that elevated CO2 levels about 50x higher than human industrial activity has elevated them in the atmosphere. And it got a non-significant result. In fact, food intake decreased in three of the six subjects, with almost all of the (nonsignificant) positive trend coming from one guy who apparently was just really hungry that day. There is a decent study showing CO2-related orexin effects in mice, but it’s at 2000x atmospheric concentrations. Also, when I look at the orexin neuron calculations, even if their hypothesis is true it suggests that orexin neurons might fire a little less than 1% more often now than they did 100 years ago. Unless there’s something really nonlinear going on, this is not enough to cause an epidemic.

For another, it doesn’t seem to line up geographically. Zheutlin, Adar, and Park try to correlate the geography of US obesity with the geography of US atmospheric CO2 in the same way that some of the studies above successfully correlated US obesity with US altitude. Here they fail. After adjusting for appropriate confounders, there is no clear relationship between CO2 levels and obesity. I think this might also reflect a more general point, which is that CO2 has been rising all over the world but obesity hasn’t; Japan, for example, is a very high CO2 emitter but has almost totally avoided a US-level obesity crisis.

(but while we’re talking about this study, it did find that serum bicarbonate has been increasing over the past decade or two. No proof as yet that this is a real effect or related to CO2, but have I mentioned that increasing the concentration of a bioactive atmospheric gas worldwide is a really bad idea?)

One last counterargument. A global warming skepticism blog points out that submarines are a natural laboratory for the effect of high CO2 on human health, since they usually have CO2 levels up to ten times atmospheric (and several times worse than even a poorly-ventilated building). I don’t see any formal tests of their own argument, which is that submariners don’t suffer any cognitive problems, and I’m not sure they’re right to use intuition and failure to notice gross impairment – after all, the original studies showing impairment were done in office buildings, and there’s no grossly noticeable differences there. But in any case, the Navy actually did a formal study and found that submariners do not gain weight. This seems pretty fatal for a CO2 = weight gain theory.

So my guess is that Hersoug is wrong and CO2 doesn’t cause appreciable weight gain in normal concentrations. We should abandon the beautiful theory of climate-change-induced obesity and go down a level of contrarianism to blaming boring normal-person things like xenoestrogens and gut microbiota.

(I’ve heard there are theories of obesity even less contrarian than those, but I’ve never been to such low contaranianism levels and wouldn’t be able to tell you what they might be.)