[ACC] Is Eating Meat A Net Harm?

[This is an entry to the 2019 Adversarial Collaboration Contest by David G and Froolow. Please also note my correction to yesterday’s entry.]

Introduction

Many people around the world have strong convictions about eating animals. These are often based on vague intuitions which results in unproductive swapping of opinions between vegetarians and meat eaters. The goal of this collaboration is to investigate all relevant considerations from a shared frame of reference.

To help ground this discussion we have produced a decision aid making explicit everything discussed below. You can download it here and we encourage you to play around with it.

The central question is whether factory farmed animal lives are worth living; the realistic alternative to meat eating is not a better life but for those animals to not exist in the first place.

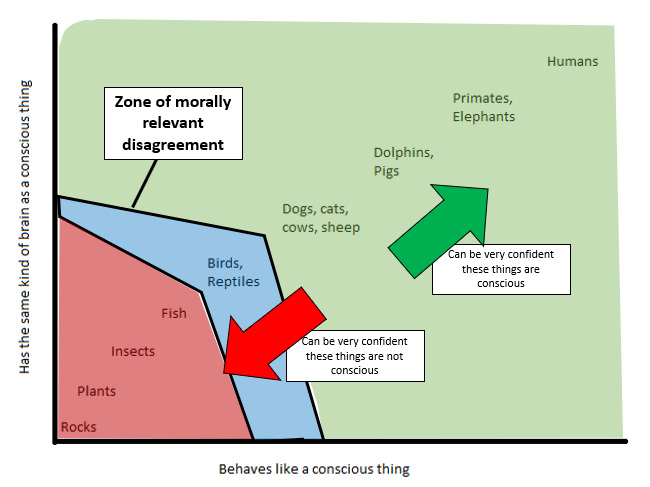

We begin by investigating which animals are conscious. Then, we compare the happiness literature to the conditions under which animals are factory farmed to figure out if from their perspective non-existence is preferable. And finally, we survey the more easily measurable impacts of meat eating on environment, finance, and health.

1. Consciousness

1.1. What is consciousness?

This essay isn’t about a general theory of consciousness. We tried to research this and our main takeaway is simply that consciousness is really, really weird. When we say that something is ‘conscious’ we mean simply that it’s ‘like something to be that thing,’ and that if we were that thing we’d care if ‘good’ or ‘bad’ things happened to us.

Of particular relevance is the conscious experience of pain and suffering, which we regard as morally undesirable when it occurs in ourselves or others. Most animals have damage sensors, but triggering these may not result in the subjective experience of ‘suffering’ if the animal is not conscious or the stimulus is a constant presence that has been accustomed to.

And this is the absolute crux of this investigation; if animals suffer under current farming standards to the point of preferring non-existence then there is a moral burden on meat eaters to justify eating them.

To resolve this, we will look for in different animals at two kinds of evidence for consciousness:

1. A brain architecture similar to humans resulting from the same evolutionary process

2. Behaviors that are hard to explain except with reference to having experiences

1.2. What parts of the brain are ‘responsible’ for consciousness?

You might assume consciousness is just caused by ‘the brain,’ because without it how could we think (or do) anything? However, a huge part of intelligent information processing happens in our brain without giving rise to conscious experience.

Try noticing what happens when you read the sentence “The dustmen said they would refuse to collect the refuse without a raise.” Notice how the word ‘the’ appeared twice? And how you read it both times despite Scott’s best efforts at conditioning you otherwise? Very good. Now, notice also that the word “refuse” appeared twice, but the first time you not only interpreted it but heard in your mind as a verb with the stress on the second syllable, and the second time as a noun. Before the words appeared in your conscious mind, as visual on a screen, as sound in your head, as a feeling of understanding the sentence, your brain already did all the hard parts of figuring out what they mean subconsciously, without you experiencing anything.

If you sever the spinal cord, the 1 billion nerve cells in the backbone connecting your brain to your limbs, you would lose complete sensation below the neck but you would continue to have thoughts and rich experiences. Or consider the cerebellum, the 69 billion (80%+) neurons which are responsible for motor control. If you cut off parts of it you may lose the mechanic ability to execute certain motions like playing a piano or walking but you will remain completely conscious with a sense of self, a memory, and the ability to plan for the future.

What is in common between the spinal cord and the cerebellum? The neural circuits operate in parallel with hundreds of independent input/output logic gates and all fire one way, instead of forming an interconnected multi-way circuit. There is no capacity for reflection, just predefined decision making. A necessary condition for consciousness (in people) is two neurons ‘talking’ to each other, rather than just passing information with deterministic modification up the chain of command.

Where consciousness appears to be generated is the posterior cerebral cortex, the outer surface of the brain composed of two highly folded sheets. Stimulate it electromagnetically and it’s like any other acid trip. The folded physical structure seems extremely important for generating consciousness because it maximizes the surface area exposure of neurons to each other. Many parts of your brain can be removed without major changes to your personality of intelligence, but if even small parts of the posterior cortex are missing surgery patients lose entire classes of conscious content: awareness of motion, space, sounds, etc.

It’s important to recognize that consciousness is not simply ‘caused by anything that happens in your brain.’ It’s a specific, fragile thing with distinct characteristics that differ from other neural activity that we associate with intelligence – therefore the relative intelligence of animals to humans does not necessarily map closely to their degree of consciousness.

1.3. Neural indicators of consciousness

All mammals have a cerebral cortex. Mice and rats have a smooth one; cats and dogs have some folding; and humans/dolphins/elephants have highly expanded and folded cortices. Therefore all mammals are probably conscious, although with large differences in vividness and complexity.

Birds and reptiles are a harder case because their brain evolution diverged much earlier. They have instead a cluster of neurons with chemical markers associated with differentiated layers of the neocortex but without the folded shape that maximizes connectivity.

By contrast, fish do not have any neural architecture unique to the consciousness-related parts of the brain and are probably unable to feel fear or pain in the way a human would – we strongly encourage you to read this article in full to convince yourself of this claim. Although fish show pain-like responses to harmful stimulus and do so less if given painkillers, this is true even when the entire telencephalon (which includes the forebrain) is removed so on balance it is unlikely they are having a qualitative experience to accompany that response.

1.4. Behavioral indicators of consciousness

Behavior seems like an obvious place to look for evidence of consciousness. However, any behavior can be explained by intelligence alone, or even sub-intelligent evolutionary ‘hard coding’. If you swat a fly, it will make loud ‘angry’ noises and go away. Your little brother would react the same. If you knew nothing about the neural architecture of flies, you might conclude that flies are just as conscious and capable of suffering as people.

One way around this is if we can design tests that indirectly look for mental states, such as the mirror test (whether an animal can recognize its reflection). But elephants (definitely conscious) routinely fail and at least one fish has passed, so we are wary about assigning much weight to these tests.

Another is to look for behaviors that map onto extremely complex emotional states that we observe in humans. If there is a large difference in intelligence but a great similarity in behavior, we can infer that the animal is having a similar conscious experience.

Starting simple; if you play with a dog it will act in the highly specific ways you might if you were feeling ‘joy.’ From a hormonal and intelligence perspective, stress and positive excitement are very similar states, and in non-conscious creatures we would have no reason to expect – for example – a creature to seek out stressors like a chew toy unless they had some positive feelings towards them. That we can so clearly tell how a dog is feeling is to us highly persuasive evidence of consciousness.

Dogs also exhibit something quite analogous to a theory of mind, for example they will comfort their owner if their owner is sad (but maybe this is a learned behavior)

Dogs are unlikely to be a special case; other animals of varying intelligence also exhibit complex behaviors indicative of consciousness:

• Chimps who see another chimp lose a fight will direct more grooming behavior towards the loser, but not if they don’t see that chimp lose the fight. [Link, popular coverage]

• Corvids who hide a treat when being observed will sneak back later and rehide the treat somewhere else, indicating (perhaps) a theory of mind and (certainly) ‘mental time travel’ of imagining the self in various future states. [Link, popular coverage]

• Dolphins given a test to discriminate between X and Y for a reward, but including the option of ‘bailing out’ of the test in exchange for a lesser reward, will bail out more often in more difficult tests, indicating a theory of metacognition (which we’d say is adjacent to – if not the same thing as – a theory of mind). [Link, popular coverage]

Spending time with animals (higher mammals, especially) makes it extremely hard to imagine they are anything but conscious, but we recognize that any behavior could be explained as an expression of intelligence without assuming conscious experience. However, we are reasonably confident that:

1. The range and complexity of behaviors conducted by animals correlates closely with the brain architecture we believe causes consciousness – the more complex the brain architecture, the more consciousness-like the behavior. This would be a substantial coincidence if in fact animals were not conscious.

2. Animals we intuit as conscious are less likely to exhibit ‘glitching’ behavior indicative of being a non-conscious rule-following automaton. There are many examples of ‘glitches’ in insect behavior (such as ant vortexes of death, repetitive digger wasp behavior [although maybe not] and moths failing to notice they are circling a candle), whereas there are very few examples of ‘glitches’ in mammal behavior. A humorous example of a glitch in bird behavior can be found in YouTube videos where the ‘imprinting mechanism’ of ducklings has confused them into thinking a dog is their mother.

1.5. What animals are conscious?

It’s fair to reflect on the uncertainty in the above, but we’d be comfortable ascribing consciousness on the basis of neural architecture and behavior as follows:

There is good reason to believe all common land-based food mammals (cows, pigs, sheep, goats) are highly consciousness. On the other side, we think we can be reasonably confident fish don’t suffer in a morally relevant way. We’re not sure about chickens. We encourage you to read this overview of their behavior in full to convince yourself that their emotional and cognitive intelligence would group them with simple mammals if they had the same neural architecture.

There is good reason to believe all common land-based food mammals (cows, pigs, sheep, goats) are highly consciousness. On the other side, we think we can be reasonably confident fish don’t suffer in a morally relevant way. We’re not sure about chickens. We encourage you to read this overview of their behavior in full to convince yourself that their emotional and cognitive intelligence would group them with simple mammals if they had the same neural architecture.

However, since in most parts of the human brain ‘intelligence’ does not correspond to ‘consciousness,’ and because chicken brains are a clump of neurons with a different evolutionary history and lacking the distinct layered and highly folded structure of the cerebrum, in the model we assume their likelihood of consciousness is 75%.

A key part of this post is to quantify vague feelings about animal consciousness. This is similar to what Scott did with a sample of Tumblr respondents here and SSC reader Tibbar did with an MTurk sample here. Their results are expressed in terms of an animal’s ‘worth’ relative to a human in percentage terms.

% Consciousness

Tumblr sample

MTurk sample

Human

100

100

Chimp

20

50

Elephant

14

100 (!)

Pig

3

20

Cow

2

33

Chicken

0.2

4

Lobster

0.03

1.6

However, it’s important to make the distinction between ‘worth of experience’ and ‘worth of suffering’ because while we might rather be a human than a chicken on a good day, feeling pain might be equally unpleasant in either body. Below is our best guess for a ‘universal’ estimate (i.e. even a meat eater ought to agree that these are plausible) – people who place a premium on animal experience, such as many vegetarians, would likely rate animal experiences higher:

%Weight Suffering

%Weight Experience

Human

100

100

Chimp

90

50

Elephant

90

35

Pig

80

25

Cow

50

10

Chicken

10

1

Lobster

0.1

~0

What we mean by the above is, for example, if the unit of suffering was ‘being boiled alive,’ based on our understanding of how vivid their sense data would be assuming consciousness we would be roughly indifferent between being boiled once as any of a human, chimp, or elephant, 10 times as a chicken, or 1000 times as a lobster. However, we would be indifferent between living (assuming no scarcity or predators) for 1 year as a human, 2 as a chimp, 4 as a pig, or 100 as a chicken.

In the model, the moral impact of a farmed animal is its likelihood of consciousness times the moral weight of its suffering if its life is, based on information in the following sections, ‘worse than non-existence,’ otherwise the moral weight of its existence.

2. How many animals are farmed and under what conditions?

2.1. Animals eaten per capita

The OECD records the exact weight of meat consumed per year, and so by dividing this by the carcass weight we get the per-year per-capita animal consumption by country. This is consistent with other estimates on the web.

Animals / Capita consumed by four major categories in 2018

Australia

Canada

EU27

UK

USA

World

BEEF

0.05

0.05

0.03

0.03

0.07

0.02

PIG

0.27

0.20

0.44

0.22

0.29

0.15

POULTRY

29.42

22.53

15.70

18.53

33.12

9.44

SHEEP

0.38

0.05

0.07

0.22

0.02

0.09

The conditions most animals are farmed in may surprise you. Since a few large factory farms account for most animals farmed, the typical farm may well be a small mom-and-pop operation but the typical food animal is raised on an industrial scale. Further, ‘ag gag’ laws limit facts about animal conditions reaching public awareness and are arguably designed explicitly to allow companies to mislead consumers about the conditions most animals are farmed in.

Animal rights organizations will frequently quote a study by the Sentience Institute that over 99% of animals eaten in the US are factory farmed. Although a biased source, it’s consistent with other government estimates and we get similar results when replicating their methodology with USDA figures. What really drives this statistic is, as seen above, chickens form the vast majority of the farmed animal count and are almost exclusively farmed industrially.

My

calculation for % factory farmed using Sentience Institute

methodology

Sentience

Institute estimate for % factory farmed

BEEF

64%

70%

PIG

94%

98%

POULTRY

~100%

~100%

SHEEP

64%

(based on being woolly cows)

Not

included

Comparing across countries is difficult, but it seems that America is slightly more industrialized than the EU. My best estimate is that the difference is not significant enough to make a moral difference. If you eat meat and cannot explicitly trace the source you are most likely eating factory farmed meat.

2.2. What is it like to be farmed industrially?

The definitive feature of factory farming is that market incentives lead to a paperclip maximizer situation where producing as many animals as possible takes precedent over concerns about animal welfare. Consequently, the ‘experience’ of being factory farmed is best understood as a particular form of slavery where cruelty is the side effect of a system designed to maximize economic output.

2.2.1. Chickens

Chickens can be raised in two ways: in cages or in a shed. Cage-rearing chickens is typical in developing economies such as China, but in the West cages are used for egg laying hens only. Slaughter chickens in the West are raised instead in a large ‘broiler’ shed covered with liter.

Broadly speaking, caged chickens have literally no human analogue in terms of how much they suffer. They live in a state of constant pain and anxiety, barely able to move. The only mercy is that they do not suffer for long. In this analysis we focus on meat-eating in a Western context. So, we model 100% of chickens as being broiler farmed.

A factory farmed slaughter chicken lives for approximately 47 days, during which time it grows to a weight of 2.6kg (42 days and 2.5kg in the EU). This is analogous to a newborn human baby reaching adult weight by the first birthday. To achieve this rapid weight onset, a combination of force-feeding, drugs and high-energy feed is used. But the worst culprit is selective breeding. In a study by Kestin, between 2% and 30% of broiler chickens, depending on the breed, had a gait score between 3 and 5 on a 5 point scale (1 no issues, 3 obvious gate defect, 5 unable to move at all). But 100% of a control group bred randomly and then raised under the same conditions had no or minor mobility issues. Selection for quick growth rather than fitness in the wild leads to a high rate of heart attacks and other organ failure. In the final weeks of life, the chickens often outgrow the ability of their legs to support them, making broken or otherwise failed legs endemic in the industry.

Photos of cage-raised chickens, borderline NSFW

Photos of broiler shed chickens, NSFW

Because it is cheaper to only change the litter between flocks it is a major source of bacterial infection and especially contact dermatitis (rashes and lesions on the chicken’s feet and lower body). It is common practice in the EU (not the US) to remove a portion of the flock a week before slaughter time to create enough space for the remaining birds to reach their usual slaughter weight, suggesting there isn’t much free space for the birds. Birds whose legs fail will often dehydrate to death. We don’t want to overegg this – a dead bird is an unproductive bird and only around 3.3% of the flock die during growth for any reason – but remember that this is a 3.3% chance of dying in only six or seven weeks.

De-beaking is common in broiler chickens (universal in laying chickens). One reason for debeaking is to reduce cannibalism which occurs because the birds are so stressed – pet chickens will peck each other to establish a dominance hierarchy but don’t kill and eat each other. Beaks are sensory and manipulative tools for chickens, so this is analogous to cutting the fingers of prisoners off without anesthetic to lower the probability of escape.

Shed chickens have it slightly better. They have a small amount of mobility, are able to do some natural activities such as socializing and digging in the dirt with their claws (but not usually their beaks) and have a little natural light from windows in the warehouse. On the other hand, chickens only cannibalize each other when very stressed and the strain on their systems from the massive growth they are forced to undertake causes considerable pain.

We think it is reasonable to say that broiler chickens exist in a state worse than death – in the model, we assume chicken-days are equivalent to -2 human-days (you’d rather have your life be 2 days shorter than have to experience a day of chicken life), but your intuitions may differ substantially.

2.2.2. Pigs

Pigs are the next-most commonly farmed food animal. There are two major sources of cruelty in pig production; the raising of the food-pigs themselves and the creation of new food-pigs from breeding pigs.

Breeding sows are confined to a ‘gestation’ or ‘sow’ crate for most of their lives. These are only slightly larger than their bodies, making it impossible to turn around or even lie down. Generally the floors are made of slats or iron rungs to allow manure to fall through. These slats can hurt the sensitive feet of the pigs, and the fact that they are confined directly above their own manure means they are exposed to ammonia toxicity, which leads to respiratory conditions common in confined sows (and presumably smells incredibly distressing). Pigs are highly intelligent, and the unstimulating confinement means that the pigs engage in repetitive stress behaviors such as biting at the metal bars of their cage – this can cause further harm such as mouth sores.

Shortly before birth, the pregnant sow is taken to a ‘farrowing crate’ – even more restrictive than a sow crate. This is designed to separate the mother from the piglet so the piglet can nurse without being crushed (piglets being crushed can happen in the wild, but it is rare – this is a problem almost entirely caused by the confined conditions the sow is kept in). The crate is so tight the mother cannot even see her baby once it is born, and the baby is taken away after about 17-20 days. The piglet is then prepared to be fattened for slaughter, and the mother is either re-impregnated and returned to the gestation crate or slaughtered herself if she is unlikely to survive another pregnancy.

Photos of gestation and farrowing crates, surprisingly SFW

Piglets being prepared for slaughter are castrated and have their tails docked, often without anesthetic. Unlike chicken beaks, pig tails don’t really seem to serve any purpose, but pigs show pain behavior towards their stumps suggesting that it is very sensitive even after being docked. The tails are docked to prevent other pigs biting it and causing an infection – again, behavior which is vanishingly rare in the wild and therefore seems to be a stress response to the conditions they are kept in. Piglets may also have their teeth clipped to prevent biting but we can’t find figures on how common it is. Pigs prepared for slaughter are kept in ‘finishing crates’ which seem to run from anywhere between a slightly larger sow crate (larger only in the sense that it is bigger – finishing pigs are much larger so don’t have any more space to turn around or express natural behaviors) and something a little more like a traditional farmyard pen but indoors – six or seven pigs confined to a small pen where they have just enough space to walk around if they want to.

Pig-tures of finishing crates, SFW

Pigs are highly intelligent animals, and when not confined to stalls will spend hours playing and rooting around in the mud. The pigs consumed for food will be in constant low-level pain and sows used for breeding will be in quite intense pain constantly. It is hard to imagine a more distressing event than having your child taken away from you or being taken away from your mother, and we might imagine that the constant lack of stimulus for both food and breeding pigs causes considerable boredom and sadness.

It is a harder call whether pigs exist in conditions worse than death. My intuition is that food pigs are right on the border, and breeding pigs would strongly prefer to not live. In the model we assume that a pig-day is worth -1 human days.

2.2.3. Cows

Cows are the only animals routinely farmed in conditions approaching the way people imagine farming to be in their head – that is, in a field where they have enough space to move around and socialize. Factory farmed cows spend six to twelve months being raised outdoors in fields (the sorts of cows you see dotted around the countryside), and are then transported to ‘feedlots’ for their last few months where they are fed an artificial diet of corn and soy that is very hard on their bodies and can cause illnesses such as ulcers. Note that almost all cow-meat can be labelled ‘grass fed’ because most cows spend their first year in fields eating grass: doesn’t mean that is where the majority of their final slaughter weight came from! Much like pigs, cows have complex social hierarchies and being put on a feedlot with thousands of other cows is depressing.

Beef cattle also endure individual painful events like castration, branding and dehorning (often done without anesthetic) and transport in cramped crates for long periods of time. It is unclear how to incorporate the impact of these events on the animal’s overall quality of life. We’d suggest animals raised on a field have the same quality of life as a traditionally farmed animal and animals raised on a feedlot have a quality of life moderately worse than a typical elderly human. By quite a long way cows appear to have it the best of all factory farmed animals and have lives that are clearly worth living.

We think we’d be pretty content to live as a cow in a field, but cows on feedlots seem to have lives that are closer to food-pigs. Approximately averaging these out over a cows’ lifetime, we model 1 human day as equal to 10 cow days. We can’t find good information on how sheep are factory farmed so we’ve assumed they’re just woolly cows for the purpose of estimating their quality of life.

2.2.4. Value of animal life

Quantifying and comparing subjective experiences of farmed animals is hard because there is no ‘natural unit’ of suffering or experience. We proceed instead by asking ‘at what factor are we willing to skip/trade off days of my life to live as any particular animal under factory farmed conditions’ as described above. Factory farmed cow lives seem greatly preferable to non-existence, pigs spend most of their time experiencing some form of chronic or acute suffering, and chickens have truly awful lives from birth to slaughter.

Slaughter itself may be a morally relevant part of valuing an animal’s life. In principle, animals are stunned before slaughter so that the process is painless (and evidence suggests animals are not distressed by watching other animals being stunned). However, in practice animals are often not insensible to pain when they are skinned or carved up, either because of poor training (paywalled WaPost link), religious beliefs around the way meat should be prepared (link, further figures) or just because of a culture of laxity and cruelty (INTENSELY NSFW link of animals being abused by slaughterhouse workers, SFW-ish PDF report of the investigation). ‘Ag gag’ laws and other efforts by farmers to avoid bad press prevent serious scholarly investigation of the extent of the issue, but the AnimalAid hidden camera investigation linked as a PDF above found evidence of criminally cruel treatment at one of the three abattoirs observed and evidence of mistreatment at another.

Also, some people believe in a specific ethical obligation to not kill conscious creatures that do not want to be dead, so that slaughter of even humanely stunned animals is immoral. We instead take the consequentialist view that there is a symmetric value in actualizing the existence of conscious creatures that want to be alive (again, a farmed animal’s practical alternative is non-existence).

In the model, we assume that at human-level consciousness the experience of a typical human life-day is worth the factory farmed experience of 10 cow days, -1 pig days, and -0.5 chicken days. We value a year of perfect health at $50,000 in line with typical healthcare priority setting in the US (it is much less in the UK and Europe – closer to £30,000), where a typical western life-year is about 86% of that ($43,000). Slaughter is not included as even the cruelest slaughter imaginable would be QALY-negligible if averaged over an animal’s whole lifespan.

3. What lives are worth living?

Speaking loosely, evolution does not care how happy your life is as long as you a) exist and b) pass on your genes, and so has come up with a number of ‘patches’ to the conscious reward system to ensure animals are never too satisfied to stop competing to breed but never so dissatisfied they would prefer to be dead. Instead, what we have is roughly a baseline set of happiness from which we deviate when good or bad things happen, but to which we almost always return to. If this is also true of animals then it does not matter that we perceive their lives as described above as intolerable; if we were actually forced to live as that animal then we would observe ourselves hoping we don’t die painlessly in our sleep. Since we cannot ask animals directly if they consider their lives worth living, we instead look at the conditions in which people report changes in happiness or commit suicide, and compare these to the lived experience of factory farm animals.

3.1. Habituation and Happiness Set Points

Habituation is a “decrease in response to a stimulus after repeated presentations.” The simplest form of learning, it is caused by neural processes that regulate responsiveness to different stimuli. When we are repeatedly sent a signal, especially if it is highly frequent and hasn’t recently changed in intensity or duration, we consciously experience it less acutely. This makes sense. If consciousness is about complex reflection, after we’ve already processed a signal and determined a response if any, the response becomes subconsciously automatic.

However, we don’t habituate just to local physical sensations, like the ticking of a clock or the pressure of a shirt against our skin. We habituate to pain and suffering as well, even to large shocks to the system. In the literature this is known as the disability paradox, whereby a majority of those with severe disabilities report having a good or decent quality of life, even when to external observers it seems like a life not worth living (although this story is nuanced, and some of the improvement is related to the ability of intelligent humans to adapt by changing their lifestyle).

Nevertheless, the consensus in happiness research is that people have a fairly stable general level of baseline happiness which they return to after certain large changes. In a famous study by Brickman (1978), paraplegics and lottery winners reported similar levels of happiness before and after what one might assume was a life-altering development, either extremely negative or extremely positive. And in a twin study of several thousand by Lykken and Tellegen, it was found that about 50% of variation in Well-Being scale of the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire is associated with genetic variation, and less than 3% (!) of the variance can be accounted for by any of socioeconomic status, educational attainment, family income, marital status, or religious commitment.

3.2. Lessons from suicide

Sometimes, humans decide that their lives are intolerable and commit suicide. Interestingly, we basically never observe this in other animals. The only maybe-credible anecdotal claims are of dolphins, which are highly intelligent and can commit suicide by not breathing (breathing by dolphins is probably an active choice, rather than an automatic process as regulated in humans by the amygdala).

This doesn’t mean we can conclude farmed animals prefer living because animals might lack the theory of mind or intelligence to act on their preference to stop existing. However, if humans in extremely poor conditions overwhelmingly do not choose suicide, we might infer that animal lives of roughly similar quality would also be worth living. Two well-studied areas where humans are placed in extremely poor conditions are slavery and terminal disease.

3.2.1. Slavery

The historical consensus is that while slavery caused extreme stress and suffering, the rate of suicide by black slaves was quite low. According to the 1850 U.S. census, slaves had a suicide rate of 0.72 per 100,000 while whites had a rate of 2.37 and freed slaves a rate of 1.15. From the Federal Writer’s Project Slave Narratives which documented incidences of resistance, only 1.2% were acts of suicide. Further, when slaves did resort to suicide, it was usually in response to deterioration in their circumstances or unfulfilled expectations, rather than being explained by living under the most brutal conditions – this is consistent with a ‘happiness set point’ theory.

To be clear, we are not saying that because enslaved Africans committed suicide at lower rates than free whites slavery wasn’t ‘that bad.’ There is a substantial academic literature explaining the cultural reasons for the difference. The observation is simply that the main explanatory factor of whether a slave thought it worth living was not how bad his or her life objectively was.

3.2.2. Terminal Patients

In a review of the psychological profile of patients in palliative care of 18,000 terminal cancer patients, a small number of which committed suicide, it was found that some of those who committed suicide:

“…presented functional and physical impairments, uncontrolled pain, awareness of being in the terminal stage, and mild to moderate depression… however, the loss of, and the fear of losing, autonomy and their independence and of being a burden on others were the most relevant.”

The presence of significant pain or even depression (what we might refer to as ‘objective suffering’) was not a significant factor in predicting suicide, the best revealed preference we have for whether a life is considered worth living by the morally relevant actor experiencing it.

3.3. What does this mean?

Preference for living is a strongly mean reverting process. The scientific literature and historical examples from slavery and terminal illness both suggest that humans will habituate to almost anything that is done to them. In our ancestral environment life was really, really hard. Brutally hard. And it makes sense that even in environments that modern folks would instantly label as ‘much worse than non-existence,’ evolution made sure that we would continue to have the strength of will to not only survive but want to.

How far does this go? Does this mean that animals, no matter how much suffering they experience, prefer living? Reasonable people can disagree. As detailed above, factory farmed animals – especially chickens – do not exist in anything remotely resembling an ‘ancestral environment’. Chronic stressors are more likely to cause permanent changes in happiness than acute changes, and, as in the case of chicken cannibalism absent food scarcity, it is likely that factory farming creates an environment that is not only unpleasant but one which even the astounding level of habituation we observe in humans might not adjust above the ‘worth living’ watermark.

In the model we take the habituation literature seriously, estimating by how much deviations from long-term set point of average quality of life (0.86) are neutralized by habituation. Based on the previous sections and how much worse factory farmed conditions are than an ‘ancestral environment’ in which habituation would be calibrated, we estimate that humans habituate by 80%, cows 70%, pigs 60%, and chickens 50%. Even though before we had assumed that we would prefer non-existence to being a factory farmed pig, and would dislike being a chicken twice as much, once habituation is taken into account pig lives are slightly better than non-existence, and chicken lives are quite bad but have a (negative) moral weight not much larger than the positive one of cows. However, since we consume so many chickens in the end they dominate the analysis.

4. Health Considerations

4.1. Nutrition

Animal protein sources such as meat, fish, eggs, and dairy contain a good balance of the 20 amino acids that we need for almost every metabolic process in the body, whereas individual plants are generally deficient in mix or concentration. The same is the case for micronutrients: animal protein sources are much higher in vitamin B12, vitamin D, the omega-3 fatty acid DHA, heme-iron and zinc.

Animal products provide most of the zinc in US diets, and meat, poultry, and fish provide iron in the highly bioavailable heme form. For example, the panel setting the new Dietary Reference Intakes recommends an 80% higher daily iron intake for vegetarians.

Concern also has been expressed about the difficulty that children have in obtaining adequate energy and nutrient intake from bulky plant-based diets. Dutch infants consuming vegan diets had poorer nutritional status and were more likely to have rickets and deficiencies of vitamin B-12 and iron, and the World Health Organization strongly recommends animal products for infants to ensure enough calcium, iron and zinc.

Whether or not a plant based diet is viable from a nutritional perspective depends mostly on whether you have the economic means to consume a wide variety of food sources, and may be riskier for small children or those whose ancestry is from regions where meat-eating was prevalent.

4.2. Long Term Health Outcomes

Estimating the long-term health outcomes of eating certain things is difficult because food is highly bound up in the culture we live in and culture correlates to just about every health outcome you could possibly imagine. Even less conveniently, nutritional science is highly anti-inductive; if a particular food group is identified as being healthy people with an interest in being healthy flock to that food group, and people with an interest in being healthy are likely to be healthy for a bunch of reasons regardless of diet.

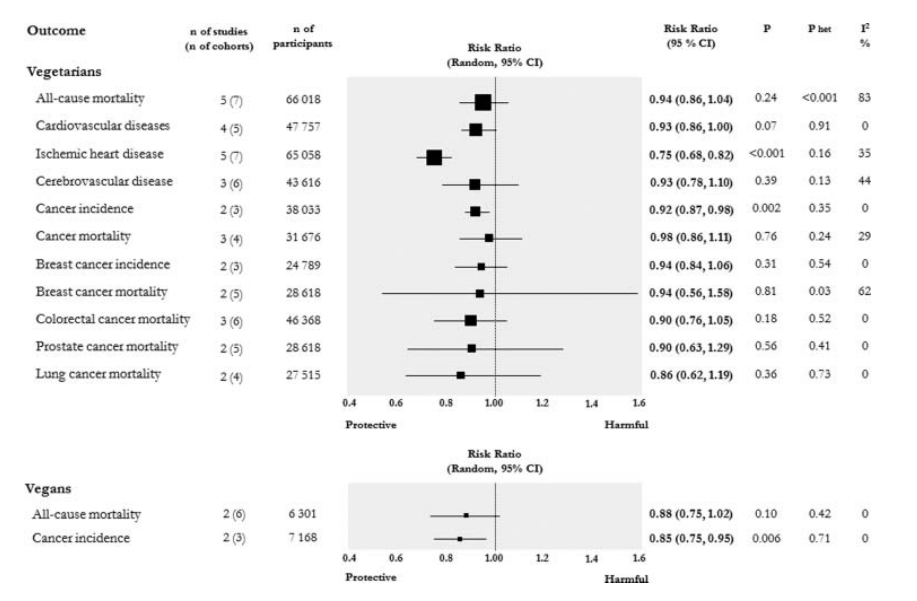

So here’s a nice headline result: vegetarians have less heart disease with extremely high certainty, and probably less cardiovascular disease and cancer too. Most of the studies in that meta-analysis have had some of the really obvious stuff adjusted away (race, income, etc.) but not all studies adjust for all confounders, and we should be cautious about trusting studies that ‘adjust for confounders’. If you ignore confounders then the answer is clear; eating vegetarian is good for you in every single way we can measure (including, possibly, circulating testosterone in defiance of stereotypes about meat eaters!).

If you are interested in confounders: There are a handful of cool natural experiments, taking groups with reasons to eat certain food but not bother with the associated healthy lifestyles, which are the closest we are likely to come to a true experiment in this area. In particular, the American Adventist Health Studies are pretty much state of the art in the field from what we can see. Adventists have quite unique dietary habits, brought about by religious prohibitions on certain foodstuffs which some Adventist churches follow and some don’t. Consequently, if you are an Adventist you are functionally ‘randomized’ into different food-eating conditions depending on which church you attend, and this randomization can be exploited by researchers.

If you are interested in confounders: There are a handful of cool natural experiments, taking groups with reasons to eat certain food but not bother with the associated healthy lifestyles, which are the closest we are likely to come to a true experiment in this area. In particular, the American Adventist Health Studies are pretty much state of the art in the field from what we can see. Adventists have quite unique dietary habits, brought about by religious prohibitions on certain foodstuffs which some Adventist churches follow and some don’t. Consequently, if you are an Adventist you are functionally ‘randomized’ into different food-eating conditions depending on which church you attend, and this randomization can be exploited by researchers.

Based on the Adventist Health Studies, a vegetarian diet increases life expectancy by around 3.6 years. The less meat you eat, the healthier your BMI and the less likely you are to get diabetes.

Overall we might expect lacto-ovo vegetarians to have a health related quality of life around 10% better than a meat eater, with most of this benefit being apparent 20 years after making the switch to a vegetarian diet.

You could complicate this picture a lot (especially by introducing future discounting) but we think the general principle that if you value life-years towards the end of your life you should likely go vegetarian is well demonstrated by the data:

One final point on how meat might affect your lifespan; there is a growing awareness of the fact that industrially produced meat is an ideal breeding ground for zoonotic disease, and that those diseases can mutate and jump to humans very quickly. Previous pandemics such as H1N1 (‘swine flu’) and H5N1 (‘bird flu’) may have originated with farmed animals, and were rapidly spread by the close contact of unhealthy animals and global nature of the meat supply chain. At the margin, eating meat probably increases the probability of a global pandemic but there isn’t good evidence on how much your individual consumption affects things at the margin.

One final point on how meat might affect your lifespan; there is a growing awareness of the fact that industrially produced meat is an ideal breeding ground for zoonotic disease, and that those diseases can mutate and jump to humans very quickly. Previous pandemics such as H1N1 (‘swine flu’) and H5N1 (‘bird flu’) may have originated with farmed animals, and were rapidly spread by the close contact of unhealthy animals and global nature of the meat supply chain. At the margin, eating meat probably increases the probability of a global pandemic but there isn’t good evidence on how much your individual consumption affects things at the margin.

In the model we take the Adventist study result at almost face value, estimating that eating vegetarian will increase your lifespan by 3 years, and include constant low costs due to possible nutritional deficiency and moderate benefits to health that appear later in life.

5. Environmental Impact

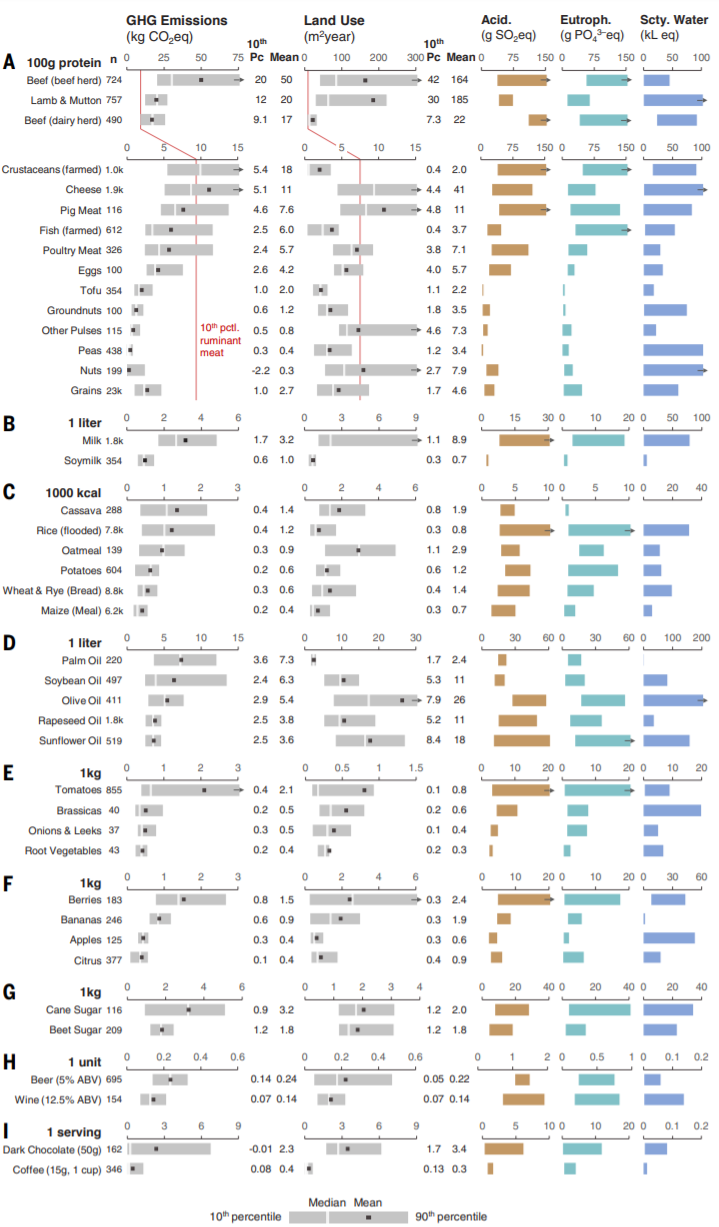

The environmental impact of meat consumption is difficult to measure and aggregate because the numbers are sensitive to the type of farming used and location, and any serious attempt requires a massive aggregation of different data sources. The best we could find was by Oxford’s Zoology department which combined data from 570 studies with a median reference year of 2010 covering 40,000 farms and 1600 processors, packaging types, and retailers, in 119 countries of 40 products representing ~90% of global protein and calorie use, focusing on five environmental impact indicators: land use, freshwater withdrawals weighed by local scarcity, greenhouse gasses, acidifying emissions, and eutrophying emissions.

Overall, today’s food supply chain creates ~13.8 billion metric tons of CO2 equivalents, which is about 26% of human caused emissions. It also causes 32% of global terrestrial acidification and 78% of eutrophication. It’s also very resource intensive, covering about 40% of the world’s ice- and desert- free land, and driving roughly 90% of global scarcity-weighted water use because irrigation returns less water to rivers and groundwater than industrial and municipal uses and predominates in water-scare areas and times of the year.

Because of different technologies and other environmental variables, the environmental impact of any foodstuff can vary widely. For example, ninetieth-percentile GHG emissions of beef are 105kg of CO2eq per 100g of protein, and land use (area multiplied by years occupied) is 370 m2 ∙year. These values are 12 and 50 times greater than 10th-percentile dairy beef impacts.

However, as you can see below the environmental impact from meat dwarfs that of other nutrition sources:

In total, meat, aquaculture, eggs, and dairy use ~83% of the world’s farmland and contribute 56-58% of food’s different emissions, despite providing only 37% of our protein and 18% of our calories.

In total, meat, aquaculture, eggs, and dairy use ~83% of the world’s farmland and contribute 56-58% of food’s different emissions, despite providing only 37% of our protein and 18% of our calories.

Because of substitution effects and nutritional requirements, it is unclear exactly how much of these resources would be freed up if we switched away from eating meat. In a simple model where we assume ‘protein is protein and calories are calories’ and freed up land would only remove carbon through natural vegetation and accumulated soil carbon, “moving from current diets to a diet that excludes animal products would result in reducing food’s land use by 3.1 (2.8-3.3) billion hectares (a 76% reduction), including a 19% reduction in arable land; food’s GHG emissions by 6.6 (5.5-7.4) billion metric tons of CO2eq (a 49% reduction); acidification by 50% (45-54%); 19 eutrophication by 49% (37-56%); and scarcity-weighted freshwater withdrawals by 19% (−5 to 32%) for a 2010 reference year.”

It’s difficult to translate these tradeoffs into ‘one number’ that captures the environmental impact of meat eating. Land which currently supports animal farming is likeliest to be least suitable for agriculture or urban dwellings, and the costs of climate change, the value of species diversity, and the future scarcity of freshwater are all difficult to measure.

One (very approximate) way is to assume that the human race is polluting the planet as much as it can sustainably (at current technologies it’s a lot worse, but we’re science-optimists), and that the long-term impact of a reduction in pollution is a proportionally inverse change in the equilibrium human population.

Water shortages, eutrophication, and acidifications are serious environmental concerns but can be managed. Greenhouse gas emissions and land seem like the most important constraints. Combining the statistics from the total absolute resource impact of the food supply chain with the relative impact of switching from meat-eating, we get that if the planet went vegetarian we’d reduce emissions by 12.5% and free up 30% of the world’s non-desert/ice land most of which we would not be able to immediately put to good use. We think it’s reasonable that the total reduction in ‘human pollution and resource use’ would be about 10%. Since raw resources and access to clean environment aren’t the only limiting factors on population size this result should be adjusted downward by a reasonable factor.

In the model, we assume that without meat farming there would be about 2.5% more capacity for population or quality of life, 30% of which (completely uneducated guess) would actualize as more lives, and 70% of which would actualize as better lives (and would count at 1/5th weight due to habituation).

6. Cost of Switching Diets

One good reason not to switch to a vegetarian diet would be if doing so was prohibitive, either because of the financial cost or the satisfaction from eating.

6.1. Cost per meal

In a trivial sense, vegetarianism is clearly cheaper. It takes more time and energy to grow plants that we feed to animals and then eat the animals than it does to just eat the plants themselves. This is borne out by research into the cost per calorie of various foodstuffs. Of course, humans don’t eat exactly the same food animals eat, and vegetarians are for some reason unwilling to just drink 2000 calories of canola oil every day.

The cost of various types of diet seem to be bizarrely under-studied (or perhaps crowded out by the literature on trying to get people to stop eating junk food). The one academic source I found seems to be really high quality though. Here is the paper and here is a nice associated blog post.

At all income levels meat eaters spend about $20 more per week than true vegetarians (~$1000 / year). Adjusting for all controls (including politics and body weight which may be affected by vegetarianism) reduces this number to a savings of $11.1/week, which is what we use in the model.

6.2. Psychological costs

However, one switching cost that might not be trivial is the psychological importance of having meat in your diet.

Most vegetarians eventually enjoy vegetarian food as much as meat (not sure if that’s just survivorship bias), but anecdotal experience from everyone I know who has gone vegetarian says that there is a really horrible period of adjustment of at least a couple years where you want to eat meat and can’t.

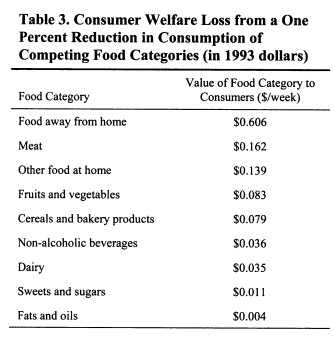

One reasonable measure of psychological pain is to look at how much people would be willing to pay to avoid it, which conveniently has been studied:

This table is the output of a point regression asking US consumers how much they would pay to avoid a one percent decrease in each category of food. A 1993 dollar is approximately half of a 2019 dollar (1.78), so consumers are saying that they would pay $15 per year to avoid a one percent reduction in their meat consumption. It is highly unlikely that people would accept one hundred times this value to cut out meat completely – it’s easy to cut out the first few percentage points of meat (just have slightly smaller portions) but gets harder as you are forced to make fundamental changes to your diet.

This table is the output of a point regression asking US consumers how much they would pay to avoid a one percent decrease in each category of food. A 1993 dollar is approximately half of a 2019 dollar (1.78), so consumers are saying that they would pay $15 per year to avoid a one percent reduction in their meat consumption. It is highly unlikely that people would accept one hundred times this value to cut out meat completely – it’s easy to cut out the first few percentage points of meat (just have slightly smaller portions) but gets harder as you are forced to make fundamental changes to your diet.

For those inclined to stop eating meat, we wouldn’t overthink this parameter. If the habituation literature has convinced you that you’d be just as happy in a wheelchair as a lottery winner then in the long-run you probably won’t mind eating more tofu.

In the model, we double the $1,500/year preference loss of meat implied by marginal preferences to $3,000 to account for social costs and elasticity of demand, and assume this decays to 0 by 10%/year as one gets used to the new lifestyle.

7. Conclusion

Overall, the case for reduced meat consumption is strong. Vegetarianism is cheaper, better for your health (if you can afford a diverse diet and are not an infant), and is less impactful for the environment. It also has a significant moral cost in terms of animal suffering.

At the outset of the collaboration the vegetarian was sure that farmed animals’ lives are so awful that the status quo is an unmitigated moral disaster; the meat eater was open to that conclusion but could also imagine being persuaded to spend all disposable income on buying meat and throwing it away because that was the only efficient means of causing the existence of sentient creatures who strongly prefer to exist. If you mapped reasonable conclusions on meat eating from a scale of -10 to 10, you could say that we started out as a confident -5 and highly uncertain 2, and ended up agreeing on a very confident -3.

Based on the research above, we’ve produced a ‘base case’ for the decision aid. It is weighted heavily towards the beliefs of the meat eater in the collaboration since the question revolves around what a ‘typical’ person might think and meat eaters are more ‘typical’ than vegetarians. We would certainly encourage you to tinker with the worksheet yourself though, as some decisions are very personal. You can download it here.

From the model we get that the total impact of meat eating per typical western consumer is roughly -$9,500 – that is, the ‘society of conscious beings’ would be better off by around $9,500 per year if any individual human meat eater switched to eating plants instead. To put this in other units, it would be about as good for 5 people to go vegetarian for a year as it would be for medicine to extend one person’s life by one year.

Each value in the table below represents the annual impact of a decision to eat meat versus eating an exclusively vegetarian diet. The right-most attempts to express everything in the same units ($) based on a willingness to pay for a year of perfect human life of $50,000 and a year of YOUR OWN life of $100,000 (to reflect the fact that people generally care about their own welfare more, but if you are a perfect utilitarian feel free to set these both to $50k!). Per the model we find that even though cows, sheep and (very weakly) pigs prefer farming to non-existence, the number of chickens eaten and the conditions they are farmed in dominates the ethical considerations. In terms of other harms, the impacts on your health and the environment are moderate, and the financial impact of switching to a vegetarian diet is small but negative – that is, the typical meat consumer will in the long run prefer to eat meat than spend the savings from vegetarianism elsewhere.

Human

life-year equivalents

Expressed

in $ equivalent

Annual

impact on other conscious creatures

Cows

0.009

$373

Pigs

0.007

$317

Sheep

0.002

$65

Cage

chicken

0.000

$0

Shed

chicken

-0.138

-$5,913

Fish

0.000

$0

Environ.

-0.027

-$1,166

Impact

on you

Health

-0.039

-$3,336

Finance

$162

TOTAL

LIFE YEARS

-0.186

-$9,498

Overall, the impact of eating meat like a typical person is likely to be substantially negative. Eating no chicken limits the impact on the animals themselves, but the harm to your own health and the environment outweighs the moral good you do by causing the creation of animals who are happy at the margin.

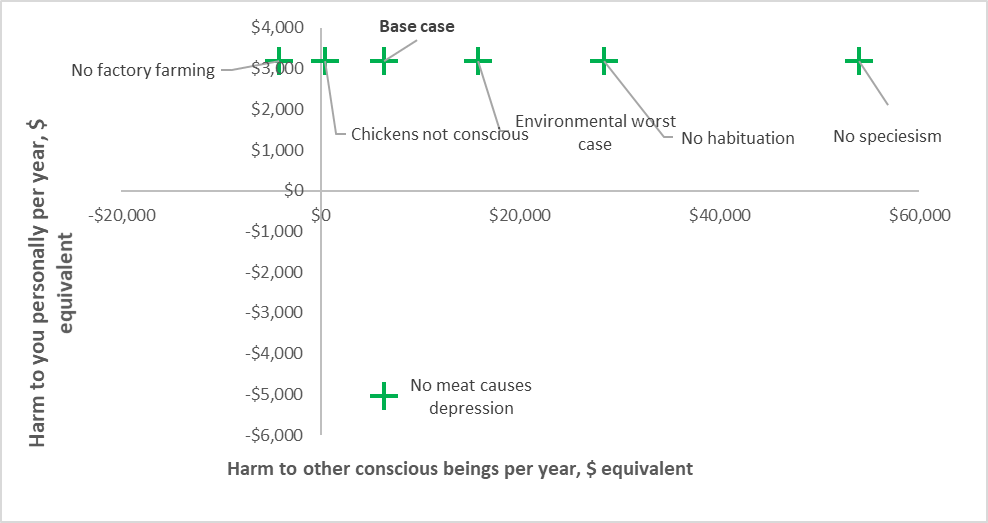

7.1. Sensitivity

The decision aid allows you to specify uncertainty over any of your estimates, which we have done anywhere we are still uncertain about the value of a parameter. This analysis is displayed in the graph below. For any plausible distribution of inputs meat eating is harmful to you personally, primarily for health reasons; and meat eating generally causes harm to other conscious creatures because of the impact on environment and the high suffering of chickens. However, there is significant uncertainty about this value; in a small number of cases eating meat actually produces benefit to society by creating more lives animals would prefer to live on net.

Another way of exploring model uncertainty is scenario analysis. We’ve calculated a number of scenarios that cover likely areas of disagreement.

Another way of exploring model uncertainty is scenario analysis. We’ve calculated a number of scenarios that cover likely areas of disagreement.

In order of least to most harmful to other conscious being, the scenarios are:

In order of least to most harmful to other conscious being, the scenarios are:

• No factory farming narrowly results in outcomes which favor eating meat, since every animal would prefer to be alive than not. The effect is not greater because there are still environmental and health implications to eating meat.

• Chickens not conscious – The base case assigns a 75% chance that chickens are conscious, and this is a big assumption to which the model is highly sensitive. Assuming chickens are not conscious results in outcomes which narrowly favor being a vegetarian, since the moral importance of creating worthwhile cow, pig and sheep lives is offset by the other harms of meat eating.

• Base case – As described in the document

• No meat causes depression – In this scenario not eating meat causes you a significant but not life-threatening illness – modelled by having minor depression (0.62 utility). This scenario is very interesting because it predicts that eating meat would be good FOR YOU, but would harm others, and therefore whether you should eat meat or not depends on the valuation you place on your own happiness versus the happiness of others (remember the model already values your QALYs higher than anyone else’s based on the assumption you are not a perfect utility maximizer AND you are compensated for the unhappiness meat causes).

• Environmental worst case – the resources used to create meat are the upper end of the plausible range (10%) and all of this resource will create new people. The more convincing you find the environmental argument the more likely you should be vegetarian

• No habituation – In this scenario no creatures (including humans) habituate at all, meaning they are exposed to the full ‘badness’ of the farming conditions. The less you buy the habituation literature, the more likely you should be a vegetarian; this is a very strong result

• No speciesism – In this scenario the value of conscious experiences for animals is weighted just as much as conscious experience for a human. This is the scenario that results in the strongest argument against eating meat, and could perhaps be the intuition driving the sometimes acrimonious state of discussion between meat eaters and vegetarians.

• Not shown in this analysis is an ‘Unfettered Vegetarian’ analysis, where the vegetarian collaborator is able to enter their own assumptions into the model without any check from the meat-eating collaboration partner. This is because what the vegetarian considers highly plausible assumptions (chickens are conscious, a much greater weight is placed on animal suffering/experience and much less habituation occurs) results in values that fall off the end of the graph – around $250,000 worth of harms to others per year.

Our key takeaway is that even under the most extreme scenarios we could think of meat eating is still very likely to be a net harm to both you and wider society. Also note that even in scenarios where you are not doing harm to both yourself and society, you are certainly hurting one of them quite a lot.

7.2. Impact on Collaborator Lifestyle

The meat eating collaborator was impressed by the environmental impact of beef and moral cost of factory farmed chicken. For the moment he has significantly reduced consumption of both, offsetting in part with salmon because fish have less environmental impact and are most likely not conscious.

The vegetarian was surprised how marginal the case for vegetarianism was when a ‘typical’ perspective was considered. Part of this is because he is still pretty skeptical that animals would actually habituate to the conditions we farm them in given the habituation literature doesn’t really cover conditions as cruel as factory farming. Another part might be that this collaboration has not focused on one-off traumatic events – especially slaughter – which probably don’t affect lifetime utility much but might be regarded as so self-evidently ‘evil’ that the way we have thought about the problem as a balance of good versus harm is incorrect. Having said that, although the actual harms of meat eating are less than he expected, the certainty of those harms occurring under any plausible distribution of beliefs (the fact that even a ‘typical’ person would probably regard meat eating as harmful considering everything) will probably make the vegetarian more militant about his vegetarianism. Sorry!

That being said, both collaborators agree that there is no substitute for evaluating the evidence for yourself. We can only hope that you find our analysis a useful reference.