Growth Mindset 3: A Pox On Growth Your Houses

[EDIT: The author of this paper has responded; I list his response here.]

Jacques Derrida proposed a form of philosophical literary criticism called deconstruction. I’ll be the first to admit I don’t really understand it, but it seems to have something to do with assuming all texts secretly contradict their stated premise and apparent narrative, then hunting down and exposing the plastered-over areas where the author tries to hide this.

I have no idea whether this works for literature or not, but it’s a useful way to read scientific papers.

Consider a popular field – or, at least, a field where a certain position is popular. For example, we’ve been talking a lot about growth mindset recently. There seem to be a lot of researchers working to prove growth mindset and not a lot working to disprove it. Journals are pretty interested in studies showing growth mindset interventions work, and maybe not so interested in studies showing they don’t. I’ll admit that my strong suspicions of publication bias don’t seem to be borne out by the facts here – see this meta-analysis – but I bet its more sinister cousin “all experimenters believe the same thing and have the same experimenter effects” bias is alive and well.

In a field like that, you’re not going to get the contrarian studies you want, but one way to find the other side of the issue is to look a little more closely at the studies that do get published, the ones that say they’re in support of the thesis, and see if you can find anything incriminating.

Here’s a perfect example: Mindset Interventions Are A Scalable Treatment For Academic Underachievement, by a team of six researchers including Carol Dweck.

The abstract reads:

The efficacy of academic-mind-set interventions has been demonstrated by small-scale, proof-of-concept interventions, generally delivered in person in one school at a time. Whether this approach could be a practical way to raise school achievement on a large scale remains unknown. We therefore delivered brief growth-mind-set and sense-of-purpose interventions through online modules to 1,594 students in 13 geographically diverse high schools. Both interventions were intended to help students persist when they experienced academic difficulty; thus, both were predicted to be most beneficial for poorly performing students. This was the case. Among students at risk of dropping out of high school (one third of the sample), each intervention raised students’ semester grade point averages in core academic courses and increased the rate at which students performed satisfactorily in core courses by 6.4 percentage points. We discuss implications for the pipeline from theory to practice and for education reform.

This sounds really, really impressive! It’s hard to imagine any stronger evidence in growth mindset’s favor.

And then you make the mistake of reading the actual paper.

The paper asked a 1,594 students from a bunch of different high schools to take a 45 minute online course.

A quarter of the students took a placebo course that just presented some science about how different parts of the brain do different stuff.

Another quarter took a course that was supposed to teach growth mindset.

Still another quarter took a course about “sense of purpose” which talked about how schoolwork was meaningful and would help them accomplish lots of goals and they should be happy to do it. This was also classified as a “mindset intervention”, though it seems pretty different.

And the final quarter took both the growth mindset course and the “sense of purpose” course.

Then they let all students continue taking their classes for the rest of the semester and saw what happened, which was this:

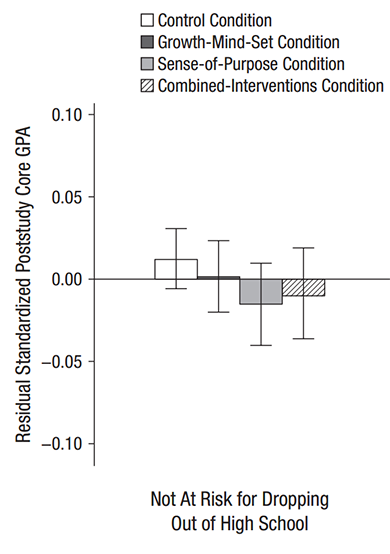

[EDIT: I totally bungled these graphs! See discussion of exactly how on the author’s reply above, without which the information below will be misleading at best]Among ordinary students, the effect on the growth mindset group was completely indistinguishable from zero, and in fact they did nonsignificantly worse than the control group. This was the most basic test they performed, and it should have been the headline of the study. The study should have been titled “Growth Mindset Intervention Totally Fails To Affect GPA In Any Way”.

[EDIT: I totally bungled these graphs! See discussion of exactly how on the author’s reply above, without which the information below will be misleading at best]Among ordinary students, the effect on the growth mindset group was completely indistinguishable from zero, and in fact they did nonsignificantly worse than the control group. This was the most basic test they performed, and it should have been the headline of the study. The study should have been titled “Growth Mindset Intervention Totally Fails To Affect GPA In Any Way”.

Instead they went to subgroup analysis. Subgroup analysis can be useful to find more specific patterns in the data, but if it’s done post hoc it can lead to what I previously called the Elderly Hispanic Woman Effect, after medical papers that can’t find their drug has any effect on people at large, so they keep checking different subgroups – young white men…nothing. Old black men…nothing. Middle-aged Asian transgender people…nothing. Newborn Australian aboriginal butch lesbians…nothing. Elderly Hispanic women…p = 0.049…aha! And the study gets billed as “Scientists Find Exciting New Drug That Treats Diabetes In Elderly Hispanic Women.”

As per the abstract, the researchers decided to focus on an “at risk” subgroup because they had principled reasons to believe mindset interventions would work better on them. In their subgroup of 519 students who had a GPA of 2.0 or less last semester, or who failed one or more academic courses last semester:

Growth mindset still doesn’t differ from zero. And growth mindset does nonsignificantly worse than their “sense of purpose” intervention where they tell children to love school. In fact, the students who take both “sense of purpose” and growth mindset actually do (nonsignificantly) worse than sense-of-purpose alone! But the control group mysteriously started doing much worse in all their classes right after the study started, so growth mindset is significantly better than the control group. Hooray!

Growth mindset still doesn’t differ from zero. And growth mindset does nonsignificantly worse than their “sense of purpose” intervention where they tell children to love school. In fact, the students who take both “sense of purpose” and growth mindset actually do (nonsignificantly) worse than sense-of-purpose alone! But the control group mysteriously started doing much worse in all their classes right after the study started, so growth mindset is significantly better than the control group. Hooray!

Why would the control group’s GPA suddenly decline? The simplest answer would be that by coincidence the class got harder right after the study started, and only the intervention kids were resilient enough to deal with it – but that can’t be right, because this was done at eleven different schools, and they wouldn’t have all had their coursework get harder at the same time.

Another possibility is that sufficiently low-functioning kids are always declining – that is, as time goes on they get more and more behind in their coursework, so their grades at time t+1 are always less than at time t, and maybe growth mindset has arrested this decline. This is plausible and I’d be interested in seeing if other studies have found this.

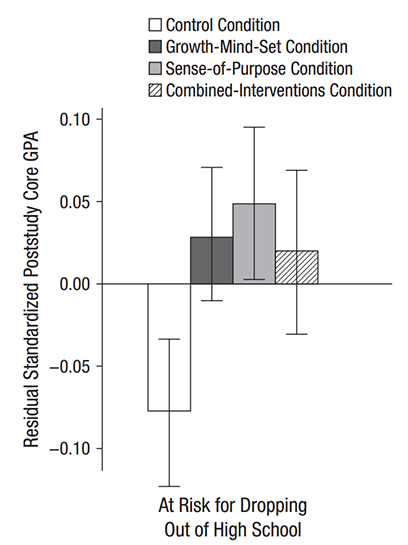

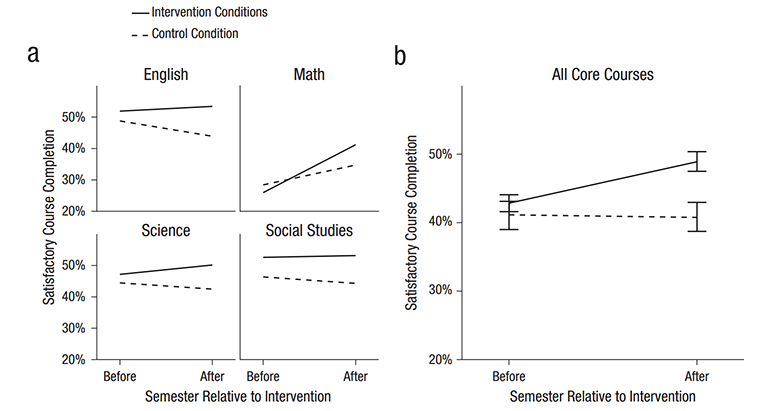

Perhaps aware that this is not very convincing, the authors go on to do another analysis, this one of percent of students passing their classes.

This is the same group of at-risk students as the last one. It’s graphing what percent of these students pass versus fail their courses. The graph on th left shows that a significantly higher number of students in the intervention conditions pass their courses than in the control condition. This is better, but one part still concerns me.

This is the same group of at-risk students as the last one. It’s graphing what percent of these students pass versus fail their courses. The graph on th left shows that a significantly higher number of students in the intervention conditions pass their courses than in the control condition. This is better, but one part still concerns me.

Did you catch that phrase “intervention conditions”? The authors of the study write: “Because our primary research question concerned the efficacy of academic mindset interventions in general when delivered via online modules, we then collapsed the intervention conditions into a single intervention dummy code (0 = control, 1 = intervention).

We don’t know whether growth mindset did anything for even these students in this little subgroup, because it was collapsed together with the (more effective) “sense of purpose” intervention before any of these tests were done. I don’t know if this is just for convenience, or if it is to obfuscate that it didn’t work on its own.

[EDIT: Scott McGreal looks further and finds in the supplementary material that growth mindset alone did NOT significantly improve pass rates!]

The abstract of this study tells you none of this. It just says: “Mindset Interventions Are A Scalable Treatment For Academic Overachievement…Among students at risk of dropping out of high school (one third of the sample), each intervention raised students’ semester grade point averages in core academic courses and increased the rate at which students performed satisfactorily in core courses by 6.4 percentage points” From the abstract, this study is a triumph.

But my own summary of these results, as relevant to growth mindset is as follows:

For students with above a 2.0 GPA, a growth mindset intervention did nothing.

For students with below a 2.0 GPA, the growth mindset interventions may not have improved GPA, but may have prevented GPA from falling, which for some reason it was otherwise going to do.

Even in those students, it didn’t do any better than a “sense-of-purpose” intervention where children were told platitudes about how doing well in school will “make their families proud” and “make a positive impact”.

In no group of students did it significantly increase chance of passing any classes.

Haishan writes:

If ye read only the headlines, what reward have ye? Do not even the policymakers the same? And if ye take the abstract at its face, what do ye more than others? Do not even the science journalists so?”

Titles, abstracts, and media presentations are where authors can decide how to report a bunch of different, often contradictory results in a way that makes it look like they have completely proven their point. A careful look at the study may find that their emphasis is misplaced, and give you more than enough ammunition against a theory even where the stated results are glowingly positive.

The only reason we were told these results is that they were in the same place as a “sense of purpose mindset” intervention that looked a little better, so it was possible to publish the study and claim it as a victory for mindsets in general. How many studies that show similar results for growth mindset lack a similar way of spinning the data, and so never get seen at all?