[ACC Entry] Should Transgender Children Transition?

[This is an entry to the Adversarial Collaboration Contest by flame7926 and a_reader.]

[Content note: suicide, depression, transphobia, self-harm]

Transgender childhood transition is a hotly debated topic, with extensive media coverage devoted to it in recent years. (pro: BBC, The Lancet and The New York Times ; contra: The Cut, New Statesman and The Globe and Mail). We see plenty of stories of transgender children (or gender dysphoric children and gender nonconforming children), both in the media and in the blogosphere. As early as 2 or 3, defying the expectations of their family, those children show a persistent and insistent preference for many things associated with the other sex: little boys want long hair and love dresses, Barbie dolls, Disney princesses and mermaids; little girls, instead, dislike stereotypically feminine activities and prefer rough and tumble play, refuse to wear dresses and insist to have their hair shorter and shorter.

Sometimes, from the very beginning, the toddler corrects the parents: “I’m a boy /girl!”, but more frequently cross-gender behavior is more prevalent. This is only sometimes followed with the child expressing preferences that would be termed gender dysphoria. The child (born and currently living as a as one sex) says to their parents something like “God made a mistake” or “something went wrong in Mommy’s tummy” because he should have been a girl, not a boy (or the other way around). The worried parents search information on the internet and seek out the advice of an expert. There, they usually find one or both of these contradicting opinions:

Gender-affirming approach

Listen to your child – he/she knows best his/her gender. Let your child be his/her true self. It’s your responsibility as a parent to support your child in all stages of his/her transition: social transition now, puberty blockers at the beginning of puberty, cross-sex hormones in adolescence, surgery at 18. To oppose it is child abuse. Transphobia costs lives: 41% of transgenders attempt suicide. Do you prefer a happy daughter or a dead son?

Or:

Therapeutic approach

Your child is just confused. He/she is too young to understand gender and to take such important decision. 80% of gender nonconforming children desist. You, as a parent, have the responsibility to correct his/her wrong behavior. If you tolerate it, gender dysphoria will be reinforced by repetition and persist to adulthood. To encourage your child’s delusion is child abuse. Transgenders individuals face lifelong struggle and often suffer from poor mental health: 41% of transgenders attempt suicide. Do you really want that for your son, when he could instead come to accept the body he was born with?

The first approach is promoted by transgender activists, the second by the conservative media, but both are supported by some experts. The “Gender-affirming approach” is supported by the Dutch team from the Gender Clinic at VU Medical Centre, Amsterdam, who elaborated the typical transition treatment for minors, with puberty blockers at 12 and cross-sex hormones at 16, and, in the US, by Kristina Olson and others from the TransYouth Project. The “Therapeutic approach” is supported by Kenneth Zucker and his team from the Gender Identity Service at Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, and, in the US, by Paul McHugh at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. There are also experts such as Debra Soh, once a gender nonconforming girl herself, that advise parents to wait and see until adolescence, because in many cases gender dysphoria desists spontaneously, without intervention.

Who to believe when the experts disagree? Let’s see the evidence.

What is Gender Dysphoria/Gender Identity Disorder?

Children labeled transgender are usually diagnosed with Gender Dysphoria (as per the DSM-V), previously known as Gender Identity Disorder (in DSM-III through DSM-IV-TR). DSM refers to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders published by the American Psychiatric Association – DSM-III was published in 1980, with a revision in 1987, DSM-IV published in 1994, with a revision in 2000, and DSM-V coming out in 2013.

According to the APA as per DSM-V, “gender nonconformity is not in itself a mental disorder. The critical element of gender dysphoria is the presence of clinically significant distress associated with the condition”. Both Gender Identity Disorder and Gender Dysphoria include a desire to be or insistence that they are a gender that does not match their biological sex. This desire has to be strong and persistent and is usually accompanied by a preference for clothing of the opposite gender, cross-gender toys, games, and stereotypical activities, as well as the assumption of cross-gender roles in play. It may be accompanied by a discomfort or dislike of their current sexual anatomy and a desire for the sexual anatomy of the opposite sex. GID was said to “cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning”, while GD is merely “associated with” similar distress or impairments.

Gender and Sex Difference

Transgender refers to an individual gender identity that doesn’t correspond to the sex or gender they were born with, while gender dysphoria is a psychiatric diagnosis that refers discomfort with one’s physical or assigned gender. Individuals can have or previously have had gender dysphoria without identifying as transgender, while the most (but not all) transgender individuals should fall under the gender dysphoric label according to experts.

Based on the balance of the evidence, both social transitioning and puberty blockers should be approached with caution. There is moderate evidence that social transitioning improves mental health outcomes, and from a perspective concerned with validation of trans-identities it is important. But there are few studies on the long-term effects of social transitioning on rates of persistence and desistence (the number of children who remain gender dysphoric as they age).1 Similarly, puberty blockers may have negative physical health consequences, including an effect on bone-density, though a positive effect on mental health. Still, these choices should be made by families in consultation with experts. Individuals should develop a position on the topic with full awareness of the evidence and taking into consideration their preexisting biases and exposure to social norms on the topic.

Gender Identity Disorder and Gender Dysphoria in Youth

Gender dysphoria in youth is uncommon, with estimated prevalence of around 1%. Acceptance of transgender individuals is relatively low, with 30% of Americans saying they hold somewhat unfavorable or very unfavorable views of transgender individuals. 41% of parents also would be either “very” or “somewhat” upset if their child was transgender. Due to the lack of acceptance of gender dysphoric behavior and identities, it is possible that many gender dysphoric youth go unaccounted for. Gender dysphoria also doesn’t have a perfect overlap with being transgender, as some children feel uncomfortable with the gender that corresponds to their biological sex but don’t necessarily identify as the other gender.

According to Zucker et al. (1993), in a gender identity interview for children, when asked if they are a boy/girl, most (79 out of 85 gender nonconforming children) respond with their biological sex and not the other gender. Yet 30 out of 85 say they sometimes feel more like a boy than a girl (or reverse). Gender dysphoria is associated with feelings that their biological sex is not correct but is not perfectly correlated with such feelings.

According to the APA, treatment options for gender dysphoria include, “counseling, cross-sex hormones, puberty suppression and gender reassignment surgery.”

Desistence

Desisting is the term used to refer to children and youth who previously expressed gender nonconformity (as defined by the gender dysphoria/gender identity disorder diagnosis within various editions of the DSM manual) and are no longer gender dysphoric.

Brief disclaimer – Desistence is a fraught term and has been used to “denote the cessation of offensive or antisocial behavior“. It is difficult to extract the term from its historical context of use in which a transgender life was deemed a less preferred outcome. Yet it is relevant to the discussion and is the term used in papers which study the topic and thus we will use it here, aware of its potentially problematic implications.

The existence of desisting as a concept is debated by some who say that it diminishes the validity of transgender youth identities by painting dysphoric gender feelings as a choice or a phase that one may grow out of – while others claim flawed methodologies in studies purporting high numbers of desisting youth. (Julia Serano, Temple Newhook et al. (2018)). Yet it remains hard to deny that some fraction of individuals who previously expressed these feelings as youth do not anymore as adults.

Desistence matters because any recommendation for gender dysphoric youth, whether it be social transitioning, puberty blockers, or other treatment, may affect those who end up desisting from their dysphoria as well as those for whom the dysphoria persists.

Additionally, papers such as Temple Newhook et al. (2018) and Olson (2015) argue against the narrative of transgender childhood desistance (including the commonly cited figure that 80% of children desist), claiming methodological errors in the original studies. They argue that these studies (including Steensma et al. (2011 and 2013), Drummond et al. (2008), and Wallien and Cohen-Kettenis (2008) – all discussed below) conflate gender non-conforming children and truly gender dysphoric and transgender children. While most of these studies include samples that have both threshold (GD or GID diagnosis) and subthreshold children, the results are separable by diagnosis. These papers additionally critique the Steensma et al. and Wallien and Cohen-Kettenis studies for including non-respondents among desisters, but this is again separable in data analysis.

Temple Newhook et al. (2018) continue to point out that many of the children involved in the studies, (at the Amsterdam and Toronto clinics) were enrolled in programs to reduce likelihood of GD persistence, or at least not supported socially in expressing their identities – and that these were in and of themselves interventions which could affect results. Yet as Zucker (2018) contends, there is no neutral way to approach transgender youth – everything may affect persistence and desistence rates.

We acknowledge these criticisms of the body of research on gender dysphoric desistance, which, while weakening the strength of the evidence, does not invalidate it. Some children who express a range of desires that can be seen as comprising a transgender identity (up to and including identifying as the other gender) do not continue to hold this identity as they pass through puberty.

Many of these individuals who do not continue to feel gender dysphoria do identify as homosexual or bisexual. According to one study, half of the boys in the desisting sample were homosexual or bisexual, while 24% of a total sample of gender dysphoric youth (both threshold and subthreshold) were bisexual or homosexual in behavior.

Desistence Statistics

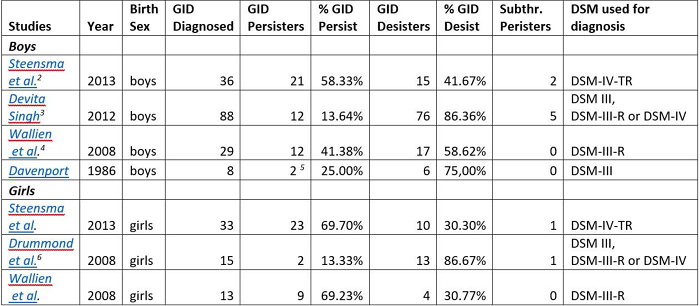

Statistical evidence supports the case that somewhere close to or above 50% of children with GID or GD diagnoses subsequently desist and do not express these feelings past puberty. To respond to criticisms of these studies, we differentiate between those diagnosed with GID or GD (see table above) and those who express gender-nonconforming behaviors but are subthreshold according to the diagnosis. All studies found at least 30-40% of diagnosed children desist, with the percentage as low as 30% in natal girls and 41% in natal boys in the Dutch studies (not counting non-responders), but as high as 75-86% in an unpublished thesis (Singh 2012) and 2 small studies (Drummond et al. 2008, Davenport 1986).

Statistical evidence supports the case that somewhere close to or above 50% of children with GID or GD diagnoses subsequently desist and do not express these feelings past puberty. To respond to criticisms of these studies, we differentiate between those diagnosed with GID or GD (see table above) and those who express gender-nonconforming behaviors but are subthreshold according to the diagnosis. All studies found at least 30-40% of diagnosed children desist, with the percentage as low as 30% in natal girls and 41% in natal boys in the Dutch studies (not counting non-responders), but as high as 75-86% in an unpublished thesis (Singh 2012) and 2 small studies (Drummond et al. 2008, Davenport 1986).

Steensma et al. included a sample of 80 youths formerly diagnosed with GID as children at the Amsterdam gender clinic. Of these formerly GID children, 58.3% persisted of (biological) males persisted past childhood, excluding both non-responses and responses by parents. 69.3% of females persisted past childhood. If non-responses are included (and Steensma et al. make an argument that they should count as desisters since the clinic in question is the only gender and sexual identity clinic in the Netherlands), then 48.5% of males persisted and 62.2% of females persisted.

While the most cautious estimate of desistance figures from this data is 41.7% of males and 30.7% of females, this is still a substantial number of children who previously had exhibited full GID traits who ceased to at some point before adulthood.

Wallien and Cohen-Kettenis (2008) examined a sample of 77 children, with 58 of them formerly GID and 19 subthreshold. 21 of these children persisted and 33 desisted, with 23 non-responses. If only GID children are included, then 50% of the individual male respondents persisted and 50% desisted, while for females 75% persisted and 25% desisted. If parental responses are included as well then the desisting percentages are 59% for males and 41% for females.

This study adds to the body of evidence that a not insignificant number of children with full GID diagnoses who respond to the questionnaire do desist from these feelings at a later point.

Drummond et al. (2008) examined 25 gender non-conforming girls, including 15 girls with GID diagnoses and 10 that were subthreshold. At follow-up (mean age of 23.24 years), three of them still had gender dysphoria. Two of these were from the fifteen girls with a GID diagnosis, giving a desistance rate of 86.6%. Singh’s unpublished thesis (2012) echoes these results, with 76 out of 88 formerly GID participants at follow up having desisted, for a rate of 86.4%.

Though Drummond et al.’s small sample size and the unpublished nature of Singh’s work provide limitations for the interpretability of these two studies, the low percentage of persisters among their results do provide some force to their evidence.

Some additional studies from before 2000 yield similar results with small (less than 20) sample sizes, including Davenport (1986), Zuger (1978), and Lebowitz (1972). While the applicability of these studies is diminished because of the length of time that has passed since their creation and the changes in understanding of gender and sexuality since then, they do still provide some evidence that children’s gender identities change as they age.

Overall, it is clear that at least 25% of children with GID diagnoses desisted, and probably closer to/upwards of 50%. These are not insubstantial numbers of children who previously experience a great deal of distress at their natal sex and do not anymore.

Qualitative research also provides important information about desisters, and particularly on differentiating factors between those who will desist from their gender dysphoria from those who will persist in it and/or eventually undergo sex-reassignment treatment. This research indicates that children who persist generally have stronger gender dysphoric feelings to begin with, including a stronger aversion to their physical anatomy and more insistent they were the other sex as opposed to only wishing they were. For example, “The persisters explicitly indicated they felt they were the other sex, [while] the desisters indicated that they identified as a girlish boy or a boyish girl who only wished they were the other sex”.

Puberty additionally proved decisive for both desisters and persisters, as it was the time when their gender dysphoric feelings either weakened or intensified. Singh (2012) adds that differences in DSM criteria for children as opposed to adolescents and adults for GID/GD may lead to diagnoses of some children who are not what would be considered gender dysphoric in adulthood. Wallien and Cohen-Kettenis additionally differentiate persisters from desisters by their GIIC and GIQC scores (two questionnaires about gender non-conforming behavior and identity) with persisters on average having significantly higher scores according to these measures.

Yet, neither the strength of cross-gender feelings nor a GID/GD diagnosis are perfect indicators of whether individuals will later identify as transgender or not, as even some subthreshold children persist and are transgender (8.7% of males and 4.2% of females, according to Steensma et al. (2013)). Thus, some differentiating factors are identified such as the strength of gender dysphoria, a gender dysphoria diagnosis, and actual feelings of being the other sex rather than simply wishing one is, but for the most part it is difficult to tell which children will continue feeling gender dysphoric as they pass through puberty into adulthood.

Narratives of Desisting

Nonetheless, there are a wide variety of examples of children who previously expressed varying degrees of gender dysphoric feelings and do not anymore. These children range from those who simply had cross-gender preferences in toys or play to those who felt they were the other gender, and even to those who began cross-sex hormones.

Some children express feelings of gender dysphoria when very young and the strength of these feelings lessen as they grow older. One such case is C.J., who used to draw himself as a girl. He played with dolls and liked “pink, purple and princesses”. At 4, he said he was going to be a woman when he grew up. At 6, he asked his parents to call him Rebecca and “her” (but after a while renounced, not feeling comfortable). Some professionals advised his mother to transition him socially, but the mother trusted her “mom guts” more. Now, at 11, C.J. writes “I feel like I’m a different type of boy. But I’m a boy for sure.” and when a friend transitioned he said he “couldn’t imagine being a girl every day“. “I do remember wanting to be a girl if I think about it really hard,” he adds, “but I don’t want to be a girl anymore”. Although still visibly gender nonconforming – or gender creative, as his mother prefers to say – the child grew into a more fluid identity in a way in which he became more accepting of the gender that corresponds with his natal sex.

Some other children express various degrees of gender dysphoria and then unexpectedly desist during puberty. Among these people is neuroscientist Debra Soh, who as a child was strongly opposed to feminine pastimes and playmates, and even urinary positions. Yet when she reached her late teens, “the idea of appearing feminine no longer repulsed [her]“. Even the strongest feelings of dysphoria can sometimes subside: in a BBC documentary, “Transgender Kids: Who Knows Best“, a girl named Alex remembers that she “wanted to be a boy” in childhood, while her father remembers her screaming “I’m a boy! I’m a boy!” Now she feels like a regular girl and presents in a feminine manner. The change happened at 12. In rare cases, it can happen even after social transition: Susie Green, chair of the UK transgender charity Mermaids, reports a second-hand account of the son of the former Mermaids chair, who “lived as a girl for three years… [then] when he realised that he was not female, he simply changed back.” For these children, the time and changes associated with puberty seem to be a deciding factor in whether they will desist or persist with their gender dysphoria. Their feelings were lengthy and lasting, yet changed as they reached and passed through puberty.

The most unusual case is that of an Australian boy named Patrick Mitchell, who was diagnosed at 12 with gender dysphoria. According to an Australian news site, Mitchell was, “Increasingly unhappy, suffering panic attacks and verging on depression, he told [his mother] if he could not go on puberty blockers he would run away and get them himself, or kill himself.” He took puberty blockers, then switched to estrogen (prescribed to his mother, because he was too young to obtain it legally) and started to grow breasts. But at 14, he changed his mind when he began to socially transition: “Teachers at school began to refer to him as a girl which triggered Mitchell to question if he had made the right decision”. This is another instance where puberty plays a role in determining what sex an individual feels comfortable as, physically.

Overall, these narratives show that gender identity is sometimes fluid and remains fluid through adolescence. Children may at one point be adamant they are the gender of their non-natal sex, yet later identify as the gender of their natal sex. Yet this does not give us reason to doubt these children’s’ sincerity or the validity of their identities at any point – but simply recognize that they can possibly change in the future, through no choice of the child.

Mental health and Social Transitioning

One of the primary factors in favor of increased support and validation for transgender children (which can include social transitioning and agentive decision making regarding puberty blockers) is the extent of mental health issues faced by children, youth, and adolescents with gender dysphoria. This includes an elevated risk of suicide, anxiety, and depression for transgender youth and adults. Additionally, sex reassignment doesn’t alleviate all negative mental health associations of transgender identities. Yet there is also a growing body of evidence showing that increased family support and allowing social transitioning does have mental health benefits, though the strength of these is up for debate.

Rates of depressive and anxiety symptoms are elevated among the transgender community, with 51.4% of women and 48.3% of men having depressive symptoms, and 40.4% of women and 47.5% of men having anxiety symptoms [sample size 351] (Budge et al. 2013). Grossman and D’Augelli (2007) additionally found that out of 55 transgender youth (ages 15-21), 45% had suicidal ideations and 26% had a history of life-threatening behaviors. Children diagnosed with Gender Identity Disorder also had a significantly higher rate of anxiety according to reported negative emotions and skin conductance level (though not in cortisol or heart rate) – a sample which included 25 GID children and 25 age-similar controls from the Netherlands of which 36% of the GID children reached a clinical threshold for internalizing problems. Finally, Haas et al. (2014) found that out of over 6000 transgender and gender non-conforming respondents, there was a suicide attempt rate of 41% against a population average of 4.6% – and over a dozen surveys found between 25% and 43% suicide attempts among the trans community.

There is additionally evidence that sex reassignment doesn’t alleviate all negative mental health associations of transgender identities. (Dhenje et al. 2011). Out of a sample of 324 sex reassigned persons in Sweden, there were significantly higher than rates of mortality, suicide, and psychiatric morbidity among transsexual individuals than among the general population.

Social Transitioning

Social transitioning (presenting socially as the gender of your non-natal sex, including using different pronouns, dressing differently, and appearing as the opposite gender) has been proposed by some (including Olson et al. 2016 in Pediatrics) researchers and therapists as a means of addressing the gender dysphoric desires of children with gender dysphoria. Many children express a desire to be or present as the other gender. Validating these desires and allowing them to present as the gender of their non-natal sex may help them feel more comfortable in their body.

Yet others including leading childhood gender dysphoria researchers (see Zucker 2018) believe that social transitioning may increase the chance that gender dysphoric feelings persist into adulthood. Given that gender dysphoria is associated with uncomfortableness with one’s body as well as anxiety, depression and an increased rate of suicide, some posit that on the whole it would be better if children lost these feelings as they grew older. Others claim that a preference for desistence is transphobic and reminiscent of conversion camps and other psychotherapy methods that attempt to erase gay and trans identities.

There is a lack of evidence for the long-term effects of social transitioning. According to the studies on mental health though, family support and affirmation of identities can decrease the risk of mental health problems in gender dysphoric and transgender youth and adults. For example, social support and transition status decreased anxiety and depression, while transition status was negatively related with the same. Suicide attempters have reported more physical and verbal abuse from parents, while strong family relationships decreased the suicide rate (from above 50% with less contact and acceptance from family to 33% when family relationships remain strong). Olson et al. (2016) additionally found that social transitioning for children (73 sample size with two controls) led to them having typical rates of depression with only slightly elevated rates of anxiety – though these were measured through a parent proxy questionnaire. A similar study on trans children using age-similar and sibling controls found that when socially transitioned, they had normal rates of depression and only slightly elevated rates of anxiety – which differs from results found with non-socially transitioned trans youth.

There is no evidence yet that social transitioning increases the rate that gender dysphoria persists or desists.

Children are often the driving force behind social transitions, though the extent to which the possibility of social transition is considered in the first place is affected by family support and media exposure is debatable. For example, one mom reports that, “when he was six and asked us to call him by a girl’s name and use female pronouns.” An eight-year-old child took the initiative and, “sent an email to everyone at her primary school saying she was a girl trapped inside a boy’s body. After that, she started going to school dressed as a girl.”

Even as young as kindergarten, children are expressing desires that they are the other gender and would like to be identified as such. One parent tells a story of their child lining up for class: “That morning, they’d divided the kindergartners into two lines, boys and girls – and Coy had lined up with the girls. “You’re a boy,” the teacher had corrected. Coy had sobbed for the rest of the day. Even my teacher doesn’t know I’m a girl!” he wailed.” A three-year-old child expressed the idea that they, “[were] supposed to be born a girl, but [were] born a boy instead“. This child subsequently wanted to switch pronouns and change their name around a year later. These narratives support the idea that children do know and can express their desires regarding social transitioning (though these desires may change later).

There is additionally some evidence that social transitioning can serve as a tool to differentiate individuals on the strength of their cross-gender identity. For instance, one anecdotal account from a mother indicates that a child has expressed transgender desires and decided to socially transition and was supported in this decision, but didn’t feel comfortable as the opposite gender and transitioned back.

One argument against social transition is that some children find it difficult to transition back to presenting as the gender corresponding to their natal sex. Though this varies based on the individual situation (see desistance narratives for examples of children who had minimal issue transitioning back), Steensma et al. (2011) found that some girls, who were almost (but not even entirely) living as boys in their childhood years, experienced great trouble when they wanted to return to the female gender role”.

Overall, the evidence concerning social transition is mixed, with medium sized positive mental health effects present, but unknown consequences on the child’s future gender identity and dysphoric feelings as well as possible difficulty transitioning back.

Social Constructions of Gender and Samoa

Evidence of better outcomes for those with larger amounts of social support may indicate that mental health problems (primarily anxiety, depression, and increased risk of suicide) associated with transgender and gender dysphoric individuals are more due to society’s treatment of transgender individuals than due to gender dysphoria itself.

For an example of this theory in action we turn to Samoan culture, where a cross-gender identity (termed fa’afafine) is accepted and treated as normative. This study (Vasey and Bartlett 2007) examined whether Samoans with cross-gender identity (Fa’afafine) experience the same distress about gender identity that individuals in Western locales do. Fa’afafine are men who generally present as feminine and are almost exclusively sexually attracted to other men. The authors say that, “Most self-identify as fa’afafine, not as men. A minority self-identify as women”. They do not identify as gay or homosexual even though they almost exclusively are sexually attracted to other men.

The study examined 53 fa’afafine adults and 51 controls from similar Samoan contexts about their childhood behavior. It asked them whether they recalled, “(1) a strong and persistent cross-gender identification in childhood; (2) a sense of inappropriateness in the male-typical gender role; (3) a discomfort with their sex; or (4) distress associated with any of the above.” Most fa’afafine remember engaging in female-typical behaviors as children and no distress related to this behavior. Many believed they were girls as children and also don’t remember any distress about these feelings. They do remember negative feelings toward male roles and typical male activity as children, while some had negative feelings towards their genitals as children.

According to the authors of the study, we can assume many of children would have had GID as defined by DSM-IV-TR. Yet, these individuals do not remember distress about expressions of cross-gender identity. A small number do remember distress with their genitals. Similarly, fa’afafine do not report higher rates of bullying or victimization due to physical aggression.

This study of another cultural context provides evidence that transgender identity is a cultural-context dependent phenomenon, and that distress (and associated mental health problems) faced by transgender individuals are related to their treatment within society rather than to gender-atypical behavior and identity itself.

Puberty Blockers

Puberty blockers are another aspect of the youth gender transition process which is hotly debated. Adolescents are traditionally prescribed puberty blockers to limit them from going through puberty as their natal sex, as this can make it more difficult to physically transition to the other sex. It can additionally be traumatic for those who undergo puberty while strongly gender dysphoric.

There is some evidence that puberty blockers influence bones in negative ways. One study found that puberty blockers (GnRHa) led to statistically significant decreases in bone turnover during the time period in which they were applied. Another study indicates that bone mineral density is decreased significantly in both transwomen and transmen between the start of GnRHa application and age 22. The study concluded that “either attainment of peak bone mass has been delayed or peak bone mass itself is attenuated“. Clemons et al. (1993) additionally examined the effects of puberty blockers in non-trans instances and concludes they are safe and effective, after which puberty resumes normally. Yet they also point out potential problems regarding bone mineralization. Hruz et al., in a socially conservative publication, also posit risks of increased testicular cancer, obesity, memory loss, height decreases, and androgynous appearances. Overall there do appear to be risks to puberty blockers, and it is up to families to make the best decisions for themselves based on the potential consequences of adopting and not adopting blockers.

Additionally, if puberty is blocked, it cannot be used as a “diagnostic tool”, as Green refers to it. According to some researchers, (Steensma et al. 2011, Zucker 2018, narrative accounts of desistance) puberty is the stage at which many formerly dysphoric youth desist and begin expressing a gender identity in line with their biological sex. Yet others would push back against the use of puberty as a diagnostic tool due to the trauma it can cause to transgender individuals forced to go through puberty as their natal sex.

Narratives of puberty describe traumatic experiences for youth who experience gender dysphoria. If one feels their biological sex is wrong and they should have the opposite physical sex characteristics, those characteristics becoming more prominent can be extremely difficult. Coupled with the additional social pressures during puberty to conform to the gender that matches one’s biological sex, puberty can be difficult and scary for transgender individuals.

For instance, a mother reported her son named Patrick was, “Increasingly unhappy, suffering panic attacks and verging on depression, he told her if he could not go on puberty blockers he would run away and get them himself, or kill himself.” Another mom recalls that her child, Jackie, was “incredibly depressed” when she started puberty. The daughter was happy in elementary school, after social transitioning at 8, but “everything fell to pieces” when she started puberty, making six suicide attempts between the ages of eleven and fifteen. She overdosed and self-harmed with razor blades to distract from her changing body before being prescribed puberty blockers.

Steensma et al.’s (2011) qualitative study reports that, upon reaching puberty, “these anticipated or actual physical changes were often agonizing and highly distressful,” while, “at the beginning of puberty, the aversion towards their bodies intensified immensely, resulting in insecurity and social withdrawal”.

These psychological consequences of commencing puberty as a gender dysphoric child or youth must be weighed against any potential health effects when deciding about puberty blockers. A 2010 study of those placed on puberty blockers also indicates positive mental health effects of puberty blockers. From a T0 at the beginning of puberty blockers to a T1 around three years later, depressive symptoms significantly decreased, while scores on the internalizing problems also significantly decreased (from 29.6% to 11.1%). Trans boys did show still elevated levels of internalizing and externalizing problems but decreases from their previous rates. Overall, “Adolescents showed fewer behavioral and emotional problems, reported fewer depressive symptoms, feelings of anxiety and anger remained stable, and their general functioning improved.”

One other aspect of this study is that out of a sample of 70 individuals, none desisted, and all continued to receive treatment for gender dysphoria. This could possibly indicate that puberty blockers decrease the chance that an individual’s gender dysphoric feelings will go away, though it could also indicate that only those with strong feelings take puberty blockers in the first place.

Overall, puberty blockers appear to have some positive mental health effects due to their prevention of the physical experience of puberty among transgender youth, but may have physical health consequences including on bone growth.

Conclusion

On Desistence – The body of research on gender dysphoric youth indicates that many of these youths are no longer gender dysphoric upon reaching and progressing through puberty. It is possible that the youths that “desisted” either were not transgender in the first place or were pressured to disassociate from their transgender identity. Yet there are enough anecdotal accounts and extended studies regarding desisting youth to provide reasonable evidence that at least some, and likely a sizable fraction of individuals who express desires to be the gender opposite their natal sex or affirm that they are the opposite gender in childhood do not feel the same way at a later point in life.

On Determining Desistence – There is a lack of agreement between sources on whether gender dysphoric youth who will persist and desist can be differentiated from each other. On the whole, the evidence indicates there is a correlation between the strength of transgender expression (identifying as the other gender rather than simply expressing cross-gender behavior) and persistence, yet the correlation isn’t perfect. Some children who express a strong desire that they are the other gender desist, while some children with subthreshold gender dysphoria diagnoses persist through puberty.

On Social Transitioning – Social transitioning has positive mental health effects, but unknown effects on whether children will persist or desist. Social transitioning is put forward as one of the primary ways to support transgender children and is shown to reduce the rates of internalizing problems and anxiety among gender dysphoric youth. These children do still show elevated rates of anxiety. Additionally, some children who socially transition later do not feel gender dysphoric anymore and decide to not present as the opposite gender any longer. There is no evidence examining the rate at which individuals who socially transition retain their gender dysphoric feelings and transgender identities.

On Puberty Blockers – Puberty blockers, though reportedly safe, may have unintended medical consequences based on a review of studies. Studies show effects on bone growth and density. Yet other studies show positive mental health effects relative to transgender individuals who undergo puberty as their birth sex, as puberty is a time when living as a transgender individual can be particularly traumatic. It is unknown if placing individuals on puberty blockers affects the rate at which that population of individuals retains their gender dysphoria.

Notes

-

This does not indicate a preference for desistence of gender dysphoric youth, but merely indicates that these types of long-term effects are something policy makers, medical experts, and trans advocates may wish to consider. ↩

-

Dutch study. The numbers don’t include nonresponders. ↩

-

Ph.D. thesis, University of Toronto. ↩

-

Dutch study. The numbers don’t include nonresponders. ↩

-

1 “Transsexual” and 1 “Homosexual, cross dresses”

-

Canadian study, University of Toronto. ↩