Age Gaps And Birth Order Effects

[Parts of this post have since been shown to be wrong, as explained in this post. I endorse this reanalysis as better than the current post.]

Psychologists are split on the existence of “birth order effects”, where oldest siblings will have different personality traits and outcomes than middle or youngest siblings. Although some studies detect effects, they tend to be weak and inconsistent.

Last year, I posted Birth Order Effects Exist And Are Very Strong, finding a robust 70-30 imbalance in favor of older siblings among SSC readers. I speculated that taking a pre-selected population and counting the firstborn-to-laterborn ratio was better at revealing these effects than taking an unselected population and trying to measure their personality traits. Since then, other independent researchers have confirmed similar effects in historical mathematicians and Nobel-winning physicists. Although birth order effects do not seem to consistently affect IQ, some studies suggest that they do affect something like “intellectual curiosity”, which would explain firstborns’ over-representation in intellectual communities.

Why would firstborns be more intellectually curious? If we knew that, could we do something different to make laterborns more intellectually curious? A growing body of research highlights the importance of genetics on children’s personalities and outcomes, and casts doubt on the ability of parents and teachers to significantly affect their trajectories. But here’s a non-genetic factor that’s a really big deal on one of the personality traits closest to our hearts. How does it work?

People looking into birth order effects have come up with a couple of possible explanations:

1. Intra-family competition. The oldest child choose some interest or life path. Then younger children don’t want to live in their older sibling’s shadow all the time, so they do something else.

2. Decreased parental investment. Parents can devote 100% of their child-rearing time to the oldest child, but only 50% or less to subsequent children.

3. Changed parenting strategies. Parents may take extra care with their firstborn, since they are new to parenting and don’t know what small oversights they can get away with vs. what will end in disaster. Afterwards, they are more relaxed and willing to let the child “take care of themselves”. Or they become less interested in parenting because it is no longer novel.

4. Maternal antibodies. Studies show that younger sons with older biological brothers (but not sisters!) are more likely to be homosexual. This holds true even if someone is adopted and never met their older brother. The most commonly-cited theory is that during a first pregnancy, the mother’s immune system may develop antibodies to some unexpected part of the male fetus (maybe androgen receptors?) and damages these receptors during subsequent pregnancies. A similar process could be responsible for other birth order effects.

5. Maternal vitamin deficiencies. An alert reader sent me Does Birth Spacing Affect Maternal Or Child Nutritional Status? It points out that people maintain “stockpiles” of various nutrients in their bodies. During pregnancy, a woman may deplete her nutrient stockpiles in the difficult task of creating a baby, and the stockpiles may take years to recover. If the woman gets pregnant again before she recovers, she might not have enough nutrients for the fetus, and that may affect its development.

How can we distinguish among these possibilities? One starting point might be to see how age gaps affect birth order effects. How close together do two siblings have to be for the older to affect the younger? If a couple has a child, waits ten years, and then has a second child, does the second child still show the classic laterborn pattern? If so, we might be more concerned about maternal antibodies or changes in parenting style. If not, we might be more concerned about vitamin deficiencies or distracted parental attention.

Methods And Results

I used the 2019 Slate Star Codex survey, in which 8,171 readers of this blog answered a few hundred questions about their lives and opinions.

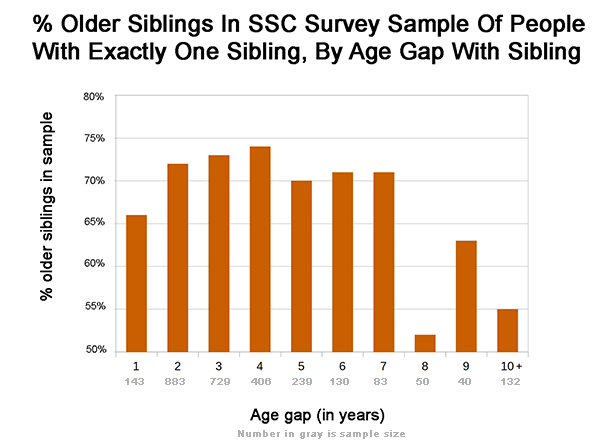

Of those respondents, I took the subset who had exactly one sibling, who reported an age gap of one year or more, and who reported their age gap with an integer result (I rounded non-integers to integers if they were not .5, and threw out .5 answers). 2,835 respondents met these criteria.

Of these 2,835, 71% were the older sibling and 29% were the younger sibling. This replicates the results from last year’s survey, which also found that 71% of one-sibling readers were older.

Here are the results by age gap:

Birth order effects are strong from one-year to seven-year age gaps, and don’t differ much within that space. After seven years, birth order effects decrease dramatically and are no longer significantly different from zero.

Birth order effects are strong from one-year to seven-year age gaps, and don’t differ much within that space. After seven years, birth order effects decrease dramatically and are no longer significantly different from zero.

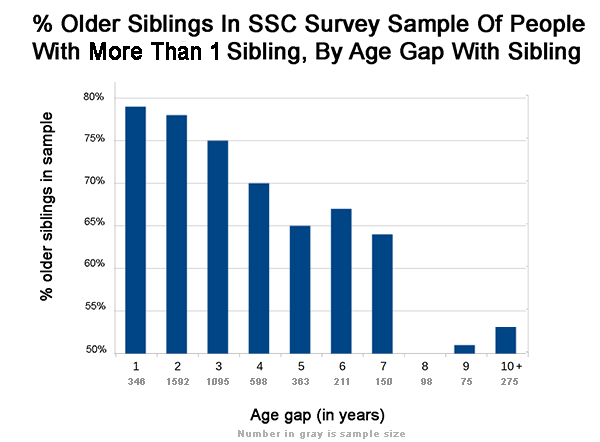

I also investigated people who had more than one sibling, but were either the oldest or the youngest in their families.

More siblings =

More siblings = more problems more of a birth order effect, but the overall pattern was similar. There is a possible small decline in strength from one to seven years, followed by a very large decline between seven and eight years.

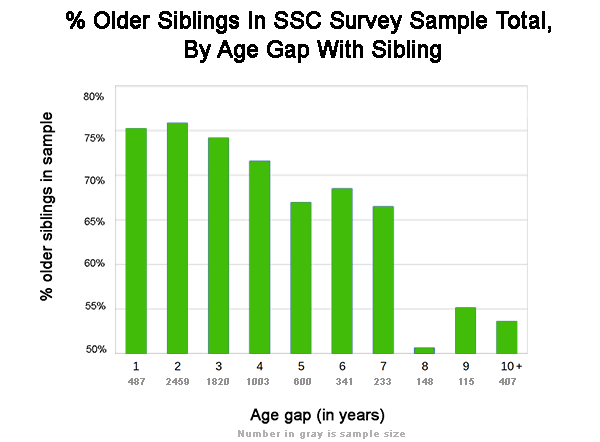

Here’s the previous two graphs considered as a single very-large-n sample:

The pattern remains pretty clear: vague hints of a decline from age 1 to 7, followed by a very large decline afterwards.

The pattern remains pretty clear: vague hints of a decline from age 1 to 7, followed by a very large decline afterwards.

(Tumblr user athenaegalea kindly double-checked my calculations; you can see her slightly-differently-presented results here).

Weirdly, among people who reported a zero-year age gap, 70% are older siblings. This wouldn’t make much sense for twins, since here older vs. younger just means who made it out of the uterus first. I don’t know if this means there’s some kind of reporting error that discredits this entire project, whether people who were born about 9 months apart reported this as a zero year age gap, or whether it’s just an unfortunate coincidence.

These results suggest that age gaps do affect the strength of birth order effects. People with siblings seven or fewer years older than them will behave as laterborns; people separated from their older siblings by more than seven years will act like firstborn children.

Discussion

This study found an ambiguous and gradual decline from one to seven years, but also a much bigger cliff from seven to eight years. Is this a coincidence, or is there something important that happens at seven?

Most of the sample was American; in the US, children start school at about age five. Although it might make sense for older siblings stop mattering once they are in school, this would predict a cliff at five years rather than seven years.

Developmental psychologists sometimes distinguish between early childhood (before 6-8 years) and middle childhood (after that point). This is supposed to be a real qualitative transition, just like eg puberty. We might take this very seriously, and posit that having a sibling in early childhood causes birth order effects, but one in middle childhood doesn’t. But why should this be? Overall I’m still pretty confused about this.

These results may be consistent with an intra-family competition hypothesis. Children try to avoid living in the shadow of their older siblings, perhaps by avoiding intellectual pursuits those children find interesting. But if there is too much of an age gap, then siblings are at such different places that competition no longer feels relevant.

These results may be partly consistent with a parental investment hypothesis. Parents might have to split their attention between first and laterborn children, so that laterborns never get the period of sustained parental attention that firstborns do. But since an age gap as small as one year produces this effect, this would suggest that only the first year of childrearing matters; after the first year, even the firstborn children in this group are getting split attention. This is hard to explain if we are talking about as complicated a trait as “intellectual curiosity” – surely there are things parents do when a child is two or three to make them more curious?

These results don’t seem consistent with hypotheses based on changing parenting strategies or maternal antibodies, unless parenting strategies or the immune system “reset” to their naive values after a certain number of years.

They also don’t seem too consistent with vitamin-based hypotheses. I don’t know how long it takes to replenish vitamin stockpiles, and it’s probably different for every vitamin. But I would be surprised if giving people one vs. five years for this had basically no effect, but giving them eight instead of seven years had a very large effect. Overall I would expect the first year of vitamin replenishment to be the most important, with diminishing returns thereafter, which doesn’t fit the birth order effect pattern.

Overall these results make me lean slightly more towards intra-family competition or parental investment as the major cause of birth order effects. I can’t immediately think of a way to distinguish between these two hypotheses, but I’m interested in hearing people’s ideas.

I welcome people trying to replicate or expand on these results. All of the data used in this post are freely available and can be downloaded here.