Does the Glasgow Coma Scale exist? Do comas?

[Epistemic status: I am quite confident I am not making a *small* mistake here. Either I am right, or I have completely misunderstood the entire premise of the debate.]

I.

One of the more interesting responses I got to yesterday’s discussion of IQ:

Let me ask you this, though, what would lead you to believe “g” is not a real thing? What would lead you to be more in favor of “g” being a real thing (e.g. out there in the real causal model of the world). For example, I don’t think this is really evidence for “g” as a real thing.

I can invent an abstraction called “hit points” that is a function of your vital life signs you measure in a modern hospital. Then I point out that it varies in a dose dependent way with being hit with a hammer. In what sense is this evidence that hit points are real?

“Hit points” is me applying the modeling philosophy behind “g” to healthcare (something Scott knows quite a bit about). It is safe to replace “hp” by “g” in any sentence.

Many fields of medicine depend heavily upon abstractions of exactly this sort. If I were being really mean, I’d make you learn about APACHE III, but for the sake of simplicity let’s look at the Glasgow Coma Scale instead.

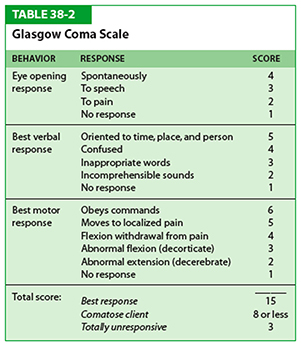

Every medical student knows about the Glasgow Coma Scale and it is used in every hospital in the country. It is exactly what you probably think it is – a scale measuring the degree to which someone is in a coma. You can think of it as a hit point system covering those last few hit points – the ones between -1 and -9, where you’re dying but not quite dead.

Instead of going from -1 to -9, the GCS goes from 15 to 3. It adds together three subscales, Eyes, Verbal, and Motor. Eyes for example offers 4 points to people with their eyes open, 3 points to people with closed eyes who open them when you talk to them, 2 points to people who open their eyes in response to painful stimuli, and 1 point to people who never open their eyes at all.

Add it all up and you get a pretty good idea how deep a coma someone is in.

Add it all up and you get a pretty good idea how deep a coma someone is in.

This is useful for a lot of reasons. If you give a comatose person a medication, you might want to check whether they’re getting worse or better by watching if their Glasgow Coma score goes up or down. Or you might want to know when to perform certain drastic interventions (like intubating a patient or transferring them to ICU) and you can study outcomes for different interventions in patients with different Glasgow Coma scores. A patient with a score of 14 is still pretty okay and intubating them would usually be silly; a patient with a score of 4 is very ill and probably needs intubation right away. Various people did lots of studies to discover which Glasgow Coma scores do and don’t need intubation, eventually leading to the ancient Medical proverb: “Score of eight, intubate”

(also: “Score of nine, nah he’s fine”. Given that I work in a Catholic hospital, you can guess what we rhyme “seven” with)

Although it is not an official use, a lot of people use GCS as a quick and dirty way of estimating someone’s chances. In a particular ICU, it was discovered that mortality rates ranged from about 10% at GCS 11 to about 66% at GCS 3. Other indicators like the aforementioned APACHE are better for this, but GCS will do in a pinch.

II.

So that’s what Glasgow Coma Scale is. What would it mean to say “comas do not exist” or “the Glasgow Coma Scale does not exist”?

It’s important to distinguish between a couple of different interpretations of the question.

First, are comas a real thing? I would say that there is a common-sense concept of being-in-a-coma which is valuable in predicting various things we want to predict, like whether someone is able to talk and able to walk and able to solve math problems and so on. I would say that different people differ in the degree to which they are in comas. I feel very strongly about this.

Second, is the GCS an okay proxy for our common-sense concept of being-in-a-coma? I’m not asking for some perfect Platonic identity here. I’m just saying that, for example, counting the number of letters in a person’s name, then multiplying by their birth date is a terrible proxy for whether or not that person is in a coma. Glasgow Coma Scale seems to probably be very well correlated with asking for people’s subjective opinions about whether someone is in a coma or not and if so how deep the coma is. It conveys well beyond zero information about this. I feel pretty strongly about this one too.

Third, does the GCS correctly predict the things we want it to predict? That is, does an increasing Glasgow Coma score really mean the patient is improving (as measured in things like not dying)? Does a lower Glasgow Coma score really mean the patient is more likely to need intubation? Are we sure that people don’t have exactly the same outcomes at every Glasgow Coma Score, or that it doesn’t go up and down like a roller coaster and someone with a score of 10 does better than 9 but worse than 8? As far as I know, all the research suggests that it predicts outcomes just fine.

Fourth, is the Glasgow Coma Scale measuring a single General Factor Of Comatoseness which is the sole cause of comas in the entire world? I don’t think anybody thinks that it does or expects it to.

It’s possible I don’t understand what it would mean for there to be a General Factor Of Comatoseness, so let me try to sketch two scenarios, one of which I would interpret as having such a GFOC and one of which I wouldn’t.

Scenario One: suppose that it were discovered that comas are not, in fact, caused by organ failure. Cells in failing organs secrete a chemical that activates an immune response – let’s call this comaleukin. When comaleukin gets too high, the cells that produce normal conscious behavior shut down and the patient falls into a coma. It is proven that in people genetically unable to produce comaleukin, no coma ever occurs – the patient is completely conscious until they suddenly drop dead. On the other hand, injecting comaleukin into a healthy patient causes them to fall into a coma. The more you inject, the deeper the coma is. It is discovered that there is a perfect linear relationship between amount of comaleukin in the blood and score on the Glasgow Coma Scale. In this case, comaleukin is a General Factor Of Comatoseness.

Scenario Two: you need working heart, brain, and liver to survive. If each of these three organs are working at 100% efficiency, you have a total of 300 Health Points. If you ever drop below 150 Health Points, you go into a coma. It is discovered that score on the Glasgow Coma Scale is exactly equivalent to (Number Of Health Points/10). In this case there is no General Factor Of Comatoseness; instead, there are three different factors representing the health of the heart, brain, and liver.

III.

If this is what is meant by a General Factor, I conclude I really couldn’t care less if I have one. Like, it seems very clear to me that comas exist, and are important, and are accurately measured by the Glasgow Coma Scale – whether or not there is any such Factor.

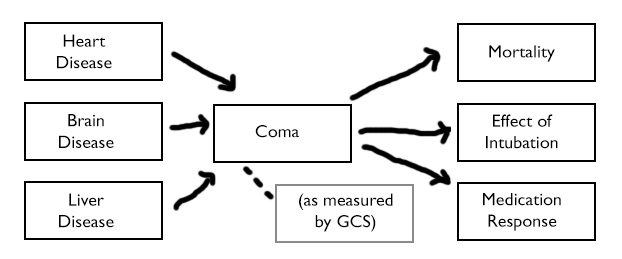

Like, here’s how I imagine the causal graph. If I change it so that “Heart Disease”, “Brain Disease” etc all point to a node marked “Comaleukin Levels”, and then that node points to “Coma”, so what?

Like, here’s how I imagine the causal graph. If I change it so that “Heart Disease”, “Brain Disease” etc all point to a node marked “Comaleukin Levels”, and then that node points to “Coma”, so what?

If some experiment had previously established that people with Heart Disease had a 40% chance of ending up with a GCS less than 5, learning about comaleukin doesn’t change that result at all. If another experiment showed that right-handed people went into deeper comas than left-handed people, it doesn’t change that result either.

And if some experiment had previously established that people with GCS 10 had a 15% mortality rate, learning about comaleukin doesn’t change that either. If another experiment showed that it was extremely important to intubate people below GCS 8, well, that also doesn’t change.

What seems to be happening is that all of the causative factors – heart disease, brain disease, liver disease – are going into a giant pot called “COMA”. Then we are drawing predictions out of that giant pot.

Learning about the existence (or non-existence) of comaleukin helps describe the internal structure of that pot and gives us more predictive power, but it doesn’t tell us that the predictions we made using the giant pot were wrong. It just (potentially) gives us an option to improve those predictions.

Learning about the existence (or non-existence) of comaleukin helps describe the internal structure of that pot and gives us more predictive power, but it doesn’t tell us that the predictions we made using the giant pot were wrong. It just (potentially) gives us an option to improve those predictions.

For example, suppose comas caused by heart disease have much higher mortality rates than comas caused by any other kind of disease. In that case, instead of drawing predictions from the giant pot, we might want to make a more sophisticated prediction algorithm that took heart disease, liver disease, and brain disease as separate variables and weighted the heart disease variable more strongly when trying to determine mortality.

Or maybe the contribution of liver disease to a coma is independent of its contribution to any interesting outcome like death. Then we might want to remove liver disease from the pot.

But if we decided not to do this, and we’d previously found the giant pot to be 90% accurate in making our mortality calculations, well, the giant pot would remain 90% accurate at doing that.

In contrast, if we learned that all comas were caused by comaleukin and nothing else, we would know for sure that we would never be able to beat the giant pot. But that discovery would not in itself make the giant pot more valuable to us.

IV.

Compare the Glasgow Coma Scale to blood pressure.

Almost everyone would say blood pressure is “real”. For goodness sakes, it’s measured directly! Using machines! Called sphygmomanometers, which are clearly very important given the number of complicated Greek-sounding letter combinations in their name!

On the other hand, causally it’s not obvious to me that blood pressure works any different from the Glasgow Coma Scale.

We do not measure blood pressure directly. We have a good proxy for blood pressure in the form of certain sounds made by blood when cuffs are contracted to certain levels. This is only moderately accurate – everyone in health care knows that the doctor is always going to get a different blood pressure reading than the nurse and neither of them is going to get anywhere near what the automated machine detects. I will bet money that two doctors using the Glasgow Coma Scale will have better inter-rater agreement than two doctors using a blood pressure cuff.

Blood pressure, like comas, is caused by multiple different factors. The two most important are heart rate and vascular caliber. A blood pressure reading of 50/30 could mean your heart isn’t beating much. Or it could just mean your vessels are super dilated for some reason. Or it could mean a lot of other things.

Blood pressure, like comas, are used to predict outcomes of interest. There are calculators that will tell you your likelihood of getting a heart attack or a stroke at certain blood pressure levels.

And blood pressure, like comas, is kind of fuzzy. Your blood pressure in your legs and lower body may be completely different from your blood pressure in your arms (medical students reading this blog to procrastinate studying for your USMLEs: what condition does this classically imply?) In fact, your blood pressure in your right arm may be completely different from your blood pressure in your left arm. Your blood pressure may vary wildly over the course of the day, and it may vary between sitting and standing.

And, as commenters in the last post pointed out, pressure is an abstraction over millions of different blood cells doing their own thing – a multifactorial process if there ever was one.

When your doctor tells you “Your blood pressure is 146, eat less salt”, it’s hard to tell what exactly makes this number more “real” than your doctor telling you that you have a coma score of 12 – except that sphygmomanometers look a lot more impressive than a medical student sitting around with a questionnaire trying to see how hard she has to poke you before you can open your eyes.

I feel like Glasgow Coma Score and blood pressure on on pretty much the same ontological ground. Various factors go into them. Then you use them to predict various other factors. Whether they are “real” or “abstractions” seems to me to be beyond the scope of medicine and more into the realm of mysticism.

“By doing certain things certain results will follow; students are most earnestly warned against attributing objective reality or philosophic validity to any of them.”

V.

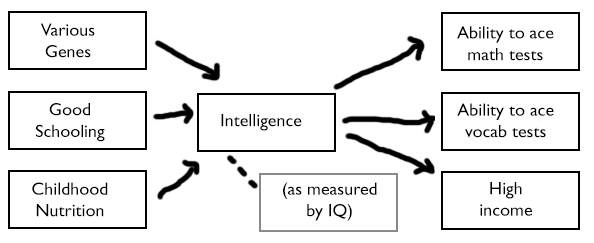

IQ seems to me to work much the same way.

I realize the most controversial part of this graph should be the word “INTELLIGENCE” in the center. But if you’re complaining about that, did you complain about “COMA” before? Comas are made of various subfactors, like inability-to-speak, inability-to-move, et cetera. These subfactors are mostly correlated, so it’s fair to lump them together into a single factor-category called “COMA” if we want. Likewise, whatever multiple intelligences there may be are correlated and so lumping them into a single factor-category called “INTELLIGENCE” seems both fun and profitable. If you didn’t object to the one, I hope you feel at least a little bad objecting to the other.

I realize the most controversial part of this graph should be the word “INTELLIGENCE” in the center. But if you’re complaining about that, did you complain about “COMA” before? Comas are made of various subfactors, like inability-to-speak, inability-to-move, et cetera. These subfactors are mostly correlated, so it’s fair to lump them together into a single factor-category called “COMA” if we want. Likewise, whatever multiple intelligences there may be are correlated and so lumping them into a single factor-category called “INTELLIGENCE” seems both fun and profitable. If you didn’t object to the one, I hope you feel at least a little bad objecting to the other.

I think most researchers agree there are lots of different factors affecting intelligence. Even if we limit ourselves to genes, most geneticists agree there are thousands of different ones that can make you a little smarter or a little dumber. Into the big pot they all go.

Heart disease, brain disease, and liver disease all have a common result: you lie motionless in a hospital bed with your eyes closed and don’t talk much. The degree to which this common end result has been realized gets measured by the Glasgow Coma Scale and used to predict mortality, intubation response, et cetera.

Bad genes, bad nutrition, and bad schooling all have a common result: you’re not very good at various correlated cognitive tasks. The degree to which this common end result has been realized gets measured by IQ tests and used to predict income, likelihood of criminal offending, and how well you do on other correlated cognitive tasks that you haven’t been tested on.

Just as it would be neat to discover that comas were caused by the chemical comaleukin, an easily detected physical intermediary corresponding to the observed common result of “being in a coma” – so it would be neat to discover that intelligence was caused by (let’s say) number of neurons in the brain, an easily detected physical intermediary corresponding to the observed common result of “being good at solving these sorts of cognitive tasks”.

The important part is that a lot of different causes all get mixed together into one pot, the contents of the pot can be observed with a test, and then the results of that test can be used to make important predictions.

VI.

I worry that people who say “Intelligence doesn’t exist” or “IQ isn’t a real science” are using a motte and bailey.

Consider the actual controversial claims about intelligence that people would like to refute. For example, “Intelligence is at least 50% heritable” or “Ashkenazi Jews have higher intelligence than Gentiles”.

Neither of these things really has any relationship to whether there’s a General Factor Of Intelligence or a thousand different factors.

(one might ask: if there are a thousand different factors, isn’t it unlikely that Ashkenazi Jews are better at all of them, or enough of them to make a difference? Not necessarily. For example, in our heart-brain-liver model there are three factors of comatoseness, but someone who just drank five bottles of vodka all at once will have worse brain function, heart function, and liver function than someone who didn’t. Likewise, even if there are a thousand genes that affect intelligence, someone with high mutational load may have less functional versions of all one thousand of them)

All you need to do to show that intelligence is at least 50% heritable is do some twin studies using some measurement of intelligence which everybody agrees corresponds to our intuitive use of the term.

All you need to do to show that Ashkenazi Jews are more intelligent than Gentiles is get some Jews and some Gentiles to take IQ tests and see what the average result is.

(this may be slightly more clear if we replace the loaded term “intelligence” with the mostly-synonymous term “problem-solving ability”. If we want to know if Ashkenazi Jews have higher problem-solving ability, the obvious experiment is to ask them to solve some problems!)

The bailey for “intelligence doesn’t exist” is that statements like ‘intelligence is heritable’ or ‘Ashkenazi Jews have higher intelligence’ can’t possibly have meaning and so we don’t have to think about them.

The motte is “We don’t know if there’s a single general factor that shapes intelligence.”

But the motte is so broad that it can apply to comas or to virtually anything else, things that nobody seriously questions the existence of.

Intelligence exists enough that all statements about intelligence except those being made in a very specific neuroscience-y sort of context can still be true and interesting.