No Clarity Around Growth Mindset

I.

Admitting a bias is the first step to overcoming it, so I’ll admit it: I have a huge bias against growth mindset.

(if you’re not familiar with it, growth mindset is the belief that people who believe ability doesn’t matter and only effort determines success are more resilient, skillful, hard-working, perseverant in the face of failure, and better-in-a-bunch-of-other-ways than people who emphasize the importance of ability. Therefore, we can make everyone better off by telling them ability doesn’t matter and only hard work does. More on Wikipedia here).

It’s unnatural, is what it is. A popular psychological finding that doesn’t have gruff people dismissing it as a fad? That doesn’t have politicians condemning it as a feel-good justification for everything wrong with society? That doesn’t have a host of smarmy researchers saying that what, you still believe that, didn’t you know it failed to replicate and has since been entirely superseded by a new study out of Belarus? I’m not saying Carol Dweck has definitely made a pact with the Devil, I’m just saying I don’t have a good alternative explanation.

Which brings me to the second reason I’m biased against it. Good research shows that inborn ability (including but not limited to IQ) matters a lot, and that the popular prejudice that people who fail just weren’t trying hard enough is both wrong and harmful. Social psychology has been, um, very enthusiastic about denying that result. If all growth mindset did was continue to deny it, then it would be unexceptional. But growth mindset goes further. It’s not (just?) that ability doesn’t matter. It’s that belief that ability might matter is precisely what makes people fail. People who believe ability matters will refuse to work hard, will avoid challenges, will become “helpless” in the face of pressure, will hate learning as a matter of principle, will refuse to work hard, will become blustery and defensive about their “brilliance”, will lie to people and hide their failures, and will drop out of school and turn to drugs (really)! People who believe that anyone can succeed if they try hard enough will be successful, well-adjusted, and treat life as a series of challenging adventures. It all strikes a curmudgeon like me as just about the thickest morality tale since Pilgrim’s Progress, and as just about the most convenient explanatory coup since “the reason psychic powers don’t work on you is because you’re a skeptic!”

Which brings me to the third reason I’m biased against it. It is right smack in the middle of a bunch of fields that have all started seeming a little dubious recently. Most of the growth mindset experiments have used priming to get people in an effort-focused or an ability-focused state of mind, but recent priming experiments have famously failed to replicate and cast doubt on the entire field. And growth mindset has an obvious relationship to stereotype threat, which has also started seeming very shaky recently.

So I have every reason to be both suspicious of and negatively disposed toward growth mindset. Which makes it appalling that the studies are so damn good.

Consider Dweck and Mueller 1998, one of the key studies in the area. 128 fifth-graders were asked to do various puzzles. First they did some easy ones and universally succeeded. The researchers praised them as follows:

All children were told that they had performed well on this problem set: “Wow, you did very well on these problems. You got [number of problems] right. That’s a really high score!” No matter what their actual score, all children were told that they had solved at least 80% of the problems that they answered.

Some children were praised for their ability after the initial positive feedback: “You must be smart at these problems.” Some children were praised for their effort after the initial positive feedback: “You must have worked hard at these problems.” The remaining children were in the control condition and received no additional feedback.

This is a nothing intervention, the tiniest ghost of an intervention. The experiment had previously involved all sorts of complicated directions and tasks, I get the impression they were in the lab for at least a half hour, and the experimental intervention is changing three short words in the middle of a sentence.

And what happened? The children in the intelligence praise condition were much more likely to say at the end of the experiment that they thought intelligence was more important than effort (p < 0.001) than the children in the effort condition. When given the choice, 67% of the effort-condition children chose to set challenging learning-oriented goals, compared to only 8% (!) of the intelligence-condition. After a further trial in which the children were rigged to fail, children in the effort condition were much more likely to attribute their failure to not trying hard enough, and those in the intelligence condition to not being smart enough (p < 0.001). Children in the intelligence condition were much less likely to persevere on a difficult task than children in the effort condition (3.2 vs. 4.5 minutes, p < 0.001), enjoyed the activity less (p < 0.001) and did worse on future non-impossible problem sets (p…you get the picture). This was repeated in a bunch of subsequent studies by the same team among white students, black students, Hispanic students…you probably still get the picture.

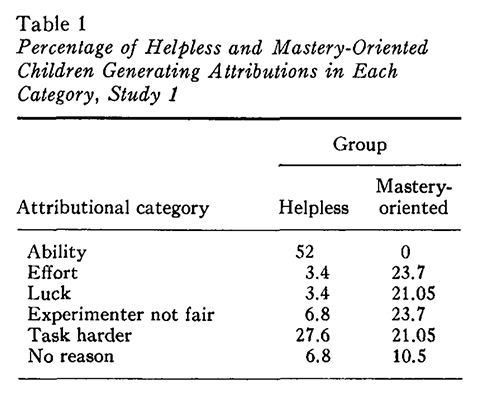

Or take An Analysis Of Learned Helplessness. Dweck has used a test called the IAR to separate children out into those who think effort is more important (“mastery-oriented”) and those who think ability is more important (“helpless”). Then she gave all of them impossible problems and watched them squirm – or, more formally, tested how long the two groups continued working on them effectively. She found extremely strong results – of the 30 subjects in each group, 11 of the mastery-oriented tried harder after failure, compared to 0 helpless. 21 of the helpless children stopped trying hard after failure, compared to only 4 mastery-oriented. She described the mastery-oriented children as saying things like “I love a challenge,” and the helpless children begging to be allowed to stop.

This study is really weird. Everything is like 100% in one group versus 0% in another group. Either something is really wrong here, or this one little test that separates mastery-oriented from helpless children constantly produces the strongest effects in all of psychology and is never wrong. None of the children whose test responses indicated that they thought ability was important to success ever monitored their own progress – not one – while over 95% of the children who said they thought effort was more important did. None of them ever expressed a positive statement about their own progress, while over two-thirds of the children who thought effort was more important did.

Normally I would assume these results are falsified, but I have looked for all of the usual ways of falsifying results and I can’t find any. Also, the boldest falsifier in the world wouldn’t have the courage to put down numbers like these. And a meta-analysis of all growth mindset studies finds more modest, but still consistent, effects, and only a little bit of publication bias. So – is growth mindset the one concept in psychology which throws up gigantic effect sizes and always works? Or did Carol Dweck really, honest-to-goodness, make a pact with the Devil in which she offered her eternal soul in exchange for spectacular study results?

Normally I would assume these results are falsified, but I have looked for all of the usual ways of falsifying results and I can’t find any. Also, the boldest falsifier in the world wouldn’t have the courage to put down numbers like these. And a meta-analysis of all growth mindset studies finds more modest, but still consistent, effects, and only a little bit of publication bias. So – is growth mindset the one concept in psychology which throws up gigantic effect sizes and always works? Or did Carol Dweck really, honest-to-goodness, make a pact with the Devil in which she offered her eternal soul in exchange for spectacular study results?

I don’t know. But here are a few things that predispose me towards the latter explanation. A warning – I am way out of my league here and post this only hoping it will spark further discussion.

II.

The first thing that bothers me is the history.

I’ve been trying really hard to trace its origin story, but it is pretty convoluted. It seems to have grown out of a couple of studies Carol Dweck and a few collaborators did in the seventies. But these studies generally found that a belief in innate ability was a positive factor alongside belief in growth mindset, with the problem children being the ones who attributed their success or failure to bad luck, or to external factors like the tests being rigged (which, by the way, they always were).

A good example of this genre is Learned Helplessness And Reinforcement Responsibility In Children. Its abstract describes the finding as: “Subjects who showed the largest performance decrements were those who took less personal responsibility for the outcomes of their actions…and who, when they did accept responsibility, attributed success and failure to presence or absence of ability rather than to expenditure of effort.”

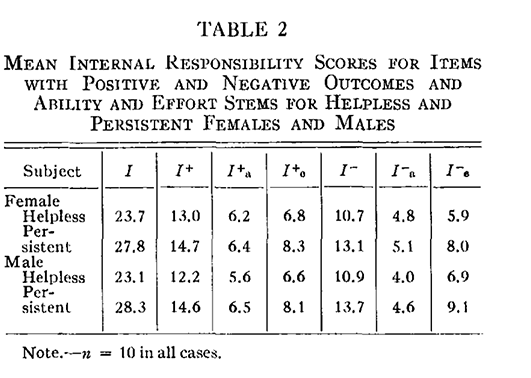

But that seems like a somewhat loaded way of interpreting this table:

As you can see, the “persistent” children (the ones who kept going in the face of failure) had stronger belief in the role of ability in their successes (I+a) and failures (I-a) than the “helpless” children (the ones who gave up in the face of failure)! These don’t achieve statistical significance in this n = 10 study, but they do repeat across all four combinations of success x gender tested. The real finding of the study was that children who attributed their success or failure to any stable factor, be it effort or ability, did better than those who did not. Likewise, in The Role Of Expectations And Attributions, Dweck describes her findings as “persistent and helpless children do not differ in the degree to which they attribute success to ability”. When you actually look at the paper, this is another case of the persistent children actually having a higher belief in the importance of ability, which fails to achieve statistical significance because the study is on a grand total of twelve children.

As you can see, the “persistent” children (the ones who kept going in the face of failure) had stronger belief in the role of ability in their successes (I+a) and failures (I-a) than the “helpless” children (the ones who gave up in the face of failure)! These don’t achieve statistical significance in this n = 10 study, but they do repeat across all four combinations of success x gender tested. The real finding of the study was that children who attributed their success or failure to any stable factor, be it effort or ability, did better than those who did not. Likewise, in The Role Of Expectations And Attributions, Dweck describes her findings as “persistent and helpless children do not differ in the degree to which they attribute success to ability”. When you actually look at the paper, this is another case of the persistent children actually having a higher belief in the importance of ability, which fails to achieve statistical significance because the study is on a grand total of twelve children.

(I should say something else about this study. Dweck compared two interventions to make children less helpless and better at dealing with failure. In the first, she gave them a lot of easy problems which they inevitably succeeded on and felt smart about. In the second, she gave them difficult problems they were bound to fail, then told them it was because they weren’t working hard enough. Finally, both groups were challenged with the difficult bound-to-fail problems to see how hard they tried on them. The children who had been given the impossible problems before did better than the ones who felt smart because they’d only gotten easy problems. Dweck interpreted this to prove that telling children to work hard made them less helpless. To me the obvious conclusion is that children who are used to failing get less flustered when presented with impossible material than children who have artificially been made to succeed every moment until now.)

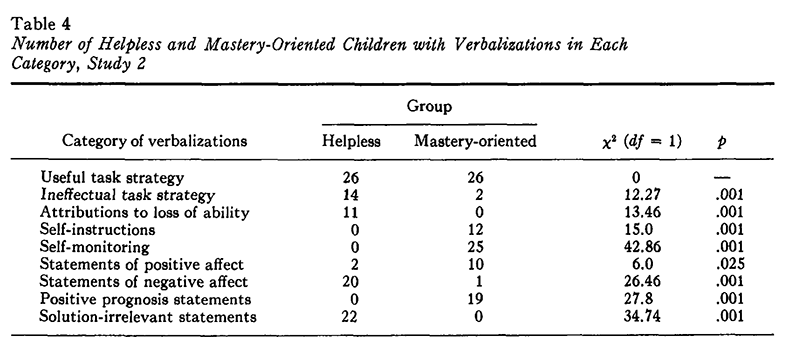

Then there’s there’s this, a preliminary to the second study I mentioned in Part I. Does it show the mastery-oriented children outperforming the helpless children on every measure. Yeah. But listen to this part from the discussion section:

The results revealed striking differences both in the pattern of performance and in the nature of the verbalizations made by helpless and mastery-oriented children following failure. It was particularly noteworthy that while the helpless children made the expected attributions to uncontrollable factors, the mastery-oriented children did not offer explanations for their failures

.

But if you look at the data, this doesn’t seem right.

Mastery-oriented children were about six times more likely to attribute their failures to the most uncontrollable factor of all – bad luck. They were also about six times more likely to attribute their failures to the task “not being fair”. This contradicts every previous study, including Dweck’s own. The whole field of attribution theory, which is intensely studied and which Dweck cites approvingly, says that attributing things to luck is a bad idea and attributing them to ability is, even if not as good as effort, pretty good. But Dweck finds that the kids who used ability attributions universally crashed and bomb, and the kids who attribute things to luck or the world being unfair do great. It might not be fair for me to pick on these couple of small studies in particular when there’s so much out there, but the fact is that these are the first, and a lot of the reviews cite only these and a few theses which as far as I know were never published. So this is what I’ve got. And from what I’ve got, I find that until about 1980, every study including Dweck’s found that belief in ability was a protective factor. Suddenly this disappeared and was replaced with it being a toxic plague. What happened? I don’t know.

Mastery-oriented children were about six times more likely to attribute their failures to the most uncontrollable factor of all – bad luck. They were also about six times more likely to attribute their failures to the task “not being fair”. This contradicts every previous study, including Dweck’s own. The whole field of attribution theory, which is intensely studied and which Dweck cites approvingly, says that attributing things to luck is a bad idea and attributing them to ability is, even if not as good as effort, pretty good. But Dweck finds that the kids who used ability attributions universally crashed and bomb, and the kids who attribute things to luck or the world being unfair do great. It might not be fair for me to pick on these couple of small studies in particular when there’s so much out there, but the fact is that these are the first, and a lot of the reviews cite only these and a few theses which as far as I know were never published. So this is what I’ve got. And from what I’ve got, I find that until about 1980, every study including Dweck’s found that belief in ability was a protective factor. Suddenly this disappeared and was replaced with it being a toxic plague. What happened? I don’t know.

III.

The second thing that bothers me is the longitudinal view.

So you have your helpless, fixed-mindset, believe-in-innate-ability children. According to Dweck, they “…are so concerned with being and looking talented that they never realize their full potential. In a fixed mindset, the cardinal rule is to look talented at all costs. The second rule is don’t work too hard or practice too much…having to work casts doubt on your ability. The third rule is, when faced with setbacks, run away. They say things like ‘I would try to cheat on the next test’. They make excuses, they blame others, they make themselves feel better by looking down on those who have done worse.”

These people sound like total losers, and it’s clear Dweck endorses this reading:

“Almost every great athlete – Michael Jordan, Jackie Joyner-Kersee, Tiger Woods…has had a growth mindset. Not one of these athletes rested on their talent…research has repeatedly shown that a growth mindset fosters a healthier attitude toward practice and learning, a hunger for feedback, a greater ability to deal setbacks, and significantly better performance over time…over time those with a growth mindset appear to gain the advantage and begin to outperform their peers with a fixed mindset.”

Man, it sure would be awkward if fixed mindset students generally did better than growth-mindset ones, wouldn’t it?

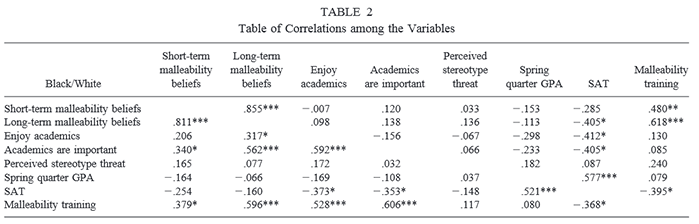

Aronson, Fried, and Good (2001) looks at first like just another stunning growth mindset study. They do a half-hour intervention to teach college students growth mindset and find they are still getting higher grades a couple of months later (an effect so shocking I wrote about it here). But one thing they do kind of as an afterthought is measure the students’ general level of growth mindset, as well as some measures of academic performance before the intervention.

People with high growth mindset had lower GPA (decent effect size but not statistically significant) and lower SAT scores (which was statistically significant). The authors are obviously uncomfortable with this, but they propose that people who get low SAT scores just tell themselves ability doesn’t matter/exist in order to protect their self-esteem since they don’t seem to have much of it.

People with high growth mindset had lower GPA (decent effect size but not statistically significant) and lower SAT scores (which was statistically significant). The authors are obviously uncomfortable with this, but they propose that people who get low SAT scores just tell themselves ability doesn’t matter/exist in order to protect their self-esteem since they don’t seem to have much of it.

And okay, that’s probably true (a commenter makes the equally good point that smart people may coast on their native intelligence without ever applying effort, and so accurately describe their experience as ability mattering but effort not doing so).

But if Dweck is to be believed, people with growth mindset are amazing ubermenschen and people with fixed mindset are disgusting failures at everything who hate learning and give up immediately and try to cheat. In the real world, however big the effect is, it is totally swamped by this proposed “people with low SAT scores protect their self-esteem or whatever” effect.

The same study also notes the awkward result that blacks are more likely to believe intelligence is flexible and growth-mindset-y than whites, even though blacks do worse in school and even though half the reason people are pushing growth mindset is to try to explain minority underperformance.

This is not an isolated finding. For example, Furnham (2003) finds in a sample of students at University College London that mindset is not related to academic performance. I’ve been told there’s a study from Pennsylvania that shows the same thing, though I can’t find it.

If you look hard enough, you can even notice this in Dweck’s studies themselves. One little-remarked-upon feature of Dweck’s work is that the helpless children and the mastery-oriented children always start out performing at the same level. It’s only after Dweck stresses them out with a failure that the mastery-oriented children recover gracefully and the helpless children go into free-fall.

But these are fifth-graders! For the two groups of children to do equally well on the first set of problems means that from first through fourth grade, their “helpless” “fixed-mindset” work-hating nature hasn’t impaired their ability to learn the material to a fifth-grade level one bit! (In this study, the fixed mindset children actually start out doing better; I can’t find any studies where the growth mindset children do).

When it’s convenient for her argument, Dweck herself admits that:

Some of the brightest, most skilled individuals exhibit the maladaptive pattern. Thus, it cannot be said that it is simply those with weak skills or histories of failure who (appropriately) avoid difficult tasks or whose skills prove fragile in the face of difficulty.

But I don’t think she follows the full implication of this statement, that despite being doomed to failure by their fixed mindset, these people have become “the brightest and most skilled individuals”.

Indeed, there has recently been some growth mindset studies done on gifted students, at elite colleges, or in high-level athletics. All of these dutifully show that people with fixed mindset respond much worse to whatever random contrived situation the experimenters produce. But thus far nobody has pointed out that there seem to be about as many of these people at, say, Stanford as there are anywhere else. If growth mindset was so great, you would expect fixed mindset people at Stanford to be as rare as, say, people with less than 100 IQ are at Stanford. Given that you will search in vain for the latter but have no trouble finding a bunch of the former for your study on how great growth mindset is, it sure looks like IQ is useful but growth mindset isn’t.

When people are in a psychology study, the fixed mindset individuals universally crash and bomb and display themselves to be totally incapable of learning or working hard. At every other moment, they seem to be doing equally well or better than their growth mindset peers. What’s going on? I have no idea.

IV.

The third thing that bothers me is Performance Deficits Following Failure, a study which manages to be quite interesting despite coming from a university in a city that very possibly doesn’t exist.

They use a procedure much like Dweck’s. They make children do some problems. Then they give them some impossible problems. Then they give them more problems, to see if they’ve developed “learned helplessness” from their failure on the impossible ones. Dweck’s theory predicts that the fixed-mindset children would and the growth mindset children wouldn’t. The Bielefeld team wasn’t testing growth mindset, but they indeed found that a bunch of children got flustered and stopped trying and did poorly from then on.

Then they repeated the experiment, but this time they made it look like no one would know how the children did. They told the kids they would be on teams, and the scores of everyone on their team would be combined before anybody saw it. The kids could fail as much as they wanted, and it would never reflect on them.

After that, children did exactly as well after failure as they had before. There was no sign of any decrease, or any “fixed mindset” group that suddenly gave up in order to protect their ego.

This doesn’t strike me as fully consistent with mindset theory. In mindset theory, people are acting based on their own deep-seated beliefs. Once a fixed mindset child fails, that’s it, she knows she’s Not Intelligent, there’s no helping it, all she can do is sabotage herself on the problems in order to protest a spiteful world that has failed to recognize her genius blah blah blah. Instead, there seems to be a very social role to these failures. The Bielefeld team describes it as “self-esteem protection”, but that doesn’t make much sense to me, since if they were worried about their self-esteem they could still be worried about it when no one else knew their performance.

To me it seems like some kind of interaction between self-esteem and other-esteem. Fixed mindset people get flustered when they have to fail publicly in front of scientists. This doesn’t seem like an unreasonable problem to have. A more interesting question is why it’s correlated with belief in innate ability.

Suppose that the difference in “people who talk up innate ability” and “people who talk up hard work” maps onto a bigger distinction. Some people really want to succeed at a task; other people just care about about clocking in, going through the motions, and saying “I did what I could”.

Put the first group in front of an authoritative-looking scientist, tell them to solve a problem, and make sure they can’t. They’re going to view this as a major humiliation – they were supposed to get a result, and couldn’t. They’ll get very anxious, and of course anxiety impedes performance.

Put the second group in front of an authoritative-looking scientist, and they’ll notice that if they write some stuff that looks vaguely relevant for a few minutes until the scientist calls time, then whatever, they can say they tried and no one can bother them about it. They do exactly this, then demand an ‘A’ for effort. At no point do they experience any anxiety, so their performance isn’t impeded.

Put both groups on their own in private, and neither feels any humiliation, and they both do about equally well.

Now put them in real life. The success-oriented group will investigate how to study most effectively; the busywork-oriented group will try to figure out how many hours of studying they have to put in before other people won’t blame them if they fail, then put in exactly that amount. You’ll find the success-oriented group doing a bit better in school, even though they fail miserably in Dweck-style experiments.

And if an experimenter praises children for working hard, it will make them believe that all the experimenter cares about is their effort. Next problem, when the experimenter poses an impossible question, the child will beat their head against it for no reason, since that’s apparently what the experimenter wants. But if the experimenter praises a child’s ability, then the child will feel like the experimenter really wants them to correctly solve the questions. When the next question proves unsolvable, the child will admit it and expect the experimenter to be disappointed.

I doubt that this is the real phenomenon behind growth mindset, simply because it flatters my own prejudices in much the same way mindset theory flatters everyone else’s. But I think it shows there are a lot of different narratives we could put in this space, all of which would be able to explain some of the experimental results.

V.

I want to end by correcting a very important mistake about growth mindset that Dweck mostly avoids but which her partisans constantly commit egregiously. Take this article, Why A Growth Mindset Is The Only Way To Learn:

[Some people think] you’ll always have a set IQ. You’re only qualified for the career you majored in. You’ll never be any better at playing soccer or dating or taking risks. Your life and character are as certain as a map. The problem is, this mindset will make you complacent, rob your self-esteem and bring meaningful education to a halt.

In short, it’s an intellectual disease and patently untrue.

The article goes on to show how growth mindset proves talent is “a myth”, a claim repeated by growth mindset cheerleader articles like Debunking The Genius Myth and The Learning Myth: Why I’ll Never Tell My Son He’s Smart and this woman who says we need to debunk the idea of innate talent.

Suppose everything I said in parts I – IV was wrong, and growth mindset is 100% true exactly as written.

This still would not provide an iota of evidence against the idea that innate talent / IQ / whatever is by far the most important factor determining success.

Consider. We know from countless studies that strong religious belief increases your life expectancy, makes you happier, reduces your risk of depression and reduces crime. Clearly believing in, say, Christianity has lots of useful benefits. But no one would dare argue that proves Christianity true. It doesn’t even imply it.

Likewise, mindset theory suggests that believing intelligence to be mostly malleable has lots of useful benefits. That doesn’t mean intelligence really is mostly malleable. Consider, if you will, my horrible graph:

Suppose this is one of Dweck’s experiments on three children. Each has a different level of innate talent, represented by point 1. After they get a growth mindset and have the right attitude and practice a lot, they make it to point 2. Two things are simultaneously true of this model. First, all of Dweck’s experiments will come out exactly as they did in the real world. Children who adopt a growth mindset and try hard and practice will do better than children who don’t. If many of them are aggregated into groups, the growth mindset group will on average do better than the ability-focused group. Intelligence is flexible, and if you don’t bother practicing than you fail to realize your full potential.

Suppose this is one of Dweck’s experiments on three children. Each has a different level of innate talent, represented by point 1. After they get a growth mindset and have the right attitude and practice a lot, they make it to point 2. Two things are simultaneously true of this model. First, all of Dweck’s experiments will come out exactly as they did in the real world. Children who adopt a growth mindset and try hard and practice will do better than children who don’t. If many of them are aggregated into groups, the growth mindset group will on average do better than the ability-focused group. Intelligence is flexible, and if you don’t bother practicing than you fail to realize your full potential.

Second, the vast majority of difference between individuals is due to different levels of innate talent. Alice, no matter how hard she practices, will never be as good as Bob. Bob, if he practices very hard, will become better than Carol was at the start, but never as good as Carol if she practices as hard as Bob does. The difference between Alice and Carol is a vast, unbridgeable gap which growth mindset has nothing whatsoever to say about.

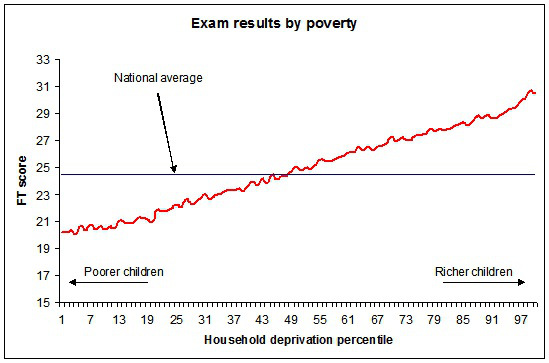

Here is a graph which is less terrible because it was not made by me. I have taken it from one of the two other sources I have found on the entire Internet that don’t like growth mindset:

We can argue all day about whether poor students do worse because they have bad health, because they have bad genes, because they have bad upbringings, or because society is fixed against them. We have argued about that all day before here, and it’s been pretty interesting. But in this case it doesn’t matter. If the only thing that affects success is how much effort you put in, poor kids seem to be putting in a heck of a lot less effort in a surprisingly linear way. But the smart money’s not on that theory.

We can argue all day about whether poor students do worse because they have bad health, because they have bad genes, because they have bad upbringings, or because society is fixed against them. We have argued about that all day before here, and it’s been pretty interesting. But in this case it doesn’t matter. If the only thing that affects success is how much effort you put in, poor kids seem to be putting in a heck of a lot less effort in a surprisingly linear way. But the smart money’s not on that theory.

A rare point of agreement between hard biodeterminists and hard socialists is that telling kids that they’re failing because they just don’t have the right work ethic is a crappy thing to do. It’s usually false and it will make them feel terrible. Behavioral genetics studies show pretty clearly that at least 50% of success at academics and sports is genetic; various sociologists have put a lot of work into proving that your position in a biased society covers a pretty big portion of the remainder. If somebody who was born with the dice stacked against them works very hard, then they might find themselves at A2 above. To deny this in favor of a “everything is about how hard you work” is to offend the sensibilities of sensible people on the left and right alike.

Go back to that 1975 paper above on “Role Of Expectations And Attributions” and look more closely at the proposed intervention to help these poor fixed mindset students:

Twelve extremely helpless children were identified [and tested on how many math problems they could solve in a certain amount of time]…the criterion number was set one above the number he was generally able to complete within the time limit. On these trials, he was stopped one or two problems short of criterion, his performance was compared to the criterion number required, and experimenter verbally attributed the failure to insufficient effort.

So basically, you take the most vulnerable people, set them tasks you know they’ll fail at, then lecture them about how they only failed because of insufficient effort.

Imagine a boot stamping on a human face forever, saying “YOUR PROBLEM IS THAT YOU’RE JUST NOT TRYING NOT TO BE STAMPED ON HARD ENOUGH”.

And maybe this is worth it, if it builds a growth mindset that allows the child to be more successful in school, sports, and in the rest of her life. But you’re not “debunking the myth of genius”. Genius remains super-important, just like conscientiousness and wealth and health and privilege and everything else. No, you’re telling a Noble Lie to the children because you think it’s useful. You can make it palatable by saying “Well, we’re not denying reality, we’re just selectively emphasizing certain parts of reality, but in the end that’s what you’re doing. If you can square that with your moral system, go ahead.

But I remain agnostic. There are some really good – diabolically good? – studies showing that it works in certain lab situations. There’s a lot of excellent research behind it and a lot of brilliant people giving it their support. But there are also other studies showing that it has no long-term real-world effects that we can measure, and others that might (or might not?) contradict its predictions in other ways. I have only the barest of ideas how to square those facts, and I look forward to hearing from anyone who has more.

I haven’t read Dweck’s book, but it’s an obvious next step for anyone who wants to look into these issues further.