Random Noise Is Our Most Valuable Resource

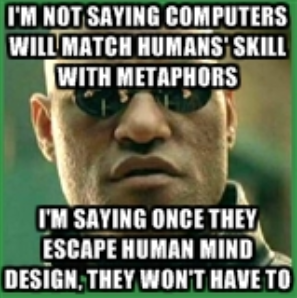

Yesterday I suggested that it will be surprisingly easy to build “creative” computers, because what we think of as “creativity” is just a temporary suppression of our mind’s inbuilt tendency to avoid unusual thoughts that violate its accustomed pattern. A computer could just not have that tendency – or, if that tendency is useful for some reason, it can make it an adjustable parameter that it can relax for “brainstorming” and then turn back up for rigorous thought.

Since we can’t do that, we search for something outside ourselves to break us out of the accustomed patterns. I mentioned how I get a surprising amount of inspiration simply from misunderstanding what other people are saying, and commenters agreed:

Since we can’t do that, we search for something outside ourselves to break us out of the accustomed patterns. I mentioned how I get a surprising amount of inspiration simply from misunderstanding what other people are saying, and commenters agreed:

In partner dancing I sort of stumble onto inventing a lot of new moves by fucking up a standard move. But then it’s kinda hard to remember the new move since it was based on a mistake. The only times I remember a new move is if I make the same mistake at the same point in the step constantly.

Neil Gaiman noted, in his commencement address that’s all over the Internet, that he once misspelled “Caroline” as “Coraline” and he went “that’s interesting,” and saved it for later.

I remember reading that Neuromancer’s great opening line “The sky above the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead channel” was intended just to describe a blue sky, because Gibson’s television showed a blue screen on dead channels, but that most people read it and picture black-and-white static, which makes the line a lot cooler and more memorable

The part where you said you mishear other people, misinterpret it and then have a new idea – shares similarity with Harold Bloom’s ideas about Shakespeare’s soliloquies, wherein the character speaks aloud, mishears himself, misinterprets what he misheard and then allows that new interpretation to change him away from his original stance, allowing growth.

Something else commenters brought up was the idea of deliberately seeking random noise by, for example, rearranging sentences in Markov chains, picking random (tarot) cards, or using “brainstorming strategies” that randomly suggest directions to take something in.

In practice these have never really worked well for me. I think it has to be a very special kind of noise. In fact, as a commenter yesterday pointed out, “noise” may be the wrong word. Maybe “disruption”? Or even “difference”. Something that takes my thoughts processes in a direction different than the ones they would usually go.

This isn’t just about coming up with great works of art or new scientific ideas, it’s about the grunt work of evaluating theories. If I believe A, it probably means I’m in a rut where all the arguments in favor of A are available to me, but all the arguments against A are in some unreachable part of thoughtspace. Just having someone tell them to me might not work – the rut might be so deep that I round them to the nearest cliche or fail to appreciate them correctly. So the goal of looking for “the right kind of noise” is not only to become more creative but to become more correct.

I like this idea of “looking for” the noise. It stands in contradiction to the common conception of creativity as something that happens when you sit down and think really hard. This might work a little, but in general I think of creativity as a resource that needs to be mined somewhere. I don’t expect it to show up by sitting and thinking any more than oil will show up if you sit and think about it. If you’ve done your homework, you can refine your thoughts anywhere, the same way you can refine oil anywhere. But you’ve got to find it first.

Just as geologists know where to look for oil, so there should be some heuristics about where to look for original thoughts that will expand your ideaspace. The main rule seems to be: anywhere with people whose thoughts have diverged from your own a lot.

Cross cultural studies seem like the most fertile source. Eastern philosophy, while not as different from western philosophy as some people like to believe, is still deeply surprising to people who have only learned the Western tradition. My favorite example of someone using foreign cultures to overcome limitations in creativity is Harry Turtledove’s Striking The Balance series. The alien race therein is one of the most convincing and genuinely alien species in all of science fiction. It’s also transparently based on the Chinese Empire. Sitting in an armchair and trying to think of the most shockingly different extraterrestrials you can imagine still gets you something less alien (to American eyes) than simply adopting China for the purpose.

A second example of this: the languages made by beginning conlangers (people who invent constructed languages) are often really laughably bad. I remember one person who just went through an English dictionary, came up with a different word for every word (the = bla, cat = mred, are = nam, on = zig, mat = phlurd) and then combined them with English grammar and syntax (the cats are on the mats = bla mreds nam zig bla phlruds) and thought it was a language. You don’t get any idea how much languages can vary until you study a couple of others. Even then, if you’ve only studied Indo-European languages, the ones you invent – even the ones which in your constructed universe are spoken by creatures of pure energy and meant to be maximally bizarre – still have a clear Indo-European feel to them, because it’s difficult to imagine the dimensions upon which languages can vary until you’ve seen them. As far as I know, no conlanger has ever invented the dual case before they learned it was a real thing. This is another example where someone copying Chinese would get a whole lot weirder than someone trying to sound maximally alien.

But in some cases that can be too foreign, so foreign I can’t understand and integrate it at all. I have always had more luck with the past. I think this is the broader point beyond what I was talking about in Read History Of Philosophy Backwards. The goal of reading old philosophers is to expand your concept-space, realize that ideas you thought were almost tautologically correct actually have strong alternatives it is almost impossible for you to think of on your own. I now realize that part of my failure to understand MacIntyre was because my brain was totally incapable of understanding a certain concept of “community” that was the default in the ancient world. I thought I obviously understood what “community” meant, that there was no other possible meaning, that a lot of people who used it in weird ways were just confused. I was wrong, I never would have figured it out on my own, and eventually being bombarded with past resources helped me figure out things that seemed perfectly obvious to people back then.

Another potent source of intellectual disruption is talking to smart people you disagree with. If they’re smart enough that you know they’re not just making a stupid error, you can be pretty sure their cognitive ruts are different (maybe opposite) to yours. That gives you an exciting opportuntity to explore them and add new areas to your mental terrain. I find that taking the smartest people I can find, believing the most seemingly ridiculous thing, and latching onto them and not shutting up until what they’re saying makes sense to me is just about the quickest way to add new explored areas to my mental map possible. And since they don’t have my ruts, once I have theirs I can be one of the first people to possess two different mental tools at the same time, and then have the ability to synthesize them into exciting new ideas.

The last and most important source of disruption is, of course, reality, which is almost never what you think it is and usually pretty weird.